Populism Against Europe in Social Media: The Eurosceptic Discourse on Twitter in Spain, Italy, France, and United Kingdom During the Campaign of the 2019 European Parliament Election

- Department of Communication Sciences, Universitat Jaume I, Castellón de la Plana, Spain

Since its inception, the European Union has been facing several challenges. The economic and refugee crises, along with the results of the British referendum, have shaped the future of Europe in the past decade. These challenges among others have encouraged the emergence of populist parties, which aim at disrupting the current status quo posing threats to democracy. In this context, the consolidation of digital media has played a key role in the circulation of populist messages to a large number of people. Such messages have questioned the political and legitimacy terms of the European Union, leading to the ideal scenario of Euroscepticism. This article examines the framing and communication strategies used by the European populist actors regarding the European Union and Euroscepticism. The aim is to identify if there are any significant ideological differences. The sample consists of the shared messages (n = 3,667) by the main European populist political parties of Spain, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom during the European Parliament election campaign in 2019. The messages published on the Twitter accounts of Podemos, Vox, the 5 Star Movement, Lega, Rassemblement National, France Insoumise, The Brexit Party, and the UKIP have been analyzed. Results show that two types of Eurosceptic discourse were detected depending on the ideology. The right-wing populists pose a Euroscepticism exclusionary discourse, based on the loss of sovereignty and the distinction of “they”—“us,” excluding the out-groups whereas the left-wing populists present a Euroscepticism inclusive discourse, to maintain the foundational values of Europe, such as equality or solidarity between different people and countries. This research found that Eurosceptic discourse is used in the communicative strategy of populist political parties on Twitter and highlights the importance of the message frame which makes the difference about it.

Introduction

The electoral success of several populist political parties has increased the news coverage along with the academic interest in populism. In Italy, the 5 Star Movement was the most voted political option in the 2018 elections and ended up ruling with the Liga (Chiaramonte et al., 2018). In France, in the 2017 presidential elections, the National Front obtained 7.5 million votes and made it to the second round, something that had never happened before (Ivaldi, 2018). In Spain, Podemos emerged in the 2014 European elections, consolidating its political strength by winning 79 seats in the Spanish Parliament in 2016 (Casero-Ripollés et al., 2016). In Britain, the UKIP advocated the celebration of Brexit, a referendum the purpose of which was to leave the European Union (Usherwood, 2019).

Populism is a varied phenomenon. This fact makes it an interesting topic to explore within the European context. There are differences regarding populism ideology. In particular, there are differences in its political–historical development or its programmatic proposals. Not only differences regarding populism ideology can be found, but also concerning their political trajectory or their programmatic proposals (Caiani and Graziano, 2016). There are different approaches to study the populism. Some authors consider it a form of political organization based on the presence of a charismatic leader who raises his government with the direct support of the people (Taggart, 2000; Weyland, 2001). Others consider it a communicative style (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; Bos et al., 2010, 2011; Moffitt, 2016; Block and Negrine, 2017). Populism has also been defined as a way to construct the political (Laclau, 2005; Hawkins, 2010) and as a set of ideas (Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart, 2016; Rooduijn and Akkerman, 2017). However, a large number of researchers define populism as a thin-centered ideology (Canovan, 2002; Abts and Rummens, 2007; Mudde, 2007; Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008; Aalberg and de Vreese, 2017). That is to say, a moldable ideology that can be adapted to a multitude of contexts and that considers that society is divided into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, the pure people and the corrupt elite, and that maintains that politics should be the expression of the general will (Mudde, 2004).

