Abstract

In recent years, the centres of Polish cities were subject to intensive urban regeneration processes. This was due to the availability of European Union funds (since 2004), which made it possible to finance projects curbing the degradation of urban areas. Since 2015 the Polish Urban Regeneration Act has structured the urban renewal programming process and has created new legal tools that facilitate public intervention in the most neglected areas. At the same time, gentrification processes have occurred in many Polish cities, either in conjunction with or as a result of urban regeneration. While urban regeneration is usually met with a positive response from city inhabitants, gentrification causes conflicts which are difficult to resolve. The aim of this paper is to analyse and assess the social manifestations of urban renewal and gentrification processes in deprived areas using the city of Poznań (Poland) as an example. Activities initiated by Poznań’s local authorities are considered to be exemplary in Poland and as a result, they are imitated by numerous other cities. The paper presents the results of an analysis of changes that took place in the years 2006–2019 in the city centre that developed a municipal regeneration program. The transformations identified include an increase in property prices and rents and above all, a dramatic transformation of the social structure. The spatial consequences of these changes include the improved condition of residential and public buildings, restoration of green areas and modernisation of other public spaces. The paper attempts to assess which of the two processes, urban regeneration or gentrification, is the principal driving force behind the changes mentioned above.

Introduction

At present, the regeneration of deprived urban areas is considered to be one of the key principles of urban policy in Poland. This stems from the growing awareness among local authorities, inhabitants, activists and entrepreneurs of the importance of both the responsible shaping of urban spaces and addressing the existing social problems present in neglected urban districts. Another important aspect is funding for regeneration programs from the European Union regional and national operational programs in Poland and other Central and Eastern European countries, available after their accession to the EU in 2004 (Hlaváček et al., 2016; Swianiewicz et al., 2011; Ciesiółka, 2018).

In this article, urban regeneration is construed in accordance with the definition proposed by Roberts (2010: 17) as the comprehensive and integrated vision and action which leads to the resolution of urban problems and which seeks to bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental condition of an area that has been subject to change. To a great extent, this definition conforms to the one used in the Polish Urban Regeneration Act where regeneration is defined as the process of resolving crisis situations in deprived areas, performed in a comprehensive manner, involving integrated actions for the benefit of local communities, space and economy, which focuses on a given territory and is conducted by interested parties in accordance with the Municipal Regeneration Program document (see Ciesiółka, 2018; Jarczewski and Dej, 2015; Parysek, 2008). It is worth noting that as in other Central and Eastern European countries, in Poland it is the local authorities who decide on the directions and pace of urban regeneration activities and invite other actors to participate. Undoubtedly, the urban regeneration projects that are implemented lead to spatial as well as social and economic changes (Jarczewski and Kułaczkowska, 2019). Private investors also take part in activities in deprived areas. Their investments help speed up the development of problem areas, although they are also intended to bring financial benefit to the developers.

In 2015, the Polish Urban Regeneration Act was adopted. This is the first legal regulation regarding urban renewal. The concept of regeneration was defined in it and the principles of creating, implementing and monitoring regeneration programs were introduced. An important role was entrusted to public participation in the regeneration process. Unfortunately, due to excessive costs, it does not provide a system to protect the inhabitants of regenerated areas, which has been expected since the beginning of urban regeneration initiatives in Poland. This is considered the most important drawback of Polish legal solutions in the field of regeneration (Szlachetko and Borówka, 2017). As a result, social exchange, already triggered by the first regeneration projects in late 2010, even accelerated after the entry into force of the Act on regeneration. In consequence, urban regeneration and gentrification processes became intertwined.

In this paper, we understand gentrification as a process involving a change in the population of land‐users such that the new users are of a higher socio-economic status than the previous users, together with an associated change in the built environment through a reinvestment in fixed capital (Clark, 2005: 263). What distinguishes present-day gentrification from other processes that shape the spatial structure of inner cities is a possible direct or indirect displacement of lower-income residents by wealthier groups (Davidson and Lees, 2005). It is the specific process of invasion-succession, which assumes a rise in the social and material status of urban areas (Wyly et al., 2010). Gentrification causes positive spatial changes and, at the same time, may result in community displacement. The ultimate effects of such displacement are less clear (Florida, 2015). However, it should be mentioned that some studies do not see resettlement as being an integral part of gentrification (Levy et al., 2007). It becomes a possible negative consequence of that process, but not a component of it. On the other hand, there are many strategies and tools for controlling gentrification‐induced displacement, such as public intervention and political will; community participation and bottom‐up planning processes; embedded local community and community solidarity; community movements and political activism; public/private/community partnership and having multiple financial resources (Ghaffari et al., 2018). Gentrification does not always necessarily mean uncoordinated displacement, especially when it has been initiated by regeneration.

In recent years, the gentrification process has become particularly important for researchers from Central and Eastern Europe because of the increasing social and economic inequalities and the liberalisation of the real estate market after the socialism period, which had a considerable impact on the regeneration of towns and cities (Wiest, 2012). Studies devoted to the gentrification process were conducted in Prague (Sykora, 1996; 2005), Budapest (Kovács, 1998; Kovacs et al., 2013), Tallinn (Feldman, 2000; Kährik, 2006), Bucharest (Chelcea, 2006), Moscow (Badyina and Golubchikov, 2005; Golubchikov and Badyina, 2006), Warsaw (Górczyńska, 2017; Dudek-Mańkowska and Iwańczak, 2018) and other cities. It should be noted, however, that many researchers studying gentrification in post-socialist cities are critical of copying solutions based on British and American experiences (Kovács, 1998; Bernt, 2016). Gentrification in Central and Eastern Europe is at a much earlier stage than in Western Europe or in the United States, where a process of secondary gentrification of districts that have already been subject to gentrification occurs (Lees et al., 2013). Additionally, it usually applies to much smaller areas, often located in city centres (Jakóbczyk-Gryszkiewicz et al., 2017; Bernt et al., 2015). Furthermore, gentrification is strongly connected with the reprivatisation of real estate confiscated by socialist state authorities after the Second World War and returned to its original owners after 1990 (Jakóbczyk-Gryszkiewicz et al., 2017).

