Visual ergonomics for changing work environments in the COVID-19 pandemic

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought about change in the work environment, increasing remote and hybrid mode of work, presenting a compelling need to study visual ergonomics in this new work environment.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess computer vision symptoms and visual ergonomics in remote and hybrid work settings during the COVID-19 pandemic with a focus on eye to screen relationship.

METHODS:

The computer-vision symptom scale (CVSS17) questionnaire and questions about human factors and ergonomics were included in the survey conducted in September 2021. Sixty-six working professionals (mean age 37 years±5), working from home (n = 44) or in hybrid mode (n = 22) were included in the study. Cramer’s V was used for the correlation coefficient between two categorical variables for assessing eye health in changing work environments.

RESULTS:

Compared to our previous study, the correlation between computer vision syndrome (CVS) symptoms is markedly higher. The population working in hybrid mode experienced eye heaviness with strain to see well (V = 0.6872, p = 0.002) and dryness in the eyes (V = 0.5912, p = 0.0179). The population working from home who are bothered by surrounding lights also report dryness in the eyes (V = 0.3846, p = 0.0005). Screen use hours are higher in work from home situations (43% work more than 9 hrs) than those in hybrid mode of work (4% work more than 9 hrs).

CONCLUSION:

A definite increase in CVS in most of the population working remotely or in hybrid environments is established through this study. User-friendly strategies for raising awareness of applied visual ergonomics can prevent rampant onset of CVS in the working population.

1Introduction

The entire world was on the verge of becoming digital and the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has made that even more relevant in a short span of time [1]. During the pandemic, digital work for each individual has grown in the work from home (WFH) setups. Many offices offer hybrid work environments that involve a new set of challenges from usability and visual ergonomics perspectives. A glaring side effect of this new work culture is eye strain due to high amount of screen-based work. Computer vision syndrome (CVS) is recognized by the American Optometric Association as a group of vision and eye problems due to excessive computer use [2]. It is also found that when the visual demand is higher than a person’s visual ability, CVS and digital eye strain (DES) occur [3].

It is seen that the population whose work is computer dependent reports more vision problems. The occurrence of CVS ranges from 64% to 90% for computer users. Globally around 60 million people are affected by CVS [4]. It has been reported that visual symptoms are prevalent in 75% to 90% of computer workers in India [5].

This study is an attempt to further previous research [6], which investigated the relationship between the increase of digital work in the pandemic and related digital eye strain. The study shows other significant changes in the digital work environments through parameters of number of hours spent on digital work, onset of hybrid work culture and its effect on eye health. The aim of the study is to examine CVS and visual ergonomics in remote and hybrid settings.

2Materials and methods

An online questionnaire was designed and administered (Appendix) in September 2021. The survey consisted of the computer-vision symptom scale (CVSS17) questionnaire [7] modified to additionally include Ergonomics and Human Factors (E/HF)-related questions. A random sampling method was used for collecting the data representative of working professionals in the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 66 working professionals participated in the survey voluntarily via Google Forms. The inclusion criteria for the surveyed population were professionals working digitally during the COVID-19 pandemic and continued to do so until the survey was conducted. The Google Forms questionnaire was circulated through social media in various professional circles and responses were collected; no database of professionals was used to conduct the survey. Only the forms that were filled in completely were included for further analysis. Demographic measures only included the respondents’ gender and age.

The questionnaire includes three sections: the first section includes eye health overview-related questions, the second section consists of eye-related symptoms faced during 4 weeks prior to taking the survey using the CVSS 17 tool and the third section included work-related aspects of visual ergonomics/design, computer activities and the surrounding environment.

2.1Eye health overview

In this section of the questionnaire, information was gathered about the status of eye examination of the respondents and their use of corrective eyewear during working hours.

