- Sydney Adventist Hospital Clinical School, Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney, Wahroonga, NSW, Australia

Despite the availability of thrombolytic and endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke, many patients are ineligible due to delayed hospital arrival. The identification of factors related to either early or delayed hospital arrival may reveal potential targets of intervention to reduce prehospital delay and improve access to time-critical thrombolysis and clot retrieval therapy. Here, we have reviewed studies reporting on factors associated with either early or delayed hospital arrival after stroke, together with an analysis of stroke onset to hospital arrival times. Much effort in the stroke treatment community has been devoted to reducing door-to-needle times with encouraging improvements. However, this review has revealed that the median onset-to-door times and the percentage of stroke patients arriving before the logistically critical 3 h have shown little improvement in the past two decades. Major factors affecting prehospital time were related to emergency medical pathways, stroke symptomatology, patient and bystander behavior, patient health characteristics, and stroke treatment awareness. Interventions addressing these factors may prove effective in reducing prehospital delay, allowing prompt diagnosis, which in turn may increase the rates and/or efficacy of acute treatments such as thrombolysis and clot retrieval therapy and thereby improve stroke outcomes.

Introduction

The “time is brain” concept introduced more than two decades ago (1) encapsulates the crucial importance of time in treating acute stroke. This has become more pertinent since the advent of thrombolysis treatment using tissue plasminogen activator (2, 3) and endovascular therapy (4). Regarding thrombolysis, benefit has been shown for initiating treatment up to 4.5 h after acute stroke onset (5, 6). A major obstacle to their use however is a long onset-to-door time (from stroke symptom onset or time last known well to hospital arrival), which in general is the largest component of total onset-to-needle time (from stroke onset to thrombolysis) (7, 8).

Previous reviews of prehospital delay have shown little improvement in onset-to-door times over the years (7, 8). Much effort to reduce door-to-needle times have led to remarkable improvements (9); however, these efforts on reducing in-hospital delay are diminished by the minimal improvements in prehospital delay. The battle to increase thrombolysis rates will remain futile unless significant improvements are seen in reducing onset-to-door times after acute stroke (8, 10).

Reducing the time to hospital arrival is crucial for prompt diagnosis and timely delivery of therapies such as thrombolysis and clot retrieval. However, analysis of trial data has not consistently shown a relationship between time to treatment and better outcomes (11–13). Nevertheless, early arrival will naturally lead to a higher proportion of acute strokes arriving within the therapeutic time windows, conferring improved outcomes on a higher proportion of patients, regardless of whether there is increased benefit earlier in the 4.5-h thrombolysis time window. A study analyzing the baseline penumbra volume, baseline ischemic core volume, and the penumbra salvaged from infarction after thrombolysis, showed that greater penumbral salvage had the greatest effect on disability-free life, rather than onset to treatment time (14). However, this does not negate the importance of early presentation in this context, as it allows more time for prompt clinical and imaging assessment. Moreover, earlier presentation should allow for a more extensive evaluation of stroke mimics and potential misdiagnoses (15–17), within the time window of eligibility for acute stroke therapies.

The identification of factors associated with early or delayed hospital arrival after stroke is of crucial importance in improving thrombolysis rates (10, 18) and by extrapolation the rates of other acute interventions. We therefore conducted a review of studies that analyzed factors associated with either early or delayed hospital arrival after stroke, with the aim of identifying modifiable targets of interventions in reducing prehospital delay. Knowledge of these factors may be helpful in reducing onset-to-door times, and thus increase the implementation rates of acute stroke therapies.

Review Methods

A search of MEDLINE was performed via Ovid (http://ovidsp.ovid.com) using a previously published search strategy (7, 8) between 2008 to the access date of November 1st 2016. For the years prior to 2008, references of previous reviews were examined (7, 8, 10, 18, 19). The same search strategy was also used in Embase via Ovid excluding MEDLINE journals but with no limit on publication year. Studies not published in English, review articles, and Letters to the Editor were excluded. The following were also excluded: studies focusing solely on transient ischemic attacks (TIA); studies that reported on hospital arrival times but did not analyze factors associated with early or delayed arrival; studies on decision delay after stroke; studies on delay to alerting medical services or delay to first medical contact, and delay to admission to stroke unit; and studies on factors associated with Emergency Medical Services (EMS) use.

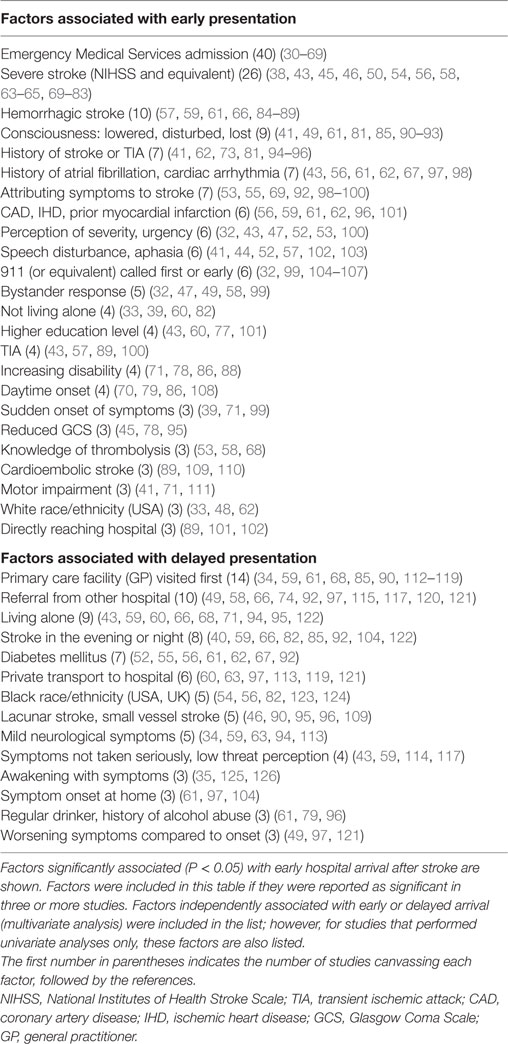

115 studies, published between 1990 (20) and 2016 (21) reporting on data acquired between 1985 (20) and 2013 (22), were identified that focused primarily on analyzing factors associated with early or delayed hospital arrival after stroke. From these studies, factors significantly associated with early or delayed hospital arrival were extracted and are listed in Table 1. Factors from studies that did not describe any statistical analyses were excluded (22–29). Factor data were excluded from one study which defined early arrival as before 24 h (20).