Despite being a difficult concept to define, populism has undoubtedly marked the political debate of recent decades. For this reason, some authors argue that Western democracies are immersed in a populist Zeitgeist (Mudde, 2004). That is, we are immersed in a populist period dominated by the emergence and development of new populist movements, both left, and right-wing. These movements want to break the status quo that has prevailed up to the present (Gerbaudo, 2018) and take advantage of the political opportunity structure to do it (Hall, 2000). In this context, popular sovereignty functions as a link between left-wing and right-wing populist political actors (Gerbaudo, 2017). In both cases, they seek to regain control of their territory and restore the loss of autonomy in an extremely globalized world, in which membership in supranational organizations such as the European Union, deprives them of the ability to legislate in their own countries. In this sense, some populist political actors consider borders to be essential to maintain sovereignty (Wallerstein, 2004) since in their fight against the establishment is the only way to reclaim popular sovereignty (Rooduijn, 2014; Hameleers, 2018). According to Butler (2014), popular sovereignty is an act of self-assignment carried out by the people and is not linked to any political authority or regime. In this context, the idea of sovereignty, in any of its forms, falls on a precarious process of citizens, an aspect that reinforces the demand for hard physical and cultural borders, exposing their vulnerability (Lorey, 2015).

The rise of populism in European democracies have escalated due to the economic crisis, the refugee crisis and the results of the British referendum. In the debate generated around Brexit, there was already talk of the need to establish borders and create tough immigration policies so as not to undermine the well-being of the British people, building the idea of sovereignty around precariousness and xenophobia (Pencheva and Maronitis, 2018). All these events have affected the future of Europe during the last decade (Bergbauer et al., 2019). These crises have intensified the level of partisan competition in European elections, aggravating the level of politicization of European affairs and increasing the level of pessimism among voters, and paved the way for the emergence of an ideal scenario for Eurosceptic political actors (Ivaldi, 2018), that oppose the principles, institutions or policies legislated in the European Union (Leconte, 2010). This is an especially favorable context for the radical-right populist parties, who base their communicative strategy on questioning the functioning of the European Union as we know it today.

In addition, Europe has suffered a crisis of values that caused many citizens to question several defining elements of the European Union and even the permanence in it. This aspect is included in the manifestos of a large number of the populist parties (Vasilopoulou, 2018). According to Mudde (2007), populist parties are not against the founding principles of the European Union, but against those who manage the institution. In other words, Euroscepticism translates into criticism of certain policies promoted by the European Union, but not in reprobating the institution itself. In that sense, we can make a distinction between the different economic and social dimensions of Euroscepticism (van Klingeren et al., 2013) as, for example, economic Euroscepticism, common among left and right populists (van Elsas et al., 2016), or cultural Euroscepticism that can focus on the national sovereignty (Mammone, 2009; Gerbaudo, 2017, 2018) or the distinction between us and them in reference to immigrants (Kriesi, 2007; Leconte, 2010; Wodak, 2015; Fuchs, 2017). However, some authors argue that both dimensions of Euroscepticism are interconnected (McLaren, 2006). Taggart and Szczerbiak (2002) discern between “soft” and “hard” forms of Euroscepticism. In this context, the opposition to the European Union policies is considered a “soft” form, meanwhile opposition to the process of European integration itself is regarded as a “hard” form of Euroscepticism.

In this context, as with other actors outside the establishment, such as social movements (Casero-Ripollés and Feenstra, 2012; Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés, 2016), some authors believe that the success of populism is related to its communicative strategy (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; Casero-Ripollés et al., 2017; Engesser et al., 2017a; de Vreese et al., 2018). Populist political parties depend more on the media than the consolidated ones due to their weak organization (Aalberg and de Vreese, 2017). In the 1990s, the most widely medium used by populist political options to spread its messages was television (Mazzoleni, 2008). In general, they took advantage of the coverage of the sensationalist media to obtain more visibility and increase their number of voters (Mazzoleni, 2003). However, social media is nowadays a powerful tool for them, since they can communicate directly with their followers and mobilize them (Bartlett et al., 2011). This way, they can spread their messages to a large number of users with a click (Kriesi, 2014).