2.2Eye-related symptoms

Eye symptoms of eye pain, frequent blinking, eye burning, squinting, eye stinging and eye heaviness were considered. These symptoms faced by the participants were categorized into never (not experienced by the participant), rarely (persists for a few minutes to hours), frequently (stays for a few hours and subsides after taking a rest) and constantly (persists even after taking breaks/rest). Eye symptoms of blurred letters on screen, strain to see well, letters appear double, watery eyes and red eyes were considered and were categorized into never, very little, little, moderate amount, often and very often. Eye symptoms experienced after digital work including heavy eyes, strain to see well, dryness of the eyes and problems by exposure to light were also considered and categorized into strongly disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree and strongly agree. The symptoms were analyzed for the overall population as well as for the population engaging in WFH and hybrid work setups.

2.3Visual ergonomics, human factors, computer activities and surrounding environments

In this section of the questionnaire, questions about visual ergonomics and human factors were asked to enquire about various interactions concerning the digital screen and eye to screen relationships of the participants. Parameters studied were size of the screen, type of device used for work, eye to screen angle and distance, font size, awareness of glare on the screen, resolution of the screen, use of blue/warm screen setting, awareness and use of refresh rate, primary mode of work, hours spent in front of the screen and breaks taken.

The data was analyzed using standard statistical tests. All descriptive data was presented as a percentage. The categorical variables were analyzed using Cramer’s V for the correlation coefficient between two categorical variables.

This study attempts to show the increased impact of the new work environment on eye health through the perspective of the above three lenses of basic eye health overview. The CVSS 17 tool for eye-related symptoms was used along with ergonomics and human factors to understand the interactions of the participants within the eye to screen environment. Environmental factors like illumination level, ambient light, lumens and glare were not considered as in the global pandemic the work setups are not under control of the digital worker. The only aspect that stays consistent is the eye to screen relationship.

3Results

A total of 66 professionals working during the COVID-19 pandemic responded to our survey circulated online in September 2021. The mean age of the respondents was 37 years (SD = 5 years); among them 44 (66.5%) respondents were male and 22 (33.5%) were female.

Forty-four participants were working from home out of which 17 (38%) were female and 27 (61%) were male. Fourteen respondents indicated working in hybrid mode and eight indicated working from the office. The working from the office population was merged with the population in hybrid mode, as they were also working from home after office hours. Thus, a total of 22 respondents were considered to be working in hybrid mode. Among the 22 respondents working in hybrid mode 5 (23%) were females and 17 (77%) were males.

3.1Change in working hours

The study shows that screen time (hours spent in front of the screen) is higher in WFH situations than in hybrid mode of work. It was also found that 43% of the population working from home spent more than 9 hours in front of the screens compared with the 4% of population working in hybrid mode (Table 1).

Table 1

Hours spent in front of the screen per day in work from home and hybrid mode of work