Median onset-to-door times, and the cumulative percentage of patients arriving at hospital within: 1, 2, 3, 6, and/or 24 h (majority of studies described data for these time intervals), were collected when available. When median times were lacking in a study, but a percent arriving before a given hour was 50% (±1%), this time was used as the median arrival time. Similarly, when median times fell exactly on the time intervals above, then 50% was added to the data as the cumulative percentage arriving before that time. When time data were subdivided into certain population subgroups, these were excluded. When time data were obtained over a range of years, the mean of the years was used (8). Time data were excluded from one study that only included patients that received thrombolysis (80). Inclusion criteria based on stroke subtype varied widely (7, 8, 18), for example: stroke and stroke-like symptoms (32), ischemic only (58), ischemic and hemorrhagic (127), stroke excluding subarachnoid hemorrhage (50), intracerebral hemorrhage only (78), and some included TIA (43). Other notable methodological variations were (i) time interval defining early versus delayed arrival; (ii) whether a cutoff was used to exclude prehospital time data from cases of prolonged (e.g., >24 h) delay; and (iii) how prehospital time was defined in cases of patients awakening with stroke (7, 8, 18).

Time from Symptom Onset to Hospital Arrival: Trends Over two Decades

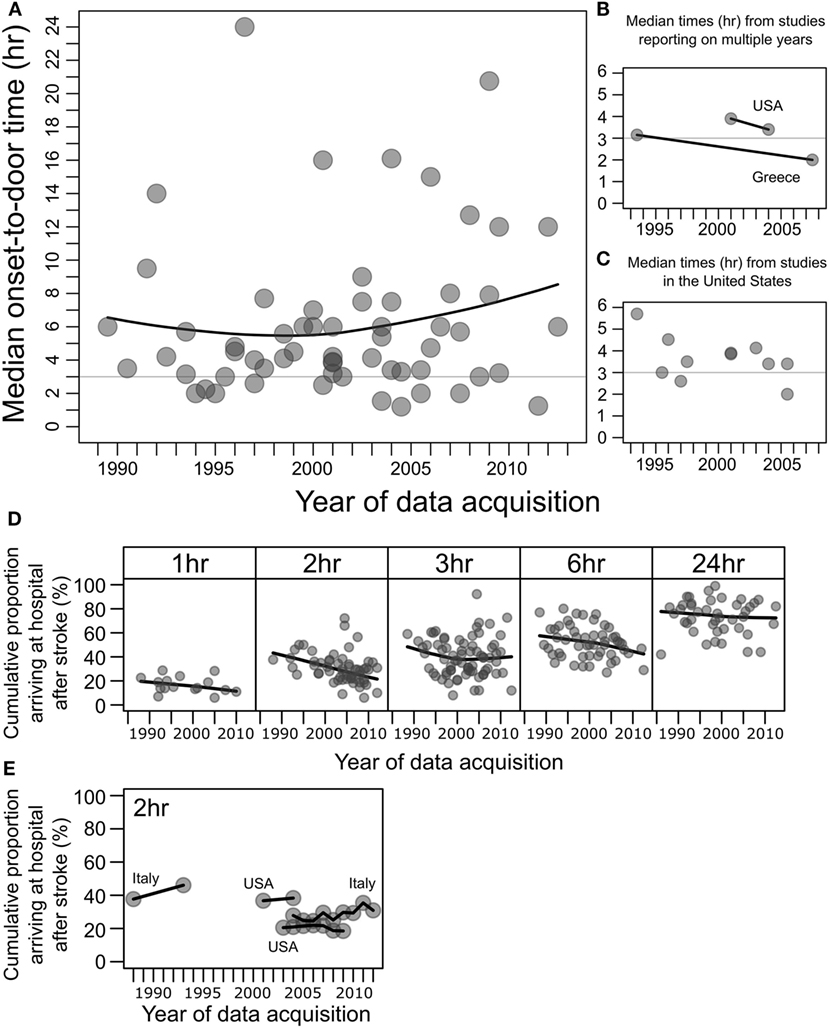

Within the 115 studies reviewed here, 58 studies from 26 countries contained median onset-to-door times and the year/s of data acquisition (Figure 1A). The key and perhaps unexpected result is that onset-to-door time over the years has essentially remained unchanged, as previously reported for data up to 2006 (7, 8). The majority of studies reported a median onset-to-door time well beyond 3 h, which when taking door-to-needle time in consideration, prohibits the effective and timely commencement of thrombolytic therapy. Only two studies (54, 59) showed median onset-to-door times from different years, which exhibited only modest improvements (Figure 1B). Eleven studies originating from the United States, the country with the most studies available for secular trend comparison, showed no meaningful improvement overall (Figure 1C). An analysis of onset-to-door time data from the Get With The Guidelines program between 2003 and 2009 (62) showed essentially no improvement (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Median onset-to-door times after stroke and percentages of patients arriving to hospital after stroke at 1, 2, 3, 6, and 24 h. (A) Data points represent median onset-to-door times (hours) of stroke patients plotted against the year/s of data acquisition, in studies of factors associated with hospital arrival times after stroke, from 58 studies. For studies conducted over multiple years, the mean of the years was taken (8). Black line shows the local polynomial regression (LOESS), and the horizontal gray line indicates 3 h. (B) Median onset-to-door times (hours) from two studies that reported data for multiple years, from the United States (USA) (54) and Greece (59). Black lines connect data from the same study. (C) Subset of median onset-to-door time data in panel (A) showing studies from the United States (31–33, 35, 36, 44, 48, 53, 54, 73), excluding one outlier of median 16 h in 2000–2001 (128). (D) The cumulative percentages of patients arriving to hospital after stroke, at 1, 2, 3, 6, and 24 h after onset. Data points represent percentages from individual studies plotted against year/s of data acquisition. Black line shows the local polynomial regression (LOESS). An improvement in prehospital delay over the years would manifest as an upwards curve within each box, which is not seen. (E) Subset of the cumulative percentage of patients arriving before 2 h from studies that reported on data for multiple years from Italy [1986–1990 to 1991–1995 (71); 2004–2012 (83)] and the United States [2001–2004 (54), 2003–2009 (62)].

Within the 115 studies reviewed here, 100 studies contained data on the cumulative percentage of stroke patients arriving at hospital before at least one of the following time intervals: 1, 2, 3, 6, and/or 24 h, and also the year/s of data acquisition (Figure 1D). The majority of patients failed to arrive before 3 h, and the local regression shows no improvement over the two decades. Four studies (54, 62, 71, 83) showed percentages of patients arriving before 2 h from different years, and these essentially showed no improvement overall (Figure 1E).

Despite the advent of thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke in the late 1990s (2, 3), the majority of patients in the majority of locations around the world failed to arrive at hospital before 3 h (7, 8). When taking door-to-needle time into consideration, which although improving (9) is commonly in excess of 1 h (7, 8), a 3-h onset-to-door time would generally be the maximum delay possible to meet a 4.5-h onset-to-needle time target for thrombolysis (5, 6). Improvements in prehospital time have been stagnant, and it remains the largest component of total onset-to-needle time (7, 8). A dramatic example of this is a study from Greece analyzing 16 years of onset-to-emergency room presentation (prehospital time) and emergency room to completion of CT times (a component of in-hospital time), which showed a more than 10 h decrease in in-hospital time (median of 12.34 to 1.05 h), whereas prehospital time was reduced only by about 1 h (median of 3.15 to 2.0 h) (59).