Another important factor is the attempt to fill in the gaps between existing buildings in the city centres. These plots remained unused during the socialist period and after the political transformation became subject to speculation and later to intensive development (Kusiak, 2017; Kowalewski et al., 2018). As a result, developers investing in urban regeneration areas are viewed as initiators of gentrification in Central and Eastern Europe (and in Poland) much more often than in Western Europe and the United States (Badyina and Golubchikov, 2005). What is more, they even use terms like “urban regeneration” or “urban renaissance” as euphemisms for gentrification (Maloutas, 2011). The relations between regeneration and gentrification have been studied for many years (for example, Auger, 1979; Borgegard and Murdie 1993; Badcock, 1995; Haase et al., 2012). However, there is still a lack of research exploring the relationships between these processes in Central and Eastern Europe in full.

The aim of this paper is to analyse and evaluate the relations between urban regeneration conducted by local authorities and the gentrification process in Poland with particular emphasis on displacement, using the city of Poznań as an example. The selection of Poznań for our case study was influenced by several factors. Urban regeneration activities have been underway in Poznań for a long time: the first program was created in 2006 and was one of its kind in Poland. All activities were undertaken consistently in the same districts, mostly in the city centre (Śródmieście), and thus are now at a very advanced stage. Using their experience, the local authorities in Poznań initiated changes in the proposed urban regeneration legislation (however, not all of their suggestions were included in the 2015 Act). As a result, Poznań is considered a precursor of urban regeneration in Poland (Ciesiółka, 2014). Additionally, attempts have already been made to analyse the connection between urban regeneration and gentrification in Poznań (Bardzińska-Bonenberg, 2012; Ciesiółka, 2010; Dolata, 2012; Jachowska, 2016; Nowak, 2013; Kaźmierczak et al., 2011). However, these studies focused on small parts of regenerated areas and mostly examined spatial changes.

The paper is divided into the following sections. First, we describe urban regeneration programs and activities in Poznań in the years 2006–2017. Following an outline of our research methods, our analysis then focuses on the social as well as the economic and spatial aspects of these regeneration activities. Most often, Poznań’s local authorities were the initiator of these activities, which were accompanied by growing private sector interest in the regenerated areas. These representatives of the private sector mostly involved developers, who are the biggest contributor to the Polish construction market. We also formulate predictions regarding future changes in Poznań’s regenerated areas. To do so, we used the results of a social study comprising 200 questionnaire interviews conducted with the inhabitants of the regenerated areas and 9 in-depth interviews with individuals involved in the urban regeneration and gentrification processes. Finally, the paper is summarized with conclusions which present the major relationships between urban regeneration and gentrification observed in Poznań in the course of the study.

Regeneration programs and initiatives in Poznań in the years 2006–2017

Urban regeneration in Poznań started in 2005, when the Urban Regeneration Department was set up at the City Hall. Its task was to coordinate work on the regeneration program and regeneration projects. One of the key reasons for commencing urban regeneration works, apart from the existing social, economic and spatial problems in the city, was the financing from EU funds that became available after accession of Poland to the European Union in 2004.

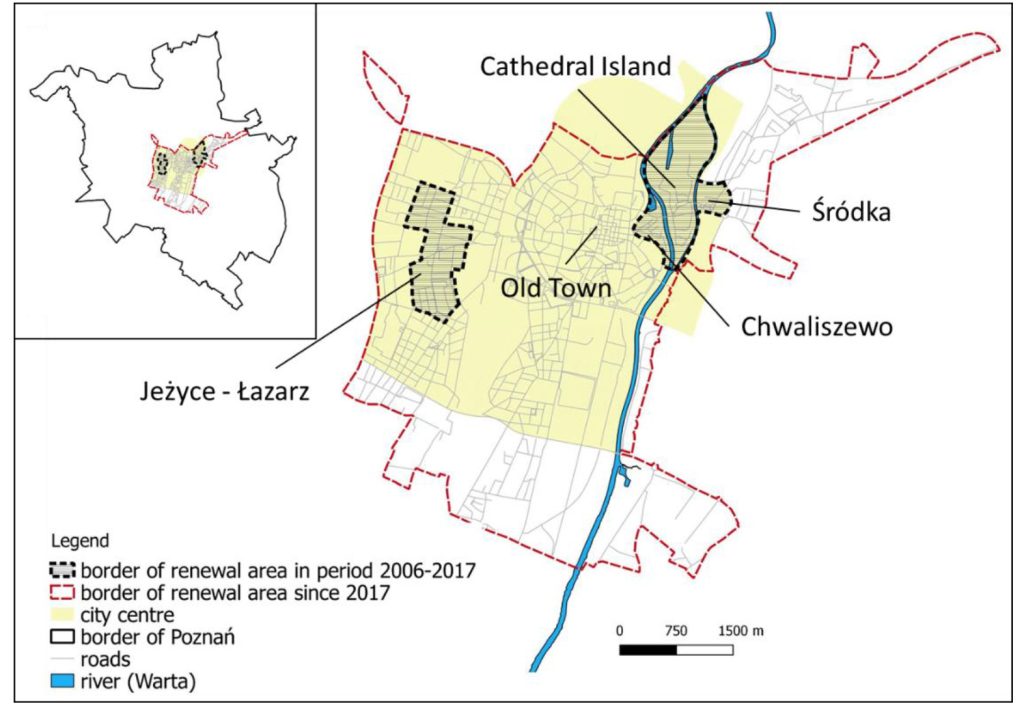

Since 2006, six urban regeneration programs have been developed in Poznań. Usually, new documents called for the continuation of activities listed in preceding programs. This was the result of implementing the concept of ongoing regeneration, with gradual changes over many years. All districts in the city centre (Śródmieście) were considered deprived but it was decided that at first action would be taken in pilot areas on the outskirts of the city centre, firstly in Śródka, followed by Cathedral Island (Ostrów Tumski), Chwaliszewo, Jeżyce and Łazarz districts. However, the total area was still small, inhabited by 10,450 people, which amounts to about two per cent of the city population. Importantly, areas subject to regeneration are located along major streets important for supporting the development of the city centre, as well as along the main tourist route running through the centre of Poznań. The purpose of the actions prescribed in the regeneration programs was: to develop the spatial, historical, cultural and symbolic features of districts in the city centre; to prevent further degradation and devaluation of space and building fabric; to improve considerably the life situation, employment conditions and living conditions of local community members; to prevent social exclusion, marginalisation and segregation; to create conditions for sustainable development of commerce and services, favouring the creation of new jobs; and to improve public transport and environmental conditions.