| Work from home | Hybrid work | |

| Less than 1 hour | 1 (2%) | 3 (13%) |

| 1 to 5 hours | 5 (11%) | 10 (45%) |

| 6 to 9 hours | 19 (43%) | 8 (36%) |

| More than 9 hours | 19 (43%) | 1 (4%) |

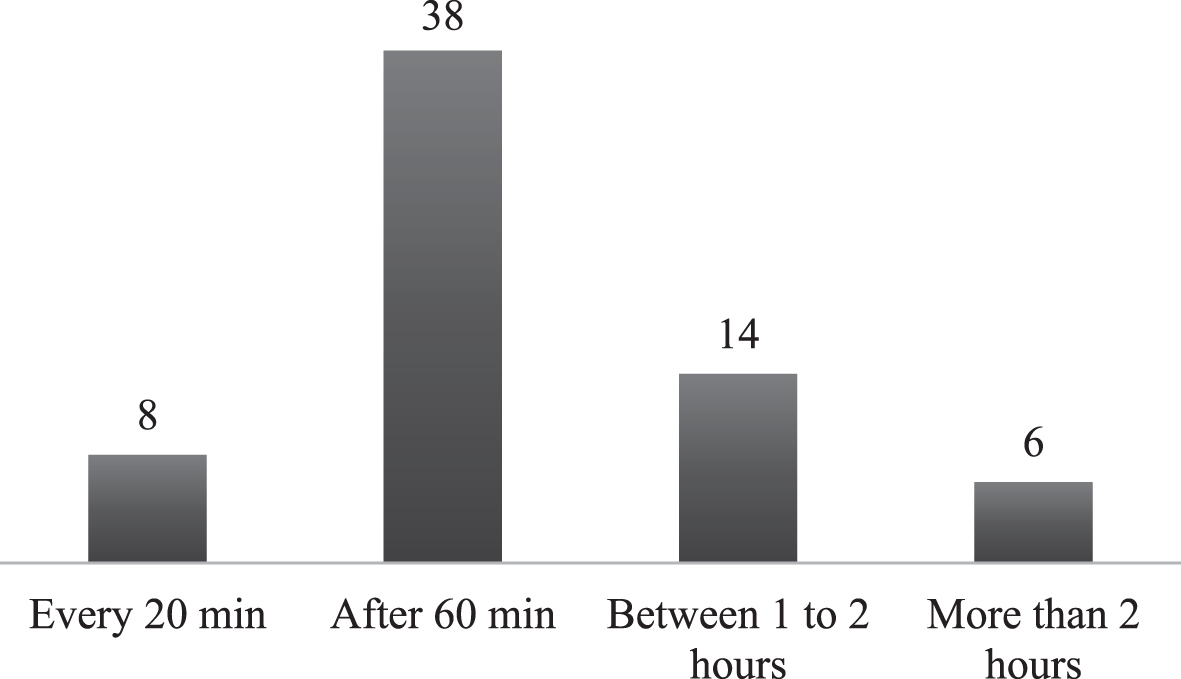

Overall, 56% of the participants prefer to take a break after 60 min of working. Also, only 10.5% of the participants take a break after 20 minutes, which is the recommended standard [8] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Frequency of breaks while working on a computer (n = 66).

3.2Mobile use for work during pandemic

Our study confirms that a significant population uses mobile screens for work-related activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. 64% of the population uses mobile phones for work to email, read articles, have video call meetings, read for research activities and for client engagement.

3.3Eye symptoms

In comparison to our previous study [6], the correlation between CVS symptoms is markedly higher. Overall participants experiencing eye burning also experience dry eyes (V = 0.4108, p = 0.0001). The people whose eyes become heavy during work also face stinging in the eyes (V = 0.4578, p = 0.0001). The screen becomes blurry for the people who report eye sting (V = 0.4333, p = 0.0017). The population that is bothered by surrounding lights after digital work also experience strain to see well (V = 0.3858, p = 0.0005) (Table 2).

Table 2

Computer vision symptoms (n = 66)

| Never | Rarely | Frequently | Constantly | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Did your eyes hurt? | 18 | 27.27 | 33 | 50.00 | 11 | 16.67 | 4 | 6.06 | ||||

| Did you have to blink more than usual? | 18 | 27.27 | 28 | 42.42 | 19 | 28.79 | 1 | 1.52 | ||||

| Did your eyes burn? | 24 | 36.36 | 28 | 42.42 | 12 | 18.18 | 2 | 3.03 | ||||

| Did you feel like you were crossing your eyes (squinting)? | 39 | 59.09 | 17 | 25.76 | 7 | 10.61 | 3 | 4.55 | ||||

| Did your eyes sting? | 43 | 65.15 | 19 | 28.79 | 4 | 6.06 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Did your eyes become heavy? | 15 | 22.73 | 25 | 37.88 | 23 | 34.85 | 3 | 4.55 | ||||

| Never | Very little | Little | Moderate | Often | Very often | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Did the letters appear blurry? | 37 | 56.06 | 14 | 21.21 | 10 | 15.15 | 3 | 4.55 | 2 | 3.03 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did you strain to see well? | 20 | 30.30 | 14 | 21.21 | 12 | 18.18 | 12 | 18.18 | 3 | 4.55 | 5 | 7.58 |