Factors Associated with Early and Delayed Hospital Arrival after Stroke

From the studies reviewed here, factors associated with either early or delayed arrival after stroke were extracted (Table 1). Patient age and sex were associated in different studies with both early and delayed arrival and are discussed separately.

Hospital arrival by EMS was the factor most frequently associated with early hospital arrival after stroke, with 40 reporting studies. Severe stroke was the second most frequent factor, as measured by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) or other scales. Other factors associated with early arrival were related to stroke symptomatology, stroke subtype, comorbidities, patient and/or bystander behavior or perception at stroke onset, and timing of stroke onset.

The top three factors associated with delayed arrival were if a general practitioner (GP) or primary care facility was visited first, referral from another hospital, and living alone.

The Key to Early Hospital Arrival: EMS

Hospital admission via EMS was by far the most frequently associated factor with early arrival, with the converse non-EMS use, appearing high in the list of factors associated with delay. A review of surveys on the knowledge of what action to take upon stroke symptom onset has shown that, although the majority stated calling EMS, a sizable proportion responded contacting their GP (129). It is essential that educational programs further emphasize contacting EMS immediately upon stroke onset (10, 18).

Three factors frequently associated with delayed arrival were closely related: primary care facility visited first, referral from another hospital, and private transport to hospital. These reveal the importance of patient and/or bystander factors, such as misjudgment at symptom onset or poor awareness of stroke symptoms and emergency pathways, and further stress the necessity of raising the awareness of the variability of stroke symptoms (18). This is exemplified by the fact that mild neurological symptoms, which may be misinterpreted as general malaise and thus minimized in seriousness by patients and bystanders (34), were significantly associated with delayed arrival.

One study that analyzed factors associated with EMS-use after stroke found that of the cases where EMS was activated, only 4.3% of calls were made by the patient compared to 60.1% by family members, stressing the importance of targeting potential latent bystanders (family, caregivers, and coworkers) in educational programs (130). A study of a community and professional behavioral intervention program on stroke identification and management showed an increase in thrombolysis rates between the intervention and comparison group, however not in delay time (131). EMS use is known to have additional benefits beyond shortening of prehospital time. Studies have shown that, due to hospital pre-notification (132), EMS use is associated with prompter evaluation by imaging, shorter door-to-needle times, and increased thrombolysis rates (133). Therefore, the nature of transport to hospital (EMS versus private transport) has an added benefit to in-hospital stroke care beyond the simple shortening of prehospital time.

Stroke Subtype, Symptomatology, and comorbidities

Severe stroke was a major factor associated with early arrival, which is to be expected by its debilitating symptomatology, naturally raising a sense of urgency in the patient or bystander. Interestingly, a history of cardiac arrhythmia or atrial fibrillation (AF) was associated with early arrival. Patients with AF are known generally to present with more severe strokes (134) which may be a contributing factor to early presentation. Patients may also have a latent sense of urgency to present to hospital with new symptoms, because of their known cardiac condition (43), or have a raised awareness of stroke symptoms, with AF being a major stroke risk factor (135).

Diabetes mellitus was associated with delayed arrival after stroke in multiple studies. This may be due to patients or bystanders misinterpreting symptoms as hypoglycemia (92). Moreover, diabetics versus non-diabetics were shown to more likely present with lacunar and ischemic strokes with a lower rate of hemorrhagic strokes (136, 137). Patients with lacunar strokes show delayed presentation and hemorrhagic strokes present earlier (Table 1), and thus the delay in stroke patients with diabetes may be due to differences in stroke subtype or symptomatology rather than diabetes per se. More investigation is required as this may be a promising target for intervention. A number of other vascular risk factors were also associated with delayed arrival (52) such as smoking and hypertension (56, 62).

Perceptual and Behavioral Factors

Perceptual and behavioral factors (99) such as symptoms not taken seriously and low threat perception were also associated with delayed arrival. Past research on stroke knowledge has shown that having stroke risk factors in general does not contribute to an increase in stroke knowledge (129, 138), which further stresses the importance of improving knowledge through public awareness campaigns (18, 139, 140). Such campaigns must target those with stroke risk factors (141), and also be tailored to target minority populations (142). However, the fact that a personal history of stroke or TIA was significantly associated with early arrival points to the effectiveness of the sense of urgency or awareness that comes about by a first-hand experience of cerebrovascular disease in reducing onset-to-door time (71, 94). Family history of stroke was also associated with early arrival (71, 114), and this has also been shown to be an independent predictor of knowing at least one stroke risk factor (143). Promisingly, the knowledge of thrombolysis treatment by patients was associated with early arrival (Table 1).

Time to Hospital Arrival: Male Versus Female and Patient Age

Depending on the study, female compared with male patients were associated with both early (39, 54) and delayed arrival (47, 56, 62, 99, 144, 145). Many factors may contribute to this difference, including comorbidities, prestroke disability (145, 146) and whether they live alone (147, 148). Differences in stroke subtype and symptomatology between men and women may underlie differences in arrival time (148–150), and moreover it is important to consider disparities in stroke outcomes not just arrival times (151).

There is no conclusive relationship between patient age and prehospital time. Studies utilized various methods for analyzing the effect of age. In short, being younger was associated both with early (63, 83, 96) and delayed (57, 91, 126) presentation, and similarly older patients were associated with both early (37, 43, 59, 77, 114) and delayed (56, 57, 62, 74, 83, 121) presentation. There may be a lack of urgency in younger patients with stroke (152), and symptoms exhibited by older patients may be more readily interpreted as stroke and perceived as an emergency (43). Interestingly, a review on studies of stroke knowledge reported that stroke knowledge is generally lowest in the young (18–25 years) and the elderly (≥80 years) (18).

Interaction Between Onset-to-Door and Door-to Needle Time: A Virtuous Cycle

Numerous studies have reported on the phenomenon of an inverse correlation between onset-to-door time and door-to-needle time (153–156). This is thought to be due to physicians treating more urgently those patients who are approaching the end of the thrombolysis time window than patients with earlier presentations (156). Door-to-needle time may be taken as a surrogate global measure of health service-controlled stroke care quality, and given that a personal or family history of cerebrovascular disease and knowledge of thrombolysis are factors associated with early presentation, a scenario can be imagined where improvements in door-to-needle times may, in turn, lead to an improvement in onset-to-door times, supported by the fact that family and friends are a source of stroke knowledge and awareness (129, 138). As patients further recognize the benefits of available acute therapy for stroke, and if in-hospital pathways can be improved so that early presentations are not negated by delayed treatment, a virtuous cycle can be established, in which better onset-to-door and door-to-needle times may further improve each other, leading to a higher proportion of stroke patients arriving within the therapeutic time window for acute stroke therapies.

Toward an Improvement in Onset-to-Door Times

Delayed hospital arrival after acute ischemic stroke is a major factor contributing to low thrombolysis rates. We have reviewed many modifiable factors associated with hospital arrival times, with patient awareness of emergency pathways and the improvement of emergency medical systems being the strongest targets for intervention. Raising the awareness of the varied symptomatology of stroke may also be effective.