Twitter has become the reference platform for political actors among social media. According to the study made by Burson-Marsteller (2018), 97% of world leaders have an account on this social media, 4 points above Facebook and 16 more than Instagram. Thus, Twitter has become an essential channel for populist political actors since allows them to communicate with the people quickly, easily and directly (Esser et al., 2017), as well as setting up their agenda and frames (Gainous and Wagner, 2014; Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés, 2018; Alonso-Muñoz, 2019).

For this reason, the following research questions have been posed:

RQ1. Is Euroscepticism present in the communicative strategies of populist political actors on Twitter regardless of their ideology?

RQ2. Are there differences in the way of framing messages related to the European political project on Twitter based on the ideology of populist political parties?

Data and Methods

To know the framing and communication strategies used by the European populist actors regarding the European Union and Euroscepticism, a qualitative analysis method has been used. On the one hand, critical discourse analysis is applied (Wodak and Meyer, 2003; van Dijk, 2012; Flesher Fominaya, 2015). This type of analysis understands discourse as a form of symbolic power. In this context, discourse is considered to be a great conditioner of public opinion and, therefore, a key tool in the social construction of reality (van Dijk, 2006). In addition, to know under which parameters the messages about the European Union were framed, the study on framing by Entman (1993) has been used. This study establishes four basic functions: (1) definition of the problem: determine what a causal agent is doing, (2) attribution of responsibilities: identify the forces creating the problem, (3) moral assessment: evaluate causal agents and their effect, and (4) possible solution: offer and justify treatments for the problems.

The sample of this research is composed of messages posted on Twitter by eight European populist political parties during the campaign of the European Parliament elections held in May 2019. Given that the elections were not held on the same day in all countries, and that the beginning of the campaign was not the same for everyone, it has been decided to analyze all the messages published between May 1 and 31, 2019. In particular, tweets published by Podemos and Vox (Spain), the 5 Star Movement and the Lega (Italy), Rassemblement National and France Insoumise (France), and the UKIP and The Brexit Party (United Kingdom) have been analyzed. The choice of the sample responds to the fact that they are parties from four similar countries in terms of size and political relevance in Europe. In addition, according to data published by the International Monetary Fund, France, United Kingdom, Italy and Spain are four of the main European world powers.

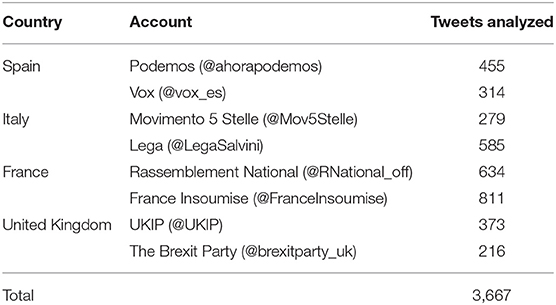

Tweets have been downloaded using the Twitonomy web application, which in its premium version allows downloading tweets, retweets and replies from the selected Twitter accounts. A total amount of 12,104 messages were collected, of which 3,667 were analyzed, including both tweets and replies (Table 1). Retweets have not been studied in this research as they are useless to help achieve the objective of this research, which focuses on the creation of discourse and not on the strategy of content circulation.

Results

Contextual Sphere: The Opportunity Structure of Populist Political Actors

As with other actors, the success of populist political actors is closely related to both political and discursive opportunity structures. The political opportunity structure (POS) refers to the conditions of the political environment that offer incentives for actors who are not part of the establishment, such as social movements, to participate in political decision-making (Tarrow, 1994; Kriesi, 1995). In this regard, Gamson (2004, p. 249) adds that the POS is “the playing field where the context is set.” On the other hand, the discursive opportunity structure (DOS) determines the possibilities of a message to be disseminated in the public sphere (Koopmans and Olzak, 2004). Specifically, visibility—depending on the number of channels in which it is disseminated—the impact understood as the degree of reactions generated by a message, and legitimacy—determined by the degree of positive reactions—are the three most determining characteristics for a message to be successful (Koopmans and Olzak, 2004). This implies that the socio-political context has an important influence on the triumph or failure of the actions carried out by populist actors. Likewise, the context also has an impact in discursive terms as it can condition the decoding of a message since the understanding of a subject by citizens is determined by the context in which it is received (van Dijk, 2003, 2006).