| Did the letters appear double? | 50 | 75.76 | 7 | 10.61 | 4 | 6.06 | 5 | 7.58 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did you experience watery eyes? | 21 | 31.82 | 19 | 28.79 | 14 | 21.21 | 6 | 9.09 | 6 | 9.09 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did you experience eye redness? | 33 | 50.00 | 12 | 18.18 | 13 | 19.70 | 6 | 9.09 | 2 | 3.03 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Strongly disagree | Slightly disagree | Slightly agree | Strongly agree | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Eyes became heavy | 7 | 10.61 | 11 | 16.67 | 35 | 53.03 | 13 | 19.70 | ||||

| Strain to see well | 19 | 28.79 | 12 | 18.18 | 27 | 40.91 | 8 | 12.12 | ||||

| Dry eyes | 14 | 21.21 | 14 | 21.21 | 22 | 33.33 | 16 | 24.24 | ||||

| Bothered by light | 22 | 33.33 | 10 | 15.15 | 28 | 42.42 | 6 | 9.09 | ||||

The population working in hybrid mode experienced eye heaviness with strain to see well (V = 0.6872, p = 0.002) and dryness in the eyes (V = 0.5912, p = 0.0179). People working from home experience strain to see well with eye heaviness (V = 0.4982, p = 0.0051) and dryness in the eyes (V = 0.4366, p = 0.0479). The population working from home who are bothered by surrounding lights also experience dryness in the eyes (V = 0.3846, p = 0.0005).

After analyzing the data in Tables 3 & 4, the following inferences are drawn. In the hybrid work mode, no one reported experiencing eye symptoms of eye pain, squinting of eyes, excessive blinking, burning of eyes and heaviness of eyes on a constant basis in comparison to WFH population. Eye symptoms of letters becoming blurry, straining to see well, letters appearing double, watery eyes and redness of eyes are reported to be less in the hybrid working population than in the WFH population. After digital work, the symptoms of heaviness of eyes and strain to see well show a higher trend in the WFH population than hybrid population. The population that strongly agrees as experiencing dry eyes is greater in hybrid population (40.90%) than in the WFH population (15.91%).

Table 3

Computer vision symptoms for the work from home population (n = 44)

| Parameter | Never | Rarely | Frequently | Constantly | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Did your eyes hurt? | 14 | 31.82 | 19 | 43.18 | 7 | 15.91 | 4 | 9.09 | |||||

| Did you have to blink more than usual? | 14 | 31.82 | 15 | 34.09 | 14 | 31.82 | 1 | 2.27 | |||||

| Did your eyes burn? | 19 | 43.18 | 14 | 31.82 | 9 | 20.45 | 2 | 4.55 | |||||

| Did you feel like you were crossing your eyes (squinting)? | 28 | 63.64 | 9 | 20.45 | 4 | 9.09 | 3 | 6.82 | |||||

| Did your eyes sting? | 28 | 63.64 | 12 | 27.27 | 4 | 9.09 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Did your eyes become heavy? | 9 | 20.45 | 15 | 34.09 | 17 | 38.64 | 3 | 6.82 | |||||

| Parameter | Never | Very little | Little | Moderate | Often | Very often | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Did the letters become blurry? | 27 | 61.36 | 7 | 15.91 | 5 | 11.36 | 3 | 6.82 | 2 | 4.55 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Did you strain to see well? | 16 | 36.36 | 8 | 18.18 | 4 | 9.09 | 8 | 18.18 | 3 | 6.82 | 5 | 11.36 | |

| Did the letters appear double? | 31 | 70.45 | 6 | 13.64 | 2 | 4.55 | 5 | 11.36 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Did you experience watery eyes? | 17 | 38.64 | 8 | 18.18 | 9 | 20.45 | 5 | 11.36 | 5 | 11.36 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Did you experience eye redness? | 22 | 50.00 | 8 | 18.18 | 6 | 13.64 | 6 | 13.64 | 2 | 4.55 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| After digital work | Strongly disagree | Slightly disagree | Slightly agree | Strongly agree | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Eyes became heavy | 6 | 13.64 | 6 | 13.64 | 22 | 50.00 | 10 | 22.73 | |||||