Studies on factors associated with prehospital delay after stroke vary widely in their methodology and a more unified approach to this problem and appropriate data collection is warranted. Awareness of stroke represents a key factor, and public education campaigns must be improved and expanded with the view to improve stroke outcomes.

Author Contributions

Both authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript, and the manuscript has not been published elsewhere in whole or in part. Both authors listed have contributed significantly to the project. Contributions specifically were JW to the conception of the project, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript; JP to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer SN and handling editor declared their shared affiliation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bronwyn Gaut for her critical reading of the manuscript.

References

1. Gomez CR. Editorial: time is brain! J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (1993) 3:1–2. doi:10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80125-9

2. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Toni D, Lesaffre E, Von Kummer R, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA (1995) 274:1017–25. doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03530130023023

3. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet (1998) 352:1245–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08020-9

4. Furlan AJ. Endovascular therapy for stroke – it’s about time. N Engl J Med (2015) 372:2347–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1503217

5. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med (2008) 359:1317–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804656

6. Lees KR, Bluhmki E, Von Kummer R, Brott TG, Toni D, Grotta JC, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet (2010) 375:1695–703. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6

7. Evenson KR, Rosamond WD, Morris DL. Prehospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke care. Neuroepidemiology (2001) 20:65–76. doi:10.1159/000054763

8. Evenson KR, Foraker RE, Morris DL, Rosamond WD. A comprehensive review of prehospital and in-hospital delay times in acute stroke care. Int J Stroke (2009) 4:187–99. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00276.x

9. Meretoja A, Strbian D, Mustanoja S, Tatlisumak T, Lindsberg PJ, Kaste M. Reducing in-hospital delay to 20 minutes in stroke thrombolysis. Neurology (2012) 79:306–13. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825d6011

10. Bouckaert M, Lemmens R, Thijs V. Reducing prehospital delay in acute stroke. Nat Rev Neurol (2009) 5:477–83. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.116

11. Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet (2014) 384:1929–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5

12. Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, Del Zoppo GJ. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2014) 7:CD000213. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000213.pub3

13. Badhiwala JH, Nassiri F, Alhazzani W, Selim MH, Farrokhyar F, Spears J, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA (2015) 314:1832–43. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13767

14. Kawano H, Bivard A, Lin L, Ma H, Cheng X, Aviv R, et al. Perfusion computed tomography in patients with stroke thrombolysis. Brain (2017) 140:684–91. doi:10.1093/brain/aww338

15. Libman RB, Wirkowski E, Alvir J, Rao TH. Conditions that mimic stroke in the emergency department. Implications for acute stroke trials. Arch Neurol (1995) 52:1119–22. doi:10.1001/archneur.1995.00540350113023

16. Chernyshev OY, Martin-Schild S, Albright KC, Barreto A, Misra V, Acosta I, et al. Safety of tPA in stroke mimics and neuroimaging-negative cerebral ischemia. Neurology (2010) 74:1340–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dad5a6

17. Arch AE, Weisman DC, Coca S, Nystrom KV, Wira CR III, Schindler JL. Missed ischemic stroke diagnosis in the emergency department by emergency medicine and neurology services. Stroke (2016) 47:668–73. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010613

18. Teuschl Y, Brainin M. Stroke education: discrepancies among factors influencing prehospital delay and stroke knowledge. Int J Stroke (2010) 5:187–208. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00428.x

19. Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, Alonzo A, Croft JB, Dracup K, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation (2006) 114:168–82. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040

20. Alberts MJ, Bertels C, Dawson DV. An analysis of time of presentation after stroke. JAMA (1990) 263:65–8. doi:10.1001/jama.263.1.65

21. Park HA, Ahn KO, Shin SD, Cha WC, Ro YS. The effect of emergency medical service use and inter-hospital transfer on prehospital delay among ischemic stroke patients: a multicenter observational study. J Korean Med Sci (2016) 31:139–46. doi:10.3346/jkms.2016.31.1.139

22. Nazmul Ahasan HAM, Sarkar PK, Das A, Ayaz KFM, Dey P, Siddique AA, et al. Delay in hospital arrival of stroke patients: an observational study. J Med (2013) 14:106–9. doi:10.3329/jom.v14i2.18459

23. Kay R, Woo J, Poon WS. Hospital arrival time after onset of stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1992) 55:973–74. doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.10.973

24. Biller J, Patrick J, Shepard A, Adams H Jr. Delay time between onset of ischemic stroke and hospital arrival. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (1993) 3:228–30. doi:10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80066-7

25. Williams JE, Rosamond WD, Morris DL. Stroke symptom attribution and time to emergency department arrival: the delay in accessing stroke healthcare study. Acad Emerg Med (2000) 7:93–6. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01900.x

26. Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, Hill MD, Buchan AM. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology (2001) 56:1015–20. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.8.1015

27. Misbach J, Ali W. Stroke in Indonesia: a first large prospective hospital-based study of acute stroke in 28 hospitals in Indonesia. J Clin Neurosci (2001) 8:245–9. doi:10.1054/jocn.1999.0667

28. Leopoldino JFS, Fukujima MM, Silva GS, Do Prado GF. Time of presentation of stroke patients in São Paulo Hospital. Arq Neuropsiquiatr (2003) 61:186–7. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2003000200005

29. Koutlas E, Rudolf J, Grivas G, Fitsioris X, Georgiadis G. Factors influencing the pre- and in-hospital management of acute stroke – data from a Greek tertiary care hospital. Eur Neurol (2004) 51:35–7. doi:10.1159/000075084

30. Williams LS, Bruno A, Rouch D, Marriott DJ. Stroke patients’ knowledge of stroke. Influence on time to presentation. Stroke (1997) 28:912–5. doi:10.1161/01.STR.28.5.912

31. Menon SC, Pandey DK, Morgenstern LB. Critical factors determining access to acute stroke care. Neurology (1998) 51:427–32. doi:10.1212/WNL.51.2.427

32. Rosamond WD, Gorton RA, Hinn AR, Hohenhaus SM, Morris DL. Rapid response to stroke symptoms: the Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH) study. Acad Emerg Med (1998) 5:45–51. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02574.x

33. Kothari R, Jauch E, Broderick J, Brott T, Sauerbeck L, Khoury J, et al. Acute stroke: delays to presentation and emergency department evaluation. Ann Emerg Med (1999) 33:3–8. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70431-2

34. Lannehoa Y, Bouget J, Pinel JF, Garnier N, Leblanc JP, Branger B. Analysis of time management in stroke patients in three French emergency departments: from stroke onset to computed tomography scan. Eur J Emerg Med (1999) 6:95–103. doi:10.1097/00063110-199906000-00002

35. Morris DL, Rosamond W, Madden K, Schultz C, Hamilton S. Prehospital and emergency department delays after acute stroke: the Genentech Stroke Presentation Survey. Stroke (2000) 31:2585–90. doi:10.1161/01.STR.31.11.2585