In 2010, a regeneration program was approved for the renewal of post-industrial and post-military areas scattered throughout the city, as well as those located outside the city centre. Activities conducted over the following years focused on four areas:

- Activation and integration of urban communities: in Śródka, Chwaliszewo and Jeżyce, these included organising periodical cultural events, including concerts, theatre performances, multimedia shows, exhibitions and social events such as Neighbour Day, local fairs, celebrations of bridge or street day.

- Small improvements: mainly in Jeżyce and Chwaliszewo, these included repairs to streets and sidewalks, cleaning up public spaces, creating small green areas, introducing street furniture.

- Public investments: in Śródka, Chwaliszewo and Cathedral Island, including the rebuilding of a bridge to increase access to the areas, the building of the Interactive Cathedral Island History Centre, a museum devoted to the earliest history of Poland, creating an Archaeological Reserve, creating the Nowa Gazownia (New Gas-works) Cultural Centre and an urban beach along the banks of the Warta river.

- Refurbishment of communal flats: mainly in Łazarz and to a limited degree in Śródka.

The activities conducted by public authorities were accompanied by increasing private investments. These mainly included the refurbishment of privately-owned tenement buildings and construction of new residential buildings as well as banks, restaurants and cafes in new buildings erected in unused spaces between existing buildings.

A breakthrough in the approach to urban regeneration in Poznań occurred in 2015, when the new Urban Regeneration Act came into force and its tenets had to be implemented. This allowed much greater areas of the city to be incorporated into regeneration activities – up to 20 per cent of the city area and up to 30 per cent of its inhabitants. As a result, in 2017 a new urban regeneration program was adopted which covers almost the entire city centre (see Figure 1).

Moreover, the scope of planned public activities is much greater and involves large-scale investment projects related to the renovation of major streets, construction of a new tram route, construction of new pedestrian bridges across the Warta River, construction of community centres in housing estates and many other projects. However, the majority of these remain in their conceptual phases. The broader spatial aspect of the urban regeneration program is related to growing interest from the private sector. In recent years, new residential buildings, hotels, business centres and shopping centres have been built in the city centre. Urban regeneration stimulated by the local authorities, which was so far limited to small areas, has now been expanded to almost all districts in the city centre, becoming part of the strategic vision for the city’s development.

Data collection and methodology

Our study to assess these regeneration efforts used an original methodological approach, following the Mixed-Methods Research concept (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004). It involved desk research analysis, supported by qualitative content analysis. Using this methodology, we were able to analyse urban regeneration programs and information provided by the local authorities of Poznań in reports on regeneration programs and projects in the years 2006–2017. We focused on items such as urban regeneration goals, areas subject to regeneration, types of regeneration projects and actors involved in the regeneration process. Following this, we conducted questionnaire interviews among randomly selected adult individuals who were inhabitants of the regenerated areas. The sample included 200 respondents spread across four regenerating neighbourhoods which together have a resident population of 8,000. In other words, for these neighbourhoods, the survey response constituted 2.5 per cent of the population, and thus may be seen as representative of that area. However, this sample is not representative of the entire revitalization area in Poznań. Among the respondents, there were slightly more women (103 individuals; 51.5 per cent) than men (97 individuals; 48.5 per cent). The majority were in younger age groups, with 27 per cent (54 individuals) being under 25 and 42 per cent (84 individuals) between 25 and 35; 17 per cent (34 were aged 36 to 50, 11 per cent (22) between 51 and 65 years, and just three per cent (six individuals) over 66. 39 per cent of respondents (79 individuals) had higher education and 37 per cent secondary education (73 individuals). Almost one in five respondents had a vocational education (19 per cent, 38 individuals), whilst just five per cent (ten individuals) had only completed primary school. The vast majority (74 per cent) were professionally active, with just six per cent unemployed. Of the remainder, students accounted for 11 per cent (22 individuals) and pensioners nine per cent (18 individuals).

The questionnaire provided the respondents with an ordered set of 23 questions, both open-ended and closed. The questions focused on the inhabitants’ knowledge of the regeneration activities conducted in their district (regeneration programmes and projects), their involvement in these activities, the changes observed in the social structure, characteristics of households found currently in the regenerated area, changes in living costs including property prices and their satisfaction with the place where they live.