| Strain to see well | 14 | 31.82 | 7 | 15.91 | 17 | 38.64 | 6 | 13.64 | |||||

| Dry eyes | 11 | 25.00 | 10 | 22.73 | 16 | 36.36 | 7 | 15.91 | |||||

| Bothered by light | 17 | 38.64 | 5 | 11.36 | 18 | 40.91 | 4 | 9.09 | |||||

Table 4

Computer vision syndrome for hybrid mode of work (n = 22)

| Parameter | Never | Rarely | Frequently | Constantly | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Did your eyes hurt? | 4 | 18.18 | 14 | 63.64 | 4 | 18.18 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Did you have to blink more than usual? | 4 | 18.18 | 13 | 59.09 | 5 | 22.73 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Did your eyes burn? | 5 | 22.73 | 14 | 63.64 | 3 | 13.64 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Did you feel like you were crossing your eyes (squinting)? | 11 | 50.00 | 8 | 36.36 | 3 | 13.64 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Did your eyes sting? | 15 | 68.18 | 7 | 31.82 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Did your eyes become heavy? | 6 | 27.27 | 10 | 45.45 | 6 | 27.27 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Parameter | Never | Very little | Little | Moderate | Often | Very often | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Did the letters become blurry? | 10 | 45.45 | 7 | 31.82 | 5 | 22.73 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did you strain to see well? | 4 | 18.18 | 6 | 27.27 | 8 | 36.36 | 4 | 18.18 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did the letters appear double? | 19 | 86.36 | 1 | 4.55 | 2 | 9.09 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did you experience watery eyes? | 4 | 18.18 | 11 | 50.00 | 5 | 22.73 | 1 | 4.55 | 1 | 4.55 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did you experience eye redness? | 11 | 50.00 | 4 | 18.18 | 7 | 31.82 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| After digital work | Strongly disagree | Slightly disagree | Slightly agree | Strongly agree | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Eyes became heavy | 1 | 4.55 | 5 | 22.73 | 13 | 59.09 | 3 | 13.64 | ||||