The 2019 European Parliament Elections were held in a context of strong political disaffection. According to data from Standard Eurobarometer 90 (2018), 48% of Europeans were not interested in those elections. In addition, the citizens surveyed indicated, both before and after the elections were held, that some of their main concerns regarding the European Union were immigration (40% in 2018 and 34% in 2019), terrorism (19% in 2018 and 18% in 2019) and the economic situation (18% in both periods) (Eurobarometer, 20181, 20192). Thus, the economic crisis, the refugee crisis and the results of the British referendum have been affecting the future of Europe during the last decade. These events have intensified the level of partisan competition in the European elections, aggravating the level of politicization of European affairs and increasing the level of pessimism among voters, creating an ideal scenario for Eurosceptic political actors (Ivaldi, 2018). In this context, the 2019 European elections were held, which were characterized by the rise of populist parties, especially those of the extreme right, who conducted an electoral campaign based on Euroscepticism and the idea that the European Union as we know it doesn't work.

In addition to using the POS and the DOS, Engesser et al. (2017a) consider that populism also uses the online opportunity structure. This means that populism thrives on the inherent values within the digital media system to promote communication.

Conventional media, such as television, press, and radio, offer political actors a form of contact with citizens (Krämer, 2014). However, it is very difficult for populist actors to pass the filter of journalists and release their messages without restrictions (Shoemaker and Vos, 2009). Web 2.0 and social media, on the other hand, allow them to circumvent conventional media (Atton, 2006; Bartlett et al., 2011; Groshek and Engelbert, 2013; Casero-Ripollés et al., 2017; Engesser et al., 2017a), making it easier for their messages to reach citizens directly (Bennett and Manheim, 2006; Vaccari and Valeriani, 2015). Populist politicians capitalize on the power and influence of social media in the formation of citizen opinions by disseminating populist ideas, such as the elite attack or the defense of the people (Engesser et al., 2017b). Gerbaudo (2014) branded this phenomenon “Populism 2.0.”

In this regard, some authors recognize that homophilia is cultivated in the digital environment. In other words, different individuals who have the same political views or similar beliefs and thoughts create bonds (Colleoni et al., 2014; Guerrero-Solé, 2018). This is another factor that favors the communication of populist actors, together with the fact that the internet and social media function as an echo chamber for the political elites as exclusively their ideas become relevant (Jackson and Lilleker, 2011; Verweij, 2012; Graham et al., 2013), while the dissonant voices are relegated to other spheres. Using these characteristics, they can ratify and amplify the messages that go against those groups or minorities that, according to these actors, have no place in society and, therefore, are not part of the people (Sunstein, 2001; Jamieson and Cappella, 2008).