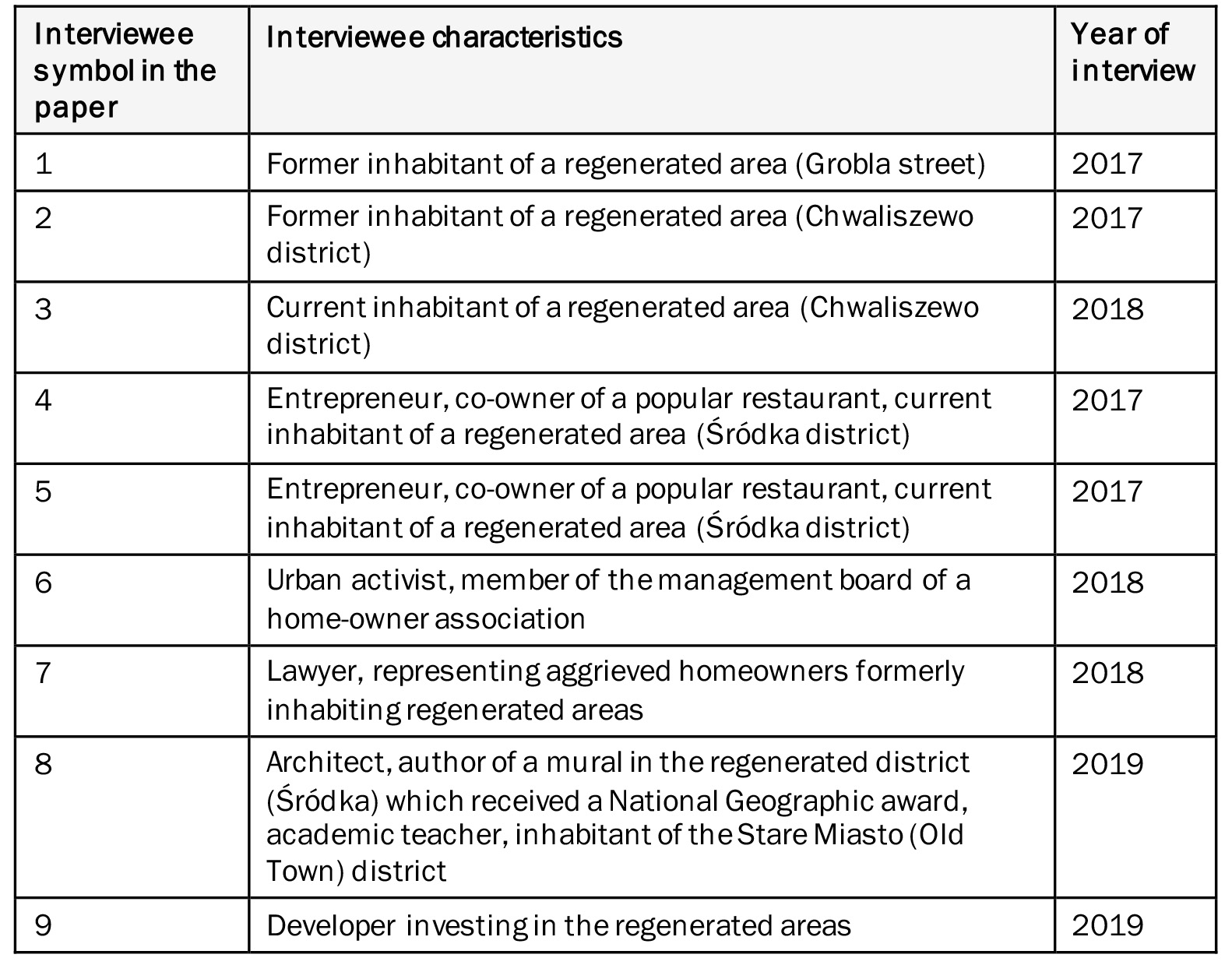

Additionally, a purposive sampling method (Churchill, 2002; Babbie, 2007) was used to gain deeper insights into regeneration effects and practices. We conducted nine individual in-depth interviews whose aim was to obtain qualitative data related to the results of questionnaire surveys. Interviews were conducted with nine individuals representing different social groups (Table 1). The criterion for selecting participants for the sample was their active involvement in revitalization and gentrification processes. Most of the interviewees have a political or economic stake in the revitalized neighbourhoods. The interview questionnaire consisted of 14 questions divided into three categories: living conditions, area regeneration (involvement in regeneration, opinion on implemented regeneration projects) and gentrification of the area (opinion on social and economic changes in the areas subject to regeneration).

The interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 1 hour and 15 minutes and were recorded. In the next section, the interview material is analysed to determine the opinion on social and economic changes occurring in the regenerated areas and on expected future changes in these areas.

Opinion of residents and other actors on regeneration and gentrification

Urban regeneration is a process of changes occurring in the social, spatial and economic sphere. This three-way distinction is used here to present the results of our sociological study conducted among stakeholders participating in the regeneration of Poznań. As mentioned above, the purpose of the study was to evaluate the existing results of urban regeneration and to search for their relations with the gentrification process with particular emphasis on displacement.

Social effects

The key aspect of regeneration should be the social changes that result in improving the life situation of inhabitants of regenerated areas. However, regeneration often has the opposite effect and involves community displacement. A similar situation occurred in Poznań. The vast majority of inhabitants taking the survey (147 individuals; 73.5 per cent) believe that the social structure of the regenerated districts they inhabit has changed. The dynamic change in the social structure of the regenerated districts was also highlighted during the in-depth interviews. Some interviewees spoke openly about the ongoing replacement of the social fabric.

“In general, surely a (social – authors note) change has occurred. One community was replaced with another. It is hard to say whether it is a good thing or bad.” (9)

“Definitely, fast-paced replacement of social fabric is taking place. The intensity of this process is different in various districts and in various periods. Sometimes, this community displacement is accelerated by evictions, known as “clearing tenement buildings”, which has occurred in all districts.” (6)

“(…) within the last three years the social structure has changed. New developments attracted new people of higher social standing. This was accompanied by the outflow of poorer people.” (2)

The survey results confirmed that very few original inhabitants remained in the regenerated areas. Only one in three inhabitants in the survey had been living in the regenerated district for longer than six years. Thus, the majority belonged to the first generation inhabiting the area. Only one in four respondents was a member of a family who had lived in the regenerated area for at least two generations. Moreover, the in-depth interviews highlighted the dominance of the newcomers over the original inhabitants of the regenerated areas, resulting from the former’s higher social standing and greater affluence. It was suggested that of the original inhabitants, only those who fit the new social composition remained.

“Who lives in those buildings? Newcomers. In reality, such building projects bring about the replacement of inhabitants. This is obvious. Fortunately or unfortunately. Depends on how you look at it. These are just objective criteria. Simply put, the majority of people who lived there would not be able to afford to stay.” (9)

“Ever since I moved in, I’ve noticed fewer and fewer poor people but also I noticed fewer cases of social dysfunctions, such as crime, related to lack of financial means. On the other hand, the newly refurbished tenement buildings attract members of the middle class at the very least, whose income allows them to buy or rent flats.” (3)

“(…) from the original inhabitants, only those who fit the new social order, those who can afford it, remain.” (6)

One of the speakers highlighted that in his opinion the replacement of the social fabric was inevitable. At the same time, he admitted to some moral dilemmas that bother him, a developer investing in regenerated areas. There were also some who claimed that those original inhabitants who did remain in the regenerated areas now feel lonely and alienated.