36. Schroeder EB, Rosamond WD, Morris DL, Evenson KR, Hinn AR. Determinants of use of Emergency Medical Services in a population with stroke symptoms: the Second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) Study. Stroke (2000) 31:2591–6. doi:10.1161/01.STR.31.11.2591

37. Lacy CR, Suh DC, Bueno M, Kostis JB. Delay in presentation and evaluation for acute stroke: Stroke Time Registry for Outcomes Knowledge and Epidemiology (S.T.R.O.K.E.). Stroke (2001) 32:63–9. doi:10.1161/01.STR.32.1.63

38. Yoneda Y, Mori E, Uehara T, Yamada O, Tabuchi M. Referral and care for acute ischemic stroke in a Japanese tertiary emergency hospital. Eur J Neurol (2001) 8:483–8. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00275.x

39. Derex L, Adeleine P, Nighoghossian N, Honnorat J, Trouillas P. Factors influencing early admission in a French stroke unit. Stroke (2002) 33:153–9. doi:10.1161/hs0102.100533

40. Harraf F, Sharma AK, Brown MM, Lees KR, Vass RI, Kalra L. A multicentre observational study of presentation and early assessment of acute stroke. BMJ (2002) 325:17. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7354.17

41. Kimura K, Kazui S, Minematsu K, Yamaguchi T; Japan Multicenter Stroke Investigator’s Collaboration. Analysis of 16,922 patients with acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in Japan. A hospital-based prospective registration study. Cerebrovasc Dis (2004) 18:47–56. doi:10.1159/000078749

42. Maze LM, Bakas T. Factors associated with hospital arrival time for stroke patients. J Neurosci Nurs (2004) 36(136–141):155. doi:10.1097/01376517-200406000-00005

43. Rossnagel K, Jungehulsing GJ, Nolte CH, Muller-Nordhorn J, Roll S, Wegscheider K, et al. Out-of-hospital delays in patients with acute stroke. Ann Emerg Med (2004) 44:476–83. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.06.019

44. John M, Palmer P, Faile E, Broce M. Factors causing patients to delay seeking treatment after suffering a stroke. W V Med J (2005) 101:12–5.

45. Turan TN, Hertzberg V, Weiss P, Mcclellan W, Presley R, Krompf K, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with early hospital arrival after stroke symptom onset. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2005) 14:272–7. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2005.07.002

46. Agyeman O, Nedeltchev K, Arnold M, Fischer U, Remonda L, Isenegger J, et al. Time to admission in acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke (2006) 37:963–6. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000206546.76860.6b

47. Barr J, Mckinley S, O’brien E, Herkes G. Patient recognition of and response to symptoms of TIA or stroke. Neuroepidemiology (2006) 26:168–75. doi:10.1159/000091659

48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prehospital and hospital delays after stroke onset – United States, 2005–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (2007) 56:474–8.

49. Inatomi Y, Yonehara T, Hashimoto Y, Hirano T, Uchino M. Pre-hospital delay in the use of intravenous rt-PA for acute ischemic stroke in Japan. J Neurol Sci (2008) 270:127–32. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2008.02.018

50. Maestroni A, Mandelli C, Manganaro D, Zecca B, Rossi P, Monzani V, et al. Factors influencing delay in presentation for acute stroke in an emergency department in Milan, Italy. Emerg Med J (2008) 25:340–5. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.048389

51. Memis S, Tugrul E, Evci ED, Ergin F. Multiple causes for delay in arrival at hospital in acute stroke patients in Aydin, Turkey. BMC Neurol (2008) 8:15. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-8-15

52. Palomeras E, Fossas P, Quintana M, Monteis R, Sebastian M, Fabregas C, et al. Emergency perception and other variables associated with extra-hospital delay in stroke patients in the Maresme region (Spain). Eur J Neurol (2008) 15:329–35. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02082.x

53. Stead LG, Vaidyanathan L, Bellolio MF, Kashyap R, Bhagra A, Gilmore RM, et al. Knowledge of signs, treatment and need for urgent management in patients presenting with an acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a prospective study. Emerg Med J (2008) 25:735–9. doi:10.1136/emj.2008.058206

54. Lichtman JH, Watanabe E, Allen NB, Jones SB, Dostal J, Goldstein LB. Hospital arrival time and intravenous t-PA use in US Academic Medical Centers, 2001–2004. Stroke (2009) 40:3845–50. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.562660

55. Sekoranja L, Griesser AC, Wagner G, Njamnshi AK, Temperli P, Herrmann FR, et al. Factors influencing emergency delays in acute stroke management. Swiss Med Wkly (2009) 139:393–9. doi:10.4414/smw.2009.12506

56. Saver JL, Smith EE, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Zhao X, Olson DM, et al. The “golden hour” and acute brain ischemia: presenting features and lytic therapy in >30,000 patients arriving within 60 minutes of stroke onset. Stroke (2010) 41:1431–9. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583815

57. Gargano JW, Wehner S, Reeves MJ. Presenting symptoms and onset-to-arrival time in patients with acute stroke and transient ischemic attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2011) 20:494–502. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.02.022

58. Kim YS, Park SS, Bae HJ, Cho AH, Cho YJ, Han MK, et al. Stroke awareness decreases prehospital delay after acute ischemic stroke in Korea. BMC Neurol (2011) 11:2. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-2

59. Papapanagiotou P, Iacovidou N, Spengos K, Xanthos T, Zaganas I, Aggelina A, et al. Temporal trends and associated factors for pre-hospital and in-hospital delays of stroke patients over a 16-year period: the Athens study. Cerebrovasc Dis (2011) 31:199–206. doi:10.1159/000321737

60. Iosif C, Papathanasiou M, Staboulis E, Gouliamos A. Social factors influencing hospital arrival time in acute ischemic stroke patients. Neuroradiology (2012) 54:361–7. doi:10.1007/s00234-011-0884-9

61. Jin H, Zhu S, Wei JW, Wang J, Liu M, Wu Y, et al. Factors associated with prehospital delays in the presentation of acute stroke in urban China. Stroke (2012) 43:362–70. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.623512

62. Tong D, Reeves MJ, Hernandez AF, Zhao X, Olson DM, Fonarow GC, et al. Times from symptom onset to hospital arrival in the Get with the Guidelines – Stroke Program 2002 to 2009: temporal trends and implications. Stroke (2012) 43:1912–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.644963

63. Faiz KW, Sundseth A, Thommessen B, Ronning OM. Prehospital delay in acute stroke and TIA. Emerg Med J (2013) 30:669–74. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201543

64. Vidale S, Beghi E, Gerardi F, De Piazza C, Proserpio S, Arnaboldi M, et al. Time to hospital admission and start of treatment in patients with ischemic stroke in northern Italy and predictors of delay. Eur Neurol (2013) 70:349–55. doi:10.1159/000353300

65. Faiz KW, Sundseth A, Thommessen B, Ronning OM. Reasons for low thrombolysis rate in a Norwegian ischemic stroke population. Neurol Sci (2014) 35:1977–82. doi:10.1007/s10072-014-1876-4

66. Hagiwara Y, Imai T, Yamada K, Sakurai K, Atsumi C, Tsuruoka A, et al. Impact of life and family background on delayed presentation to hospital in acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2014) 23:625–9. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.05.034

67. Hsieh MJ, Tang SC, Chiang WC, Huang KY, Chang AM, Ko PC, et al. Utilization of emergency medical service increases chance of thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Formos Med Assoc (2014) 113:813–9. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2013.10.020

68. Yanagida T, Fujimoto S, Inoue T, Suzuki S. Causes of prehospital delay in stroke patients in an urban aging society. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr (2014) 5:77–81. doi:10.1016/j.jcgg.2014.02.001

69. Wongwiangjunt S, Komoltri C, Poungvarin N, Nilanont Y. Stroke awareness and factors influencing hospital arrival time: a prospective observational study. J Med Assoc Thai (2015) 98:260–4.