| Strain to see well | 5 | 22.73 | 5 | 22.73 | 10 | 45.45 | 2 | 9.09 | ||||

| Dry eyes | 3 | 13.64 | 4 | 18.18 | 6 | 27.27 | 9 | 40.91 | ||||

| Bothered by light | 5 | 22.73 | 5 | 22.73 | 10 | 45.45 | 2 | 9.09 | ||||

3.4Visual ergonomics

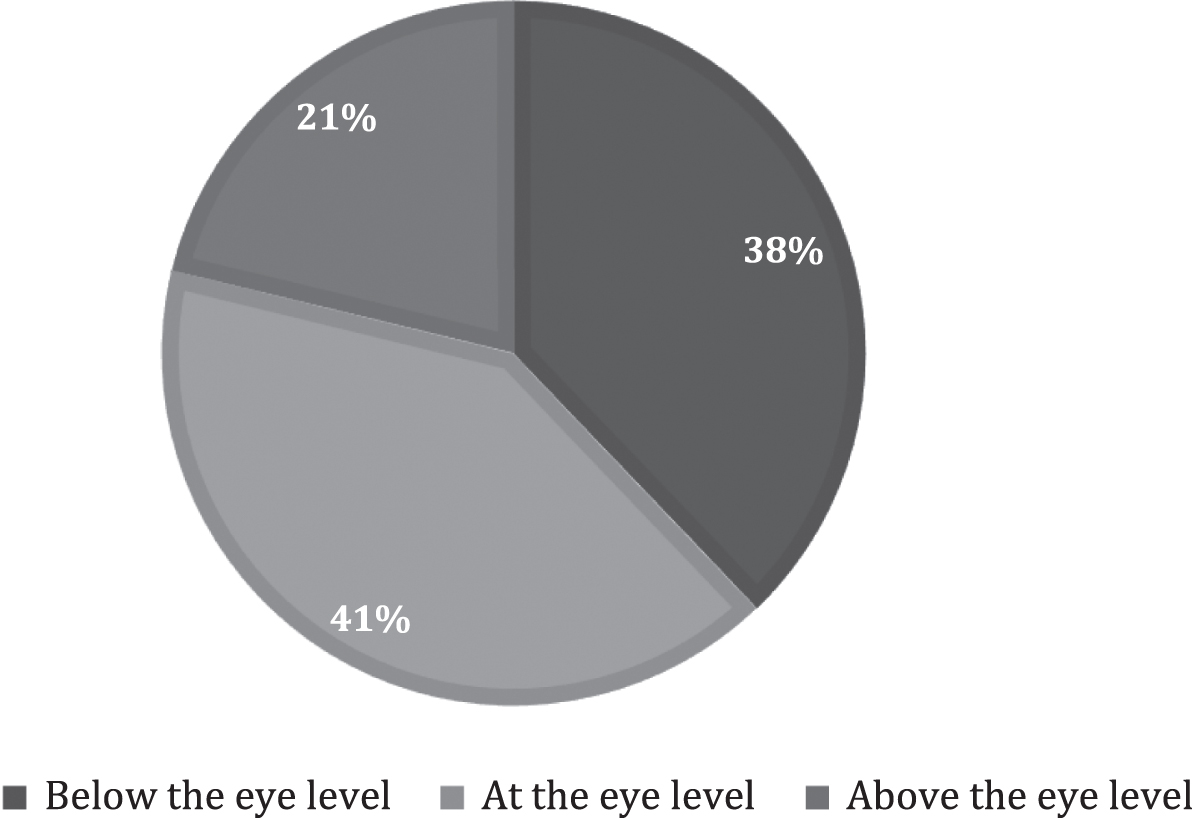

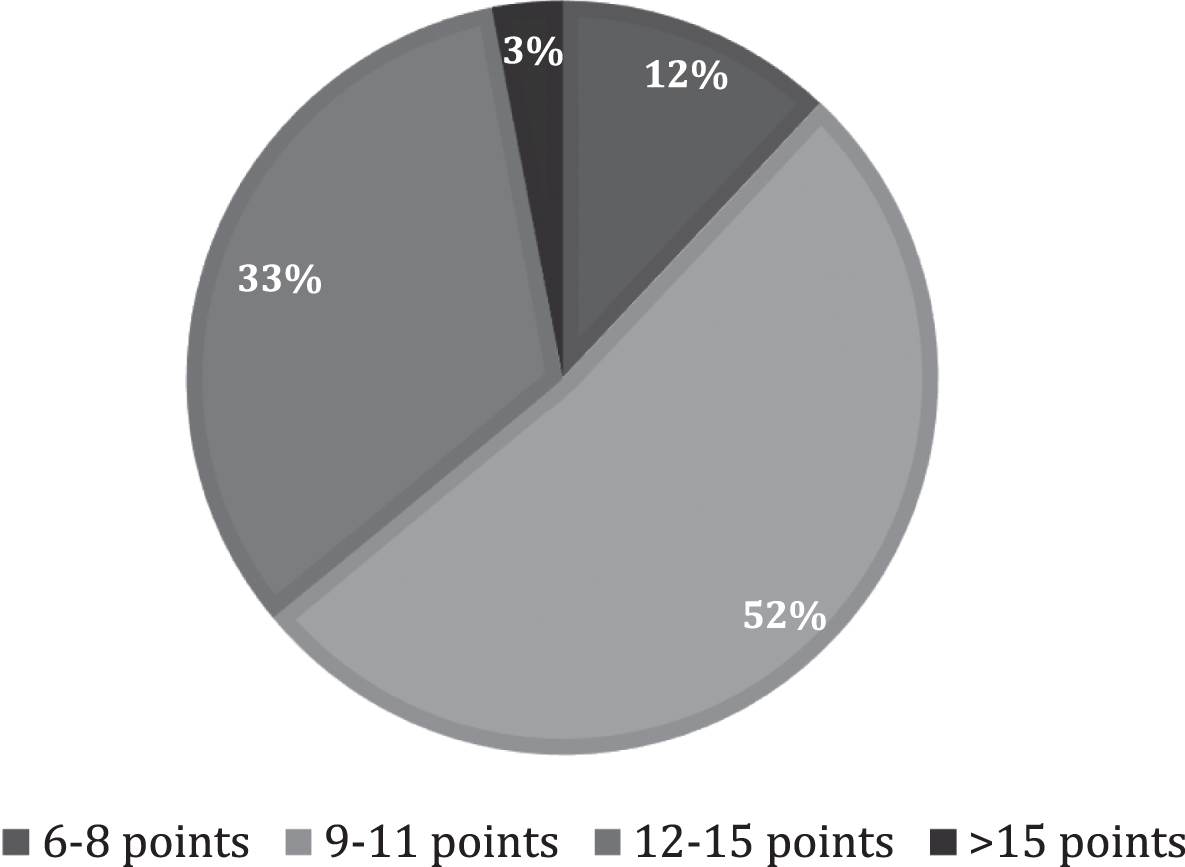

An important aspect of visual ergonomics studied was the relative position of the top of the computer screen and eye level. In the population studied, 37% had the screen below the eye level, 21% above the eye level and 40% at the eye level (Fig. 2). Another crucial factor studied was the font size used by the working population while working on the screens. 52% use 9–11 font size, 33% use 12–15 font size, 12% use 6–8 font size and 3% use larger than 15 points font size (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2

Relation between top of the computer screen to eye level.

Fig. 3

Use of font size (percentage).

4Discussion

A combination of eye and visual issues occur with increased visual demands that show presence of CVS. The working population globally had to shift to working on computers from their homes with minimally optimal conditions for work. They also experienced 1.5 hours more working hours in the working from home scenario during the pandemic compared with the pre-pandemic working from office scenario [9]. This has put the working professionals in a high-risk zone for CVS [3]. A sizable population of working professionals studied during the pandemic have reported eye strain, which acts as an indicator for onset of further problems like blurry vision or similar visual difficulties [6]. The results of this study suggest that the individuals reporting eye strain also reported the blurring of screen after continuous screen use.

Research into device usage reveals that laptops are most prominently used in home- office environments, followed by desktop and tablets. Mobile phones have been predominantly used for work as well [10]. Equivalent results have been found in our study where the use of mobile phones for work is seen to be 64% among the working professionals surveyed.