“Today, I do not know any of the people who live in the building I’ve lived in for over half a century. I think other people who remained in the area have similar feelings.” (1)

“Returning to the past inhabitants… Well, the investment processes forced them to move out. The majority could not afford to buy flats or to pay the rent.” (9)

“(…) these flats [are – authors’ note] inhabited for a short time only (Airbnb), often it is one of many flats, a clear change in the character of those flats is noticeable. The original inhabitants are not able to cope with that, they feel this place no longer belongs to them.” (6)

“Those who have lived here for longer sometimes feel lonely and alienated but those who moved in seem content and happy to live in this location.” (3)

“I’ve never liked any of this. I kept wondering if we were doing the right thing. There are those accusations that we are changing the social structure, that when a developer comes, hordes of rich people follow and immediately move in… It is a different world… something completely different. The community will be completely different. On the other hand, I saw how the people who lived there lived weak, poor lives, not to say that they drove each other [towards being socially dysfunctional – authors’ note]. I do not want to say that these people were unhappy, but in reality… these were often substandard flats. Yet, they had lived there for 20, 30 years…” (9)

The interviewees highlighted not only the replacement of the social fabric but also the change in the dominant character of the regenerated districts from being permanently inhabited to being periodically inhabited – in other words, becoming ‘rental areas’. They also noticed the shift towards tourism in these areas and its consequences: the increasing number of bars and restaurants, hotels or hostels or apartments for short-term rental.

“[The social structure – authors’ note] has changed considerably. It is a very dynamic process, the social structure changes all the time. The poorest are at the biggest disadvantage, because without any protection from the city, they are forced to move out. The number of individuals registered for permanent residence decreases all the time, while the number of individuals registered for temporary residence increases (…). In the regenerated districts, it is preferable to get temporary inhabitants, those who will not live there for longer, so that they cannot make use of any legal regulations in case the building’s status is to be changed (for example, into a bank) and they are easier to remove.” (6)

“I thought that people will want to buy apartments and live in locations such as Chwaliszewo or Śródka, yet they buy them for investment purposes. This means they are rented out. (…) I could count the people who bought apartments in Chwaliszewo to live there on one hand.” (9)

“I live in the Old Town district, in the very centre of the city, so I can see this process with my own eyes. Owners refurbish buildings and adapt them into hotels, hostels, sometimes into dormitories for exchange students. I see very few actual inhabitants. This means that the Stare Miasto has become, what do they call it… a showroom, yes?” (8)

The surveys demonstrated that in most regenerated areas a majority of respondents (56 per cent) lived in households of one or two individuals. These were mostly couples without children and single persons (both young and elderly). Additionally, households with three or more people were usually composed of students who share apartments to lower their costs of living or young couples with a single child. One of the interviewees said that in her opinion the regenerated districts are not suitable for families with children.

“My husband always tells me: “What if they open a hostel next door? Your life will be a nightmare with them having parties every weekend.” That is the way it is. Or they will open a club downstairs. To put it brief, for me a family person with children, this is not a good place. (…) This is no longer a place for families with children.” (7)

Spatial effects

Spatial changes are an indispensable component of urban regeneration. Usually, these changes are the first to occur and they are very clearly visible to everyone entering the areas subject to regeneration. It was similar in the case of inhabitants of areas subject to regeneration in Poznań. The most important spatial results of regeneration that they noticed included the refurbishment of building facades (39 per cent mentioned this); the arrival of new street furniture (25 per cent); new green areas (16 per cent);. the modernisation of public spaces (ten per cent); and the development of the area to better promote cultural life in the district (also ten per cent). Additional information on these changes is provided in the opinions expressed by participants in the in‑depth interviews. They present a new image of the previously neglected areas, emerging as a result of improved aesthetics:

“If I were to judge, then of course, spatial changes are positive. I observe them both as an investor in these areas and an inhabitant of Poznań. These changes are immense (…). I remember those sites from twelve, thirteen years ago and a complete change has occurred. I don’t mind if I say that this is a totally different place now.” (9)

“Earlier, there was only sand and some shrubs there. Now it is a very pretty place. They planted trees, built benches and some playgrounds for children. This park has surely helped bring life to the neighbourhood.” (1)

However, while evaluating spatial changes in the regenerated areas, some interviewees noticed problems related to these, mostly social but also related to architecture and urban planning.

“You have to look at this from two standpoints. One is that of someone who walks or drives around Poznań. It is true, now everything is pretty and new, refurbished. (…) We have these beautiful facades and all. It all seems more beautiful and newer. However, my approach is strongly affected by my contacts with people who are the victims of these processes. In all honesty, when I look at those old tenement buildings, I keep wondering what became of the people who lived there.” (7)

“There is no protection for them(…) and there is no protection for architecture, either. Next to the [historical tenement buildings in Śródka – authors’ note] a residential building is being constructed which will completely change the landscape of Śródka.” (6)

One of the interviewees even questioned whether the term ‘regeneration’ was understood correctly. The interviewee claimed that having observed the results of activities conducted in Poznań, we should not be calling it regeneration, but something opposite.

“In Poznań, the so-called regeneration process gravitated towards building and sometimes refurbishing buildings, while people were marginalised. I believe that in this case, we are talking about the degeneration of certain areas. (…) For me, regeneration means restoring vitality, revitalising. But this cannot be done with stones. We can build thousands of buildings, stones as I call them, but they will remain dead, they will not be an answer to people’s needs, they will not serve their inhabitant.” (8)

The same person also highlighted that in his opinion, changes made to the building structure may only be considered regeneration if they are the material result of activities conducted together with the people inhabiting the given area. To justify his claims, the interviewee provided examples of several building projects in the regenerated areas which were implemented without the cooperation of local communities and, as a result, they have still not integrated until today.

Economic effects

Another aspect of the regeneration process are the economic changes. The vast majority of respondents (84.5 per cent) were of the opinion that the value of their apartments has increased as a result of regeneration. This view was also shared by those participating in the in-depth interviews. At the same time, some of the speakers noted that the increase in the value of apartments and rent increases in regenerated areas was the cause of inhabitants being replaced.

“Yes, it is my view that the value of apartments and rents in tenement buildings [in the regenerated areas – authors’ note] that are not owned by the city has increased considerably. We also encountered cases of tenement buildings being sold in regenerated areas, which resulted in the replacement of their inhabitants. Developers were very willing to invest in those districts due to the new potential, the regeneration, the focus on tourism and students.” (6)

“The apartments in buildings in regenerated areas that I know of maintain their value -it does not decrease in any way. I can guarantee that their value is higher than that of new apartments built in other locations. (…) Their prices are closer to those that are obtainable in the developers’ market in what we call premium projects.” (9)

“Did the value of apartments increase in the regenerated areas due to regeneration? That is for sure. It would be difficult to argue otherwise. Currently, these apartments represent a different standard. Their value has increased considerably. There can be no doubt about that.” (7)

“(…) we are certain that regeneration affected the property values considerably. However, I do not know if this was planned at all…(…). The rents for commercial premises, for apartments all changed, all went up. I remember when we just had Cafe la Ruina [the first restaurant in the regenerated Śródka district – authors’ note], an appraiser came, he was having coffee, and he told us that everything is changing, that it is also our spot that makes people come here.” (4, 5).