Discursive Sphere: Discursive Strategy of Populist Political Actors

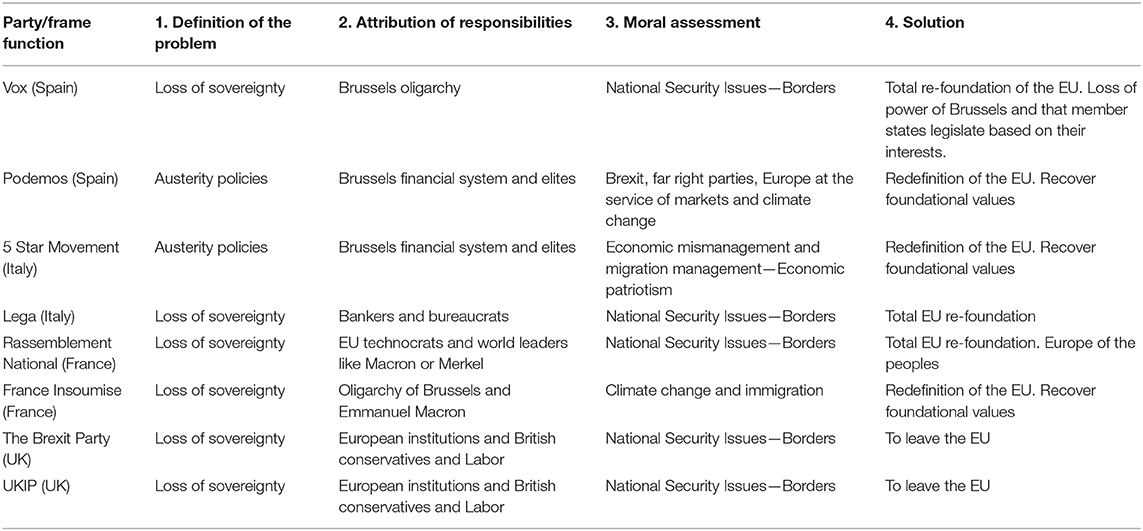

The analysis of the messages published on the Twitter accounts of the selected political parties indicates that their communicative strategy in this social media platform is articulated around the four functions of framing defined by Entman (1993): definition of the problem, attribution of responsibilities, moral assessment of the facts, and approach to a solution.

Spain: Vox and Podemos

In Spain, European, regional and municipal elections were held on the same day. In this regard, during May 2019, the period analyzed, both Vox and Podemos prioritized the publication of messages concerning national policy on their Twitter accounts rather than presenting European proposals.

Vox's discourse regarding the European project on Twitter highlights that the main problem of belonging to a supranational organization such as the European Union is the loss of national sovereignty. In this regard, they allege that “Spain cannot limit itself to be a province of Brussels” and that the European Union is “taking away powers that correspond to the sovereign states.” In addition, they argue that Spanish sovereignty cannot be questioned by the rest of member states, something that the president of the Spanish government must watch over. The Spanish right-wing populist party emphasizes that the culprits of this situation are the heads of state of certain Member States, such as Angela Merkel (Germany) or Emmanuel Macron (France), who are only looking for their interests, and not for those of the whole of the European Union. This is what Vox calls the “oligarchy of Brussels.” In this context, Vox raises a discourse based on the differentiation between us, the people, and them, the Brussels elite that oppresses the sovereign people.

Among the consequences of the loss of sovereignty, Vox highlights the fact that member states are forced to open their borders for free movement of people, an aspect they disagree with, given that they openly oppose immigration. In this regard, when referring to the current refugee crisis in Europe, the candidate for the European elections, Jorge Buxadé, argues that the first thing is to check whether all migrants trying to enter Europe are indeed refugees. Therefore, it is essential that every member state develop asylum policies, each establishing its criteria and conditions to enter and remain in the country.

For Vox, the solution is to “stand up to the oligarchy of Brussels” and carry out a “comprehensive reform” of Europe, a total re-foundation to take power away from Brussels and give it back to the member states of the European Union. Against those who propose the federalization of Europe, Vox defends a European Union in which the states decide for themselves and legislate considering their interests. Thus, nations must cooperate freely and not receive Brussels guidelines. In this regard, they provide the case of Carles Puigdemont as an example. The former president of the Generalitat de Catalunya fled from Spain to Belgium after the celebration of the independence referendum and the proclamation, and subsequent suspense, of the Catalan Republic. Vox considers that Spain has been harmed by Brussels inferences as they allowed Puigdemont, whom they branded as “the coup leader” to become a “refugee for the European authorities.” In this sense, they strongly criticize the euro order system that exists today. Vox argues that Europe should not question the justice of one of its member states, as a German court did after ruling that the facts that justified Puigdemont's request for surrender by rebellion did not entail such a crime in Germany.