As stated by Reddy et al., working professionals with their computer screens set below the eye level had significantly lower CVS symptoms than those that viewed the screen at or above the eye level [11]. In the current study 61% of the respondents used a screen at or above the eye level. Also, the font size used by 52% of the respondents was between the 9–11 point which is much lower than the recommended 14 point for maintaining good visual ergonomic conditions [12]. In view of the above observations, there is an obvious need to create more awareness about visual ergonomics practices.

The current study results reveal that hours spent in front of the screen for work are higher in WFH situations than in hybrid mode of work. Comparable results of increased work hours in WFH situation were also noted by Awada et al. [9].

Burning sensation of the eyes, eye pain, dryness of the eyes, increased light sensitivity were the most common symptoms due to prolonged use of digital devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar reporting was done by Almarzouki et al. [5].

As a consequence of the pandemic, WFH and hybrid work cultures have taken root and have resulted in poor working environments. This can affect the eye health of the professionals working on screens and affect their productivity at work [13]. Unclean computer screens, defective or bad-quality computer screens and higher viewing angle are commonly found issues in working conditions which can result in blurred and unclear images [14]. The absence of ideal ergonomic conditions for work at home offices is due to a lack of awareness as the users are not professionals that understand the spatial factors involved in applied visual ergonomics to the ideal workspace. As most working professionals are now moving to a hybrid work culture, understanding visual ergonomics with ease and its implementation will be essential for the eye to screen visual interaction.

4.1Limitation and future work

This study was not without limitations. Workspaces and their physical parameters were different for all working professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic so this was not taken into consideration in this study. We also found that not enough research is done to study the challenges encountered due to the uncontrolled environmental variables pertaining to the relationship of eye to screen. Further research to control the immediate eye to screen relationship needs to be designed, as home or hybrid work environments cannot match more controlled traditional office setups. The study was done on a random population of working professionals and is thus only indicative of deeper issues of visual ergonomics and human factors.