Changes occurring in the regenerated districts of Poznań are also reflected in the scope of the services available. During the interviews, respondents noted that the services available now are different to what was available in the past. They said that new services such as expensive cafes and restaurants or medical services are not only beyond the financial reach of original inhabitants but also lie outside the spectrum of their needs, and sometimes they are even a nuisance to them.

“[The scope of available services – authors’ note] has changed considerably to services for outsiders, tourists and new inhabitants. These services, including expensive restaurants, are available to the middle and upper class. At the same time, there are events that are a nuisance to the original inhabitants. They do not participate in them, they consider it a nuisance.” (6)

“The character [of services – authors’ note] is changing. These are new services. In the case of Chwaliszewo, only doctors appear. Among six commercial premises, five are now occupied by medical services. In one we have gastronomic services (…), a restaurant. It was not there before.” (9)

“Certainly. It is visible that today [new services – authors’ note] appear instead of those that are useful to inhabitants. We have some cafes, we have all those things that I do not associate with meeting people’s basic needs, such as a cobbler, a grocery store. We have sophisticated goods and services available. These are things that are not available to certain groups within the society, but also not within the scope of their needs.” (7)

“(…) the original inhabitants are not happy, because, as they say, this is no longer their space, but the new inhabitants are happy [with the new services – authors’ note] for sure as they are tailored to their needs.” (6)

In this context an interesting question is the future of the regenerated districts, especially given the expansion of the regeneration area in Poznań in 2017. When asked if they will be able to afford their apartment in a regenerated area, the respondents had mixed opinions. A large proportion (45 per cent) said that it is difficult to answer this question, whereas a slightly less numerous group (41 per cent) had no doubt they would be able to cover the costs of living in their apartment in the future. However, in light of the fact that nearly 45 per cent of the respondents have lived in the regenerated areas for less than three years, it might be assumed that such an answer was given mostly by the new inhabitants. One in seven respondents said that in the future they would not have sufficient means to pay for the apartment. The interviewees highlighted the excessive involvement and importance of developers in the regeneration process which, coupled with the lack of adequate intervention by the city authorities and a very low number of communal flats, may lead to a further increase in the cost of living in the regenerated areas. The interviewees claimed that only actions taken by the city authorities to guarantee access to apartments below market prices could prevent the outflow of local inhabitants. It was highlighted that the financial means of many of those affected will be insufficient to pay high rents.

“Since it’s mostly developers – private investors and property managers – who are involved in the regeneration process while the city authorities less so, I am afraid that the costs may increase considerably in the years to come.” (3)

“If this is directed towards the position of a developer, the claim that every price for buying/renting a flat is acceptable, these inhabitants will no longer be there. So far, this has been going on. However, if the city introduced a flat rental policy, as communal flats or social flats, at a good price, then these people will stay.” (8)

“Will (…) the inhabitants be able to pay for their flats in the nearest future in the districts subject to regeneration? There is a problem with that. Of course not. There are lots of people like that. I do not know the exact numbers, I am not a person who deals with numbers. However, I am in contact with those members of society who come to me and tell me: “My pension is PLN 1600 per month, my rent is PLN 1200”. And this is not the worst situation. Sometimes the rent is equal to their entire income.” (7)

“The rents will increase and this will be a problem. I base my assumptions on the information on what has been going on so far. Inhabitants had to move out of the buildings belonging to the city. Only buildings belonging to the city can guarantee any protection.” (6)

The opinions of the respondents reveal a certain resentment towards the regeneration process. The developers and the middle class are considered the biggest beneficiaries of the process and the lack of legal regulations protecting the original inhabitants is blamed for this situation. Such regulations are not included in the Urban Regeneration Act of 2015. Their exclusion was justified by the high costs that would be incurred by the state and local authorities, and also by the unwillingness to artificially regulate the real estate market.

“Here, we come back to the sources of the regeneration process which was born somewhere in the West. It is something that has not been done in our country, at a national level. We did not formulate our urban regeneration laws and certain processes so that at the beginning of the regeneration process rents and property prices were frozen to prevent them from increasing and to make it impossible to speculate on land. This was not done.” (8)

“I would very much like to recommend the regenerated areas but the problem is that they are safe places only for those who, owing to their very good financial situation, will not experience the negative results of gentrification. These are only the rich people.’ (6)’Who benefited the most from the regeneration in Poznań? People who had some means and were able to make money on these properties. This is a very small group of people, who were able to purchase a tenement building and invest in it.” (7)

At the beginning of regeneration in Poznań, it was assumed that social activities would be the basis for further action. This was supposed to prevent gentrification. Despite these endeavours, and the launching of numerous social initiatives also in collaboration with the inhabitants, the final result was the opposite to what was intended. It turns out that the issue most often mentioned as a reason for negative opinions of regeneration in Poznań is the incorrect preparation of regeneration programs, which did not predict the social changes that have occurred in the regenerated areas.

“Time showed and the experience of our home-owner association confirmed that the regeneration programs that were implemented brought about many negative changes, which may be described as gentrification. These programs did not predict the negative outcomes. Rents were not protected, services were not protected. The negative results of regeneration processes have not been noticed.” (6)

Conclusions

Our study has revealed that the regeneration process has led to positive spatial effects. It resulted in a considerable improvement in the condition of buildings and land development in the regenerated areas. The standard of living improved, building facades were refurbished, spaces for outdoor activities, such as parks and squares, were created, numerous improvements were provided for bicycle and pedestrian traffic. At the same time, new private buildings were erected in the regeneration areas for the middle class and for rent (also short-term). Property-led regeneration is therefore an important dimension of changes taking place in deprived areas in Poznań (see Turok, 1992). What is preoccupying, however, is that new private investments are often ill-adapted to the surroundings, their architecture is mismatched with the historical buildings which dominate in these areas.