For Podemos, on the other hand, all the problems that Europe suffers are a consequence of the strong crisis that the European model is suffering today. Specifically, the Spanish left-wing populist party, in its communication strategy on Twitter, considers that the austerity policies demanded by the European Union have caused a strong crisis of the social model, have weakened the political parties and have generated a strong territorial crisis causing confrontation among the different states that conform the European Union.

In this sense, Podemos blames austerity policies promoted by the European Parliament for everything that is happening in Europe right now since they have proved to be “highly ineffective” as they have impoverished citizens. Thus, they argue that both Brexit and the emergence of the extreme right are both the result of “austerity” economic policies and the mismanagement of the refugee crisis.

Therefore, against those who intend to keep current Europe at the service of markets such as Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron, Podemos wants a Europe that defends the rights of citizens. Although dissatisfied with the functioning of the institution, they argue that the solution is the redefinition of the European Union to provide citizens a more relevant role so that they can be part of the decision-making process that affects them so much. For this reason, they are defined as “Eurocritics” as oppose to “Eurosceptics” who are represented by figures like Mateo Salvini or Victor Orban. In this sense, Podemos is running a campaign to try to mobilize the left-wing electorate to stop the extreme right and to prevent it from conquering Europe.

To face all the problems that the European Union is experiencing, it is necessary to take action to recover its foundational values: democracy, peace, freedom and solidarity among States. Only by voting left, “can we build a Europe of the peoples, made of solidarity, antifascist, democratic, feminist, with rights for all, and with an economy that does not leave anybody behind.” To achieve a “fairer Europe,” they present on Twitter a decalogue of actions that focused on two issues: climate change and immigration. Using the slogan “there is no spare planet,” they advocate the creation of a “conscious and environmentalist Europe that actively fights against climate change.” According to the argument on Twitter of Podemos, for this to be possible the decisions taken in Europe must not respond to economic lobbies, but the good of citizens. Regarding immigration, they establish that it is necessary “to build bridges, not walls.” For this, it is essential “to create legal and safe ways for migrants” to migrate without putting their lives at risk as happens with those who try to cross the Mediterranean Sea daily and lose their lives. It is also necessary to end the “hot returns” as happens in Spain with those migrants who try to cross the fence that separates Spain from Morocco, since it threatens the human rights defined by the United Nations Organization (UN). As well as ending the criminalization of migrants and stop linking them with cases of violence, theft or terrorism. Therefore, a “solidarity Europe” is necessary.

Italy: 5 Star Movement and Lega

The 5 Star Movement is disappointed with the current European Union project in its communication strategy on Twitter. The problem lies in the austerity policies raised by the European Parliament after the global economic crisis. As they say, these types of policies did not work. Contrarily, “they have destroyed the lives of Italian citizens.”

In this sense, the 5 Star Movement attributes all responsibility about what happens in Europe to the European Parliament since they are responsible for the mismanagement of issues such as the economic crisis, or the refugee crisis and therefore have generated a strong disaffection among citizens concerning the European political project.

Criticisms of the European Union by the 5 Star Movement revolve around two axes: the economy and immigration. Regarding the economy, in numerous messages they appeal to the need to implement an economic patriotism that prioritizes internal trade over foreign trade. On the one hand, they emphasize that, instead of helping them to overcome the economic crisis, austerity policies promoted by the European authorities have reduced Italy's ability to compete with the rest of the world's economies, something they consider essential if Europe wants Italy to be a member of the common project. Therefore, they raise the need to implement a minimum wage in Europe to keep all countries at the same level. The objective is to combat relocation and prevent Italian companies from moving to other countries simply because labor costs are lower in them.