70. Streifler JY, Davidovitch S, Sendovski U. Factors associated with the time of presentation of acute stroke patients in an Israeli community hospital. Neuroepidemiology (1998) 17:161–6. doi:10.1159/000026168

71. Casetta I, Granieri E, Gilli G, Lauria G, Tola MR, Paolino E. Temporal trend and factors associated with delayed hospital admission of stroke patients. Neuroepidemiology (1999) 18:255–64. doi:10.1159/000026220

72. Goldstein LB, Edwards MG, Wood DP. Delay between stroke onset and emergency department evaluation. Neuroepidemiology (2001) 20:196–200. doi:10.1159/000054787

73. Bohannon RW, Silverman IE, Ahlquist M. Time to emergency department arrival and its determinants in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Conn Med (2003) 67:145–8.

74. Chang KC, Tseng MC, Tan TY. Prehospital delay after acute stroke in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Stroke (2004) 35:700–4. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000117236.90827.17

75. Qureshi AI, Kirmani JF, Sayed MA, Safdar A, Ahmed S, Ferguson R, et al. Time to hospital arrival, use of thrombolytics, and in-hospital outcomes in ischemic stroke. Neurology (2005) 64:2115–20. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000165951.03373.25

76. Majersik JJ, Smith MA, Zahuranec DB, Sanchez BN, Morgenstern LB. Population-based analysis of the impact of expanding the time window for acute stroke treatment. Stroke (2007) 38:3213–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491852

77. Nowacki P, Nowik M, Bajer-Czajkowska A, Porebska A, Zywica A, Nocon D, et al. Patients’ and bystanders’ awareness of stroke and pre-hospital delay after stroke onset: perspectives for thrombolysis in West Pomerania Province, Poland. Eur Neurol (2007) 58:159–65. doi:10.1159/000104717

78. Valiente RA, De Miranda-Alves MA, Silva GS, Gomes DL, Brucki SM, Rocha MS, et al. Clinical features associated with early hospital arrival after acute intracerebral hemorrhage: challenges for new trials. Cerebrovasc Dis (2008) 26:404–8. doi:10.1159/000151681

79. Turin TC, Kita Y, Rumana N, Takashima N, Ichikawa M, Sugihara H, et al. The time interval window between stroke onset and hospitalization and its related factors. Neuroepidemiology (2009) 33:240–6. doi:10.1159/000229778

80. Puolakka T, Vayrynen T, Happola O, Soinne L, Kuisma M, Lindsberg PJ. Sequential analysis of pretreatment delays in stroke thrombolysis. Acad Emerg Med (2010) 17:965–9. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00828.x

81. Fang J, Yan W, Jiang GX, Li W, Cheng Q. Time interval between stroke onset and hospital arrival in acute ischemic stroke patients in Shanghai, China. Clin Neurol Neurosurg (2011) 113:85–8. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.09.004

82. Addo J, Ayis S, Leon J, Rudd AG, Mckevitt C, Wolfe CD. Delay in presentation after an acute stroke in a multiethnic population in South London: the South London Stroke Register. J Am Heart Assoc (2012) 1:e001685. doi:10.1161/JAHA.112.001685

83. Eleonora I, Patrizia N, Ilaria R, Alessandra Del B, Francesco A, Benedetta P, et al. Delay in presentation after acute ischemic stroke: the Careggi Hospital Stroke Registry. Neurol Sci (2014) 35:49–52. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1484-8

84. Ming L, Fisher M, Guanggu Y, Hongbo Z. Early presentation of acute stroke in a Chinese population. Cerebrovasc Dis (1995) 5:362–5. doi:10.1159/000107883

85. Fogelholm R, Murros K, Rissanen A, Ilmavirta M. Factors delaying hospital admission after acute stroke. Stroke (1996) 27:398–400. doi:10.1161/01.STR.27.3.398

86. Pistollato G, Ermani M. Time of hospital presentation after stroke. A multicenter study in north-east Italy. Italian SINV (Societa Interdisciplinare Neurovascolare) Study group. Ital J Neurol Sci (1996) 17:401–7. doi:10.1007/BF01997714

87. Moulin T, Tatu L, Crepin-Leblond T, Chavot D, Berges S, Rumbach T. The Besancon Stroke Registry: an acute stroke registry of 2,500 consecutive patients. Eur Neurol (1997) 38:10–20. doi:10.1159/000112896

88. Smith MA, Doliszny KM, Shahar E, Mcgovern PG, Arnett DK, Luepker RV. Delayed hospital arrival for acute stroke: the Minnesota Stroke Survey. Ann Intern Med (1998) 129:190–6. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00005

89. Yip PK, Jeng JS, Lu CJ. Hospital arrival time after onset of different types of stroke in greater Taipei. J Formos Med Assoc (2000) 99:532–7.

90. Salisbury HR, Banks BJ, Footitt DR, Winner SJ, Reynolds DJ. Delay in presentation of patients with acute stroke to hospital in Oxford. QJM (1998) 91:635–40. doi:10.1093/qjmed/91.9.635

91. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Hui AC, Leung CS, Wong KS. Influence of emergency room fee on acute stroke presentation in a public hospital in Hong Kong. Neuroepidemiology (2004) 23:123–8. doi:10.1159/000075955

92. Iguchi Y, Wada K, Shibazaki K, Inoue T, Ueno Y, Yamashita S, et al. First impression at stroke onset plays an important role in early hospital arrival. Intern Med (2006) 45:447–51. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1554

93. Tanaka Y, Nakajima M, Hirano T, Uchino M. Factors influencing pre-hospital delay after ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Intern Med (2009) 48:1739–44. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2378

94. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Factors delaying hospital admission in acute stroke: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Neurology (1996) 47:383–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.47.2.383

95. Pittock SJ, Meldrum D, Hardiman O, Deane C, Dunne P, Hussey A, et al. Patient and hospital delays in acute ischaemic stroke in a Dublin teaching hospital. Ir Med J (2003) 96:167–8.