The social repercussions of the regeneration process turned out to be extremely disappointing. Despite numerous social activities, it was impossible to prevent the outflow of the original inhabitants caused by the regeneration. The only technique used to prevent displacement – community empowerment – proved ineffective (see Shaw, 2005). Public participation did not move up to the decision‐making level, which weakened local community motivation (see Ghaffari et al., 2018). Ultimately, the final result was the opposite to what was intended. The original residents were replaced with new ones, with a better financial status. At present, regenerated areas are predominantly inhabited by newcomers – the first generation of small, middle-class households. Only a few people are members of families who have lived in the regenerated areas for at least two generations and those who remain now feel alienated. In addition, the dominant character of the regenerated districts has changed from being permanently inhabited to being periodically inhabited, with a large number of flats being used for short-term rental.

The character of services in regenerated areas has also changed. The number of bars and restaurants, hotels and hostels has increased, and other available premises are used by law firms, private medical facilities and beauty parlours. These new services are better suited to the needs of new inhabitants rather than those of people who originally lived in the areas. The research shows, therefore, that gentrification in Poznań concerns not only social change but also economic changes, including those related to new services available to residents (see Smith, 1987).

Further displacement in the regenerated areas is predicted. This is the result of the rise in real estate prices, the very limited number of communal flats and the dominance of developers’ investment projects. As Levy et al. (2007) notes, affordable housing provision strategies aimed at considering the needs of low-income residents are the key to counteracting the negative aspects of gentrification. In the case of the latter, the purchase price or rent is dictated by the real estate market and not the social policy of local or state authorities.

In conclusion, the outcome of the regeneration initiatives may be considered as unsatisfactory. The plans related to improving the condition of buildings and land development were implemented successfully, unlike those related to enhancing the living situation of people inhabiting the regenerated areas. Urban regeneration resulted in the gentrification of all districts in the city centre and no social benefits were obtained. One of the interviewees asked the following question about the direction of changes occurring in Polish cities: ‘Are the cities going to thrive with their inhabitants, or will they become like shopping centres: come in, do your shopping, now we’re closing, goodbye?’ (8) Taking into consideration the opinions collected in this paper, it may be concluded that Poznań is coming dangerously close to the latter scenario. According to Bernt (2016), while gentrification is made possible, and is even promoted, by local policies, it is also state policies that can provide protection for the poor in the process. Although it is not usually a long-term solution, it allows displacement to be stopped, at least in the initial phase (Ley and Dobson, 2008). In Poland, national authorities have decided against using almost any tools to guard against gentrification, such as public intervention or rent controls. The example of Poznań proves that unregulated physical regeneration promoted by local authorities is a simple way to initiate gentrification.

Adam Mickiewicz University, Wieniawskiego 1, Poznań, Poland. Email: przemko@amu.edu.pl ; basic@amu.edu.pl

Auger, D. A. (1979) The Politics of Revitalization in Gentrifying Neighborhoods: The Case of Boston’s South End. Journal of the American Planning Association, 45, 4, 515-522. CrossRef link

Babbie, E. (2007) Badania społeczne w praktyce. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Badcock, B. (1995) Building upon the foundations of gentrification: inner-city housing development in Australia in the 1990s. Urban Geography, 16, 1, 70-90. CrossRef link

Badyina, A. and Golubchikov, O. (2005) Gentrification in central moscow‐a market process or a deliberate policy? money, power and people in housing regeneration in ostozhenka. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 87, 2, 113-129. CrossRef link

Bardzińska-Bonenberg, T. (2012) O gentryfikacji zabytkowych rejonów w Poznaniu. Czasopismo Techniczne, 1-A/1, 43-52.

Bernt, M. (2016) How post-socialist is gentrification? Observations in East Berlin and Saint Petersburg. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 57, 4-5, 565-587. CrossRef link

Bernt, M., Gentile, M. and Marcińczak, S. (2015) Gentrification in Post-communist Countries: An Introduction. Geografie, 120, 2, 104–112. CrossRef link

Borgegard, L. and Murdie, R. (1993) Socio-demographic impacts of economic restructuring on Stockholm’s inner city. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 84, 4, 269-280. CrossRef link

Chelcea, L. (2006) Marginal Groups in Central Places: Gentrification, Property Rights and Post-Socialist Primitive Accumulation (Bucharest, Romania). In: Enyedi, G. and Kovács Z. (eds), Social Changes and Social Sustainability in Historical Urban Centres: The Case of Central Europe, Pecs: Centre for Regional Studies of Hungarian Academy of Science, 107–126.

Churchill, G. A. (2002) Badania marketingowe. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Ciesiółka, P. (2010) Zjawisko gentryfikacji na obszarach Miejskiego Programu Rewitalizacji dla Miasta Poznania. In: Grzelak-Kostulska E., Hołowiecka B. (eds) Zmiany obszarów miejskich i wiejskich w świetle wybranych analiz demograficznych i funkcjonalno-przestrzennych. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. M. Kopernika, 99-112. CrossRef link

Ciesiółka, P. (2014) The impact of European Union funds on revitalization process in Poznań in comparison to the biggest cities in Poland. In: Churski P., Stryjakiewicz T. (eds) POZNAŃ – an attempt to assess changes during 10 years of membership in the European Union, Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 65-78.

Ciesiółka, P. (2018) Urban Regeneration as a New Trend in the Development Policy in Poland. Quaestiones Geographicae, 37, 2, 109-123.

Clark, E. (2005) The order and simplicity of gentrification‐ a political challenge. In: R. Atkinson and G. Bridge (eds), Gentrification in a global context: The new urban colonialism. London: Routledge, 256–264. CrossRef link

Davidson, M. and Lees, L. (2005) New‐build ‘gentrification’ and London’s riverside renaissance. Environment and Planning A, 37, 1165–1190. CrossRef link

Dolata, D. (2012) Przemiany poznańskiej Śródki: rewitalizacja czy gentryfikacja? In: K. Derejski, J. Kubera, S. Lisiecki, R. Macyra (eds) Deklinacja odnowy miast. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Wydziału Nauk Społecznych UAM.

Dudek-Mańkowska, S. and Iwańczak, B. (2018) Does gentrification of the Praga Północ district in Warsaw really exist? Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 39, 21-30. CrossRef link

Feldman, M. (2000) Gentrification and social stratification in Tallinn: strategies for local governance. SOCO Project Paper (86). Vienna: Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen.