On the other hand, the 5 Star Movement also espouses the need to promote employment policies. In this regard, they propose the so-called “Dignity Decree” as a model, approved by the Italian Parliament during August. With this project, the Italian government has decided on reducing the maximum duration of temporary contracts, offering a 50% discount on taxes paid by the employee during the next 3 years and has increased the compensation that the worker must receive in case of unfair dismissal. In this regard, they also propose that Europe increases funds for educational programs, research and business as a mechanism to stop the brain drain and to reward excellence.

Regarding immigration, the 5 Star Movement considers that given its location in the Mediterranean Sea, Italy receives a very high number of immigrants. They recognize that “the borders of Italy are the borders of Europe,” but they consider that the European Union does not consider all countries to be equal when it legislates on this issue. The 5 Star Movement argues that Italians feel aggrieved because in recent years they have assumed most of the migratory flow that reached the Mediterranean, so they feel “alone” facing a problem they consider global. In this regard, they believe that Europe must work together to allocate and divide the distribution of migrants equally among all countries.

Therefore, the 5 Star Movement reclaim the original project on which the European Union was founded on its creation. They “firmly believe” in a Europe based on the foundational principles that inspired it. That is to say: solidarity, dignity, democracy, freedom, and equality. For them, it is necessary to recover these values to move together toward the future and “the European elections held on May are a unique opportunity to start changing Europe.” For the 5 Star Movement the main goal is that “Italy plays an important role in European decision-making again.”

The Lega has developed an intense electoral campaign on social media platforms such as Twitter to manage the 2019 European elections. For Italians, the problems of the people are mainly summarized in two: the economy and immigration. Regarding the first, the party presents a very protectionist vision of the economy since they defend Italian products against those imported from Europe. In this way, they believe that winning in Europe would guarantee the protection of the Italian industry and commerce, which in several cases has been harmed by the lack of tariffs. Italians do not perceive Italy to be among the great countries of the European Union. This must be solved to become the country that was in past decades and, therefore, they want Italy to play a leading role within the European Union.

Immigration may be the issue that most worries the Lega. They talk about it in numerous messages, always using a negative tone and linking migrants to aspects such as insecurity or illegality. In addition, they consider that the distribution of immigrants among the countries of the European Union has not turned out to be as equitable as it should. Likewise, the 5 Star Movement, the Lega feels aggrieved by the distribution of immigrants among the countries that conform to the European Union, given that the bulk of immigration arrives in the Mediterranean and Italy is expected to welcome them and provide them asylum. However, the Lega manifest a much more restrictive and even xenophobic attitude that defends the prohibition of immigrants entering Italy. This aspect triggered numerous disagreements within the government coalition formed by the 5 Star Movement and the Lega, and ended in a rupture in August 2019. Therefore, they aspire to win in Europe to defend the Italian borders.

Mateo Salvini promotes the creation of a different Europe that “defends security, values traditional family and Christianity.” The leader of the Lega links immigration with illegality and insecurity and capitalizes on the increase of immigration to transfer citizens a sense of fear and insecurity connected to the fact that Italy cannot control its borders and, therefore, cannot dominate the migratory flow by being part of the European Union. He proposes that only immigrants who have permission can cross European borders. Therefore, Salvini defends the creation of a wall as a mechanism to stop immigration such as the one approved by the Hungarian government. In this regard, it is significant how the Lega made numerous allusions to the Hungarian government led by Viktor Orbán during the entire campaign. They consider this government an essential ally to build “a new Europe” in which the defense of national sovereignty and the struggle against immigration prevail. Thus, the Lega seeks the tightening of legislation to curb immigration, both legal and illegal, in Italy, encouraging a patriotism similar to the one defended by Marine Le Pen in France or Donald Trump in the United States.

The Lega argues that “Europe should not forget its origins.” However, they consider that the union is currently very far from what it was in the beginning since it is further from the people, and only protects the welfare of a few States. To move forward, Europe cannot forget its origins and the countries that conform it up cannot abandon their own culture, traditions and identity. In this context, the party led