96. Leon-Jimenez C, Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Chiquete E, Vega-Arroyo M, Arauz A, Murillo-Bonilla LM, et al. Hospital arrival time and functional outcome after acute ischaemic stroke: results from the PREMIER study. Neurologia (2014) 29:200–9. doi:10.1016/j.nrl.2013.05.003

97. Hong ES, Kim SH, Kim WY, Ahn R, Hong JS. Factors associated with prehospital delay in acute stroke. Emerg Med J (2011) 28:790–3. doi:10.1136/emj.2010.094425

98. Koksal EK, Gazioglu S, Boz C, Can G, Alioglu Z. Factors associated with early hospital arrival in acute ischemic stroke patients. Neurol Sci (2014) 35:1567–72. doi:10.1007/s10072-014-1796-3

99. Mandelzweig L, Goldbourt U, Boyko V, Tanne D. Perceptual, social, and behavioral factors associated with delays in seeking medical care in patients with symptoms of acute stroke. Stroke (2006) 37:1248–53. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000217200.61167.39

100. Geffner D, Soriano C, Perez T, Vilar C, Rodriguez D. Delay in seeking treatment by patients with stroke: who decides, where they go, and how long it takes. Clin Neurol Neurosurg (2012) 114:21–5. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.08.014

101. Ashraf VV, Maneesh M, Praveenkumar R, Saifudheen K, Girija AS. Factors delaying hospital arrival of patients with acute stroke. Ann Indian Acad Neurol (2015) 18:162–6. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.150627

102. Pandian JD, Kalra G, Jaison A, Deepak SS, Shamsher S, Padala S, et al. Factors delaying admission to a hospital-based stroke unit in India. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2006) 15:81–7. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2006.01.001

103. Korkmaz T, Ersoy G, Kutluk K, Erbil B, Karbek Akarca F, Sönmez N. An evaluation of pre-admission factors affecting the admission time of patients with stroke symptoms. Turk J Emerg Med (2010) 10:106–11.

104. Barsan WG, Brott TG, Broderick JP, Haley EC, Levy DE, Marler JR. Time of hospital presentation in patients with acute stroke. Arch Intern Med (1993) 153:2558–61. doi:10.1001/archinte.153.22.2558

105. Ritter MA, Brach S, Rogalewski A, Dittrich R, Dziewas R, Weltermann B, et al. Discrepancy between theoretical knowledge and real action in acute stroke: self-assessment as an important predictor of time to admission. Neurol Res (2007) 29:476–9. doi:10.1179/016164107X163202

106. Eissa A, Krass I, Levi C, Sturm J, Ibrahim R, Bajorek B. Understanding the reasons behind the low utilisation of thrombolysis in stroke. Australas Med J (2013) 6:152–63. doi:10.4066/AMJ.2013.1607

107. Soomann M, Vibo R, Korv J. Acute stroke: why do some patients arrive in time and others do not? Eur J Emerg Med (2015) 22:285–7. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000206

108. Herderscheê D, Limburg M, Hijdra A, Bollen A, Pluvier J, Te Water W. Timing of hospital admission in a prospective series of stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis (1991) 1:165–7. doi:10.1159/000108835

109. Kamal AK, Khealani BA, Ansari SA, Afridi M, Syed NA. Early ischemic stroke presentation in Pakistan. Can J Neurol Sci (2009) 36:181–6. doi:10.1017/S0317167100006545

110. Kaneko C, Goto A, Watanabe K, Yasumura S. Time to presenting to hospital and associated factors in stroke patients. A hospital-based study in Japan. Swiss Med Wkly (2011) 141:w13296. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13296

111. Sreedharan SE, Ravindran J. Barriers to thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: experience from a level 1 hospital in South Australia. Neurol Asia (2011) 16:17–23.

112. Ferro JM, Melo TP, Oliveira V, Crespo M, Canhão P, Pinto AN. An analysis of the admission delay of acute strokes. Cerebrovasc Dis (1994) 4:72–5. doi:10.1159/000108455

113. Wester P, Radberg J, Lundgren B, Peltonen M. Factors associated with delayed admission to hospital and in-hospital delays in acute stroke and TIA: a prospective, multicenter study. Seek-Medical-Attention-in-Time Study Group. Stroke (1999) 30:40–8. doi:10.1161/01.STR.30.1.40

114. Srivastava AK, Prasad K. A study of factors delaying hospital arrival of patients with acute stroke. Neurol India (2001) 49:272–6.

115. Tan TY, Chang KC, Liou CW. Factors delaying hospital arrival after acute stroke in southern Taiwan. Chang Gung Med J (2002) 25:458–63.

116. De Silva DA, Ong SH, Elumbra D, Wong MC, Chen CL, Chang HM. Timing of hospital presentation after acute cerebral infarction and patients’ acceptance of intravenous thrombolysis. Ann Acad Med Singapore (2007) 36:244–6.

117. Siddiqui M, Siddiqui SR, Zafar A, Khan FS. Factors delaying hospital arrival of patients with acute stroke. J Pak Med Assoc (2008) 58:178–82.

118. Curran C, Henry C, O’connor KA, Cotter PE. Predictors of early arrival at the emergency department in acute ischaemic stroke. Ir J Med Sci (2011) 180:401–5. doi:10.1007/s11845-011-0686-4

119. Kozera G, Chwojnicki K, Gojska-Grymajlo A, Gasecki D, Schminke U, Nyka WM, et al. Pre-hospital delays and intravenous thrombolysis in urban and rural areas. Acta Neurol Scand (2012) 126:171–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01616.x

120. Lin CS, Tsai J, Woo P, Chang H. Prehospital delay and emergency department management of ischemic stroke patients in Taiwan, R.O.C. Prehosp Emerg Care (1999) 3:194–200. doi:10.1080/10903129908958936

121. Kim HJ, Ahn JH, Kim SH, Hong ES. Factors associated with prehospital delay for acute stroke in Ulsan, Korea. J Emerg Med (2011) 41:59–63. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.04.001

122. Harper GD, Haigh RA, Potter JF, Castleden CM. Factors delaying hospital admission after stroke in Leicestershire. Stroke (1992) 23:835–8. doi:10.1161/01.STR.23.6.835

123. Ellis C, Knapp RG, Gilbert GE, Egede LE. Factors associated with delays in seeking treatment for stroke care in veterans. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2013) 22:e136–41. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.09.017

124. Siegler JE, Boehme AK, Albright KC, Martin-Schild S. Ethnic disparities trump other risk factors in determining delay to emergency department arrival in acute ischemic stroke. Ethn Dis (2013) 23:29–34.

125. Azzimondi G, Bassein L, Fiorani L, Nonino F, Montaguti U, Celin D, et al. Variables associated with hospital arrival time after stroke: effect of delay on the clinical efficiency of early treatment. Stroke (1997) 28:537–42. doi:10.1161/01.STR.28.3.537

126. Chen CH, Huang P, Yang YH, Liu CK, Lin TJ, Lin RT. Pre-hospital and in-hospital delays after onset of acute ischemic stroke: a hospital-based study in southern Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci (2007) 23:552–9. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70002-0

127. Broadley SA, Thompson PD. Time to hospital admission for acute stroke: an observational study. Med J Aust (2003) 178:329–31.

128. Zerwic J, Hwang SY, Tucco L. Interpretation of symptoms and delay in seeking treatment by patients who have had a stroke: exploratory study. Heart Lung (2007) 36:25–34. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.12.007

129. Jones SP, Jenkinson AJ, Leathley MJ, Watkins CL. Stroke knowledge and awareness: an integrative review of the evidence. Age Ageing (2010) 39:11–22. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp196

130. Wein TH, Staub L, Felberg R, Hickenbottom SL, Chan W, Grotta JC, et al. Activation of Emergency Medical Services for acute stroke in a nonurban population: the T.L.L. Temple Foundation Stroke Project. Stroke (2000) 31:1925–8. doi:10.1161/01.STR.31.8.1925

131. Morgenstern LB, Staub L, Chan W, Wein TH, Bartholomew LK, King M, et al. Improving delivery of acute stroke therapy: the TLL Temple Foundation Stroke Project. Stroke (2002) 33:160–6. doi:10.1161/hs0102.101990

132. Baldereschi M, Piccardi B, Di Carlo A, Lucente G, Guidetti D, Consoli D, et al. Relevance of prehospital stroke code activation for acute treatment measures in stroke care: a review. Cerebrovasc Dis (2012) 34:182–90. doi:10.1159/000341856

133. Ekundayo OJ, Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH, Xian Y, Zhao X, et al. Patterns of Emergency Medical Services use and its association with timely stroke treatment: findings from Get With the Guidelines-Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes (2013) 6:262–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000089

134. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Acute stroke with atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke (1996) 27:1765–9. doi:10.1161/01.STR.27.10.1765

135. Wolf PA. Awareness of the role of atrial fibrillation as a cause of ischemic stroke. Stroke (2014) 45:e19–21. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003282

136. Jorgensen H, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Stroke in patients with diabetes. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke (1994) 25:1977–84. doi:10.1161/01.STR.25.10.1977

137. Megherbi SE, Milan C, Minier D, Couvreur G, Osseby GV, Tilling K, et al. Association between diabetes and stroke subtype on survival and functional outcome 3 months after stroke: data from the European BIOMED Stroke Project. Stroke (2003) 34:688–94. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000057975.15221.40

138. Pancioli AM, Broderick J, Kothari R, Brott T, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, et al. Public perception of stroke warning signs and knowledge of potential risk factors. JAMA (1998) 279:1288–92. doi:10.1001/jama.279.16.1288

139. Keskin O, Kalemoglu M, Ulusoy RE. A clinic investigation into prehospital and emergency department delays in acute stroke care. Med Princ Pract (2005) 14:408–12. doi:10.1159/000088114

140. Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Broderick JP, Rademacher E, Woo D, Flaherty ML, et al. Temporal trends in public awareness of stroke: warning signs, risk factors, and treatment. Stroke (2009) 40:2502–6. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551861

141. De Silva DA, Yassin N, Toh AJ, Lim DJ, Wong WX, Woon FP, et al. Timing of arrival to a tertiary hospital after acute ischaemic stroke – a follow-up survey 5 years later. Ann Acad Med Singapore (2010) 39:513–5.

142. Coutinho JM, Klaver EC, Roos YB, Stam J, Nederkoorn PJ. Ethnicity and thrombolysis in ischemic stroke: a hospital based study in Amsterdam. BMC Neurol (2011) 11:81. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-81

143. Sug Yoon S, Heller RF, Levi C, Wiggers J, Fitzgerald PE. Knowledge of stroke risk factors, warning symptoms, and treatment among an Australian urban population. Stroke (2001) 32:1926–30. doi:10.1161/01.STR.32.8.1926

144. Cheung RT. Hong Kong patients’ knowledge of stroke does not influence time-to-hospital presentation. J Clin Neurosci (2001) 8:311–4. doi:10.1054/jocn.2000.0805

145. Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Bonikowski F, Morgenstern LB. The role of ethnicity, sex, and language on delay to hospital arrival for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke (2010) 41:905–9. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578112

146. Petrea RE, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Kelly-Hayes M, Kase CS, Wolf PA. Gender differences in stroke incidence and poststroke disability in the Framingham heart study. Stroke (2009) 40:1032–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542894

147. Di Carlo A, Lamassa M, Baldereschi M, Pracucci G, Basile AM, Wolfe CD, et al. Sex differences in the clinical presentation, resource use, and 3-month outcome of acute stroke in Europe: data from a multicenter multinational hospital-based registry. Stroke (2003) 34:1114–9. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000068410.07397.D7

148. Kapral MK, Fang J, Hill MD, Silver F, Richards J, Jaigobin C, et al. Sex differences in stroke care and outcomes: results from the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Stroke (2005) 36:809–14. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000157662.09551.e5

149. Lisabeth LD, Brown DL, Hughes R, Majersik JJ, Morgenstern LB. Acute stroke symptoms: comparing women and men. Stroke (2009) 40:2031–6. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.546812

150. Stuart-Shor EM, Wellenius GA, Delloiacono DM, Mittleman MA. Gender differences in presenting and prodromal stroke symptoms. Stroke (2009) 40:1121–6. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543371

151. Knauft W, Chhabra J, Mccullough LD. Emergency department arrival times, treatment, and functional recovery in women with acute ischemic stroke. J Womens Health (2010) 19:681–8. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1616

152. Silvestrelli G, Parnetti L, Tambasco N, Corea F, Capocchi G; Perugia Stroke and Neuroradiology Team. Characteristics of delayed admission to stroke unit. Clin Exp Hypertens (2006) 28:405–11. doi:10.1080/10641960600549892

153. Romano JG, Muller N, Merino JG, Forteza AM, Koch S, Rabinstein AA. In-hospital delays to stroke thrombolysis: paradoxical effect of early arrival. Neurol Res (2007) 29:664–6. doi:10.1179/016164107X240035

154. Ferrari J, Knoflach M, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Matosevic B, Seyfang L, et al. Stroke thrombolysis: having more time translates into delayed therapy: data from the Austrian Stroke Unit Registry. Stroke (2010) 41:2001–4. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.590372

155. Mikulik R, Kadlecova P, Czlonkowska A, Kobayashi A, Brozman M, Svigelj V, et al. Factors influencing in-hospital delay in treatment with intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke (2012) 43:1578–83. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.644120

Keywords: stroke, prehospital delay, thrombolysis, tissue plasminogen activator, emergency medical services

Citation: Pulvers JN and Watson JDG (2017) If Time Is Brain Where Is the Improvement in Prehospital Time after Stroke? Front. Neurol. 8:617. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00617

Received: 30 July 2017; Accepted: 06 November 2017;

Published: 20 November 2017

Edited by:

Tracey Weiland, University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Sandra Leanne Neate, University of Melbourne, AustraliaDaniel Fatovich, University of Western Australia, Australia

Mark William Parsons, University of Newcastle, Australia

Copyright: © 2017 Pulvers and Watson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John D. G. Watson, john.watson@sydney.edu.au

Jeremy N. Pulvers

Jeremy N. Pulvers John D. G. Watson

John D. G. Watson