Florida, R. (2015) This is what happens after a neighborhood gets gentrified. The Atlantic, September 16th. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/09/this-is-what-happens-after-a-neighborhood-gets-gentrified/432813/ [Accessed: 11/11/2020]

Ghaffari, L., Klein, J-L. and Angulo Baudin, W. (2018) Toward a socially acceptable gentrification: A review of strategies and practices against displacement. Geography Compass, 12, 123–155. CrossRef link

Golubchikov, O. and Badyina, A. (2006) Conquering the inner-city: Urban redevelopment and gentrification in Moscow. In: Tsenkova S. and Nedović-Budić Z. (eds) The Urban Mosaic of Post-Socialist Europe. Contributions to Economics. Physica-Verlag HD, 195-212. CrossRef link

Górczyńska, M. (2017) Gentrifiers in the post-socialist city? A critical reflection on the dynamics of middle- and upper-class professional groups in Warsaw. Environment and Planning A, 49, 5, 1099-1121. CrossRef link

Haase, A., Steinfuhrer, A., Kabisch, S., Grossman, K. and Hall, R. (eds, 2012) Residential Change and Demographic Challenge. The Inner City of East Central Europe in the 21st Century. London: Ashgate.

Hlaváček, P., Raška, P. and Balej, M. (2016) Regeneration projects in Central and Eastern European post-communist cities: Current trends and community needs. Habitat International, 56, 31-41. CrossRef link

Jachowska, J. (2016) Wilda – o społecznych skutkach gentryfikacji. Przegląd Zachodni, 2, 359, 181-198.

Jakóbczyk-Gryszkiewicz, J., Sztybel-Boberek, M. and Wolaniuk, A. (2017) Post-socialist gentrification processes in Polish cities. European Spatial Research and Policy, 24, 2, 145-166. CrossRef link

Jarczewski, W. and Dej, M. (2015) Rewitalizacja 2.0. Działania rewitalizacyjne w Regionalnych Programach Operacyjnych 2007–2013 – ocena w kontekście nowego okresu programowania. Studia Regionalne i Lokalne, 1, 59, 104–122.

Jarczewski, W. and Kułaczkowska, A. (2019) Raport o stanie polskich miast Rewitalizacja. Warszawa – Kraków: Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów.

Johnson, R.B. and Onwuegbuzie, A.J. (2004) Mixed Methods Research A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher, 33, 14-26. CrossRef link

Kährik, A. (2006) Socio-spatial residential segregation in post-socialist cities: the case of Tallinn, Estonia. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

Kaźmierczak, B., Nowak, M., Palicki, S. and Pazder, D. (2011) Oceny rewitalizacji. Studium zmian na poznańskiej Śródce. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Wydziału Nauk Społecznych UAM.

Kovács, Z. (1998) Ghettoization or gentrification? Post-socialist scenarios for Budapest. Netherlands Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 13, 1, 63. CrossRef link

Kovács, Z., Wiessner, R. and Zischner, R. (2013) Urban renewal in the inner city of Budapest: Gentrification from a post-socialist perspective. Urban Studies, 50, 1, 22-38. CrossRef link

Kowalewski, A., Markowski, T., Śleszyński, P., Nauk, P. A., and Kraju, K. P. Z. (eds, 2018) Koszty chaosu przestrzennego. Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju PAN.

Kusiak, J. (2017) Chaos Warszawa: porządki przestrzenne polskiego kapitalizmu. Fundacja Nowej Kultury Bęc Zmiana.

Lees, L., Slater, T. and Wyly, E. (2013) Gentrification. New York: Routledge. CrossRef link

Levy, K., Comey, J. and Padilla, S. (2007) In the face of gentrification: Case studies of local efforts to mitigate displacement. Journal of Affordable Housing, 16, 3, 238–315.

Ley, D. and Dobson, C. (2008) Are there limits to gentrification? The contexts of impeded gentrification in Vancouver. Urban Studies, 45, 2471–2498. CrossRef link

Maloutas, T. (2011) Contextual Diversity in Gentrification Research. Critical Sociology, 38, 33–48. CrossRef link

Nowak, M. (2013) Niezrealizowana rewitalizacja jako niedoskonała gentryfikacja. Analiza procesu ożywiania poznańskiej Śródki. Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny, 75, 229-249. CrossRef link

Parysek, J. (2008) Suburbanizacja i reurbanizacja, dwa bieguny polskiej urbanizacji. In: Parysek, J., Stryjakiewicz, T. (eds), Region społeczno-ekonomiczny i rozwój regionalny. Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

Roberts, P. (2010) The evolution, definition and purpose of urban regeneration. In: P. Roberts, H. Sykes (eds), Urban regeneration. A handbook. London: Sage, 9-36. CrossRef link

Shaw, K. (2005) Local limits to gentrification: implications for a new urban policy. In: Atkinson R. and Bridge G. (eds), Gentrification in a global context: The new urban colonialism. London: Routledge, 168–184. CrossRef link

Smith, N. (1987) Gentrification and the rent gap. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 77, 3, 462–465. CrossRef link

Swianiewicz, P., Krukowska, J. and Nowicka, P. (2011) Zaniedbane dzielnice w polityce wielkich miast. Warszawa: Elipsa.

Sykora, L. (1996) Economic and social restructuring and gentrification in Prague. Acta Facultatis Rerum Naturalium Universitatis Comenianae (Geographica), 37, 71-81.

Sykora, L. (2005) Gentrification in Post-communist Cities. In: Atkinson, R. And Bridge, G. (eds), Gentrification in a Global Context. The New Urban Colonialism. New York–London: Routledge, 90–105. CrossRef link

Szlachetko, J.H. and Borówka, K. (eds, 2017) Ustawa o rewitalizacji. Komentarz. Gdańsk: Instytut Metropolitalny.

Turok, I. (1992) Property-Led Urban Regeneration: Panacea or Placebo? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 24, 3, 361–379. CrossRef link

Wiest, K. (2012) Comparative debates in post-socialist urban studies. Urban geography, 33, 6, 829-849. CrossRef link

Wyly, E., Newman, K., Schafran, A. and Lee, E. (2010) Displacing New York Environment and Planning A, 42, 11, 2602–2623.