Further research is needed to understand opportunities in human computer interaction to facilitate user friendly regulation of eye to screen relationship to prevent CVS. Applicable strategies for its implementation need to be proposed and assessed with urgency before the prevalence of CVS becomes a global issue. Furthermore, in relation to eye health, use of glasses/contact lenses during the use of digital devices and binocular vision conditions needs to be investigated to understand the consequences on overall CVS symptoms.

5Conclusion

A definite onset of CVS is reconfirmed by this study. The number of hours spent in front of a screen is higher in the population working from home than those in hybrid work culture. Structured research is needed to better understand the human computer interaction challenges faced in the eye to screen relationship, especially in the new working environments. Working towards the prevention of CVS through easy to implement strategies is needed. User friendly strategies of applied visual ergonomics in the eye to screen space, raising awareness about visual ergonomics in computer users and good eye care can prevent rampant onset of CVS in the working population.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Dr. Vishwanath Karad MIT World Peace University and/or national research committee with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no acknowledgments.

Funding

The authors report no funding.

Supplementary materials

The appendix is available from https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-211130.

References

[1] | Sheppard AL , Wolffsohn JS . Digital eye strain: Prevalence, measurement and amelioration. BMJ open Ophthalmol. (2018) ;3: (1):e000146-e000146. |

[2] | Zainuddin H , Isa MM . Effect of human and technology interaction: Computer vision syndrome among administrative staff in a public university. Int J Busin Humanit Technol. (2014) ;4: (3):38–44. |

[3] | Rosenfield M . Computer vision syndrome: A review of ocular causes and potential treatments. Ophthal Physiol Optics. (2011) ;31: (5):502–15. |

[4] | Almarzouki N , Faisal K , Nassief A , Najem N , Eid R , Albakri R , Alhibshi D , Alwethinani S , Ashi H . Digital eye strain during COVID-19 lockdown in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Contemp Med Sci. (2021) ;7: (1):40–5. |

[5] | Logaraj M , Priya VM , Seetharaman N , Hedge SK . Practice of Ergonomic Principles and computer vision syndrome (CVS) among under graduates students in Chennai. National Journal of Medical Research. (2013) ;3: (2):111–6. |

[6] | Dabir N , Khanwalkar P . Applied Visual Ergonomics- A Compelling Consideration for the New Normal. In Proceedings of the Congress of the International Ergonomics Association. Springer, Cham, (2021) , pp. 723–8. |

[7] | González-Pérez M , Susi R , Antona B , Barrio A , González E . The computer-vision symptom scale (CVSS17): Development and initial validation. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. (2014) ;55: (7):4504–11. |

[8] | Randolph SA . Computer vision syndrome. Workplace Health & Safety. (2017) ;65: (7):328. |

[9] | Awada M , Lucas G , Becerik-Gerber B , Roll S . Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on office worker productivity and work experience. Work. (2021) ;20: (Preprint):1–9. |

[10] | Gerding T , Syck M , Daniel D , Naylor J , Kotowski SE , Gillespie GL , Freeman AM , Huston TR , Davis KG . An assessment of ergonomic issues in the home offices of university employees sent home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. (2021) ;68: (4):981–92. |

[11] | Reddy SC , Low CK , Lim YP , Low LL , Mardina F , Nursaleha MP . Computer vision syndrome: A study of knowledge and practices in university students. Nepalese Journal of Ophthalmology. (2013) ;5: (2):161–8. |

[12] | Banerjee J , Bhattacharyya M . Selection of the optimum font type and size interface for on screen continuous reading by young adults: An ergonomic approach. J Hum Ergol (Tokyo). (2011) ;40: (1-2):47–62. |

[13] | Richter HO , Sundin S , Long J . Visually deficient working conditions and reduced work performance in office workers: Is it mediated by visual discomfort? International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. (2019) ;72: :128–36. |

[14] | Anshel J . Computer vision syndrome causes and cures. Managing Office Technology. (1997) ;42: (7):17–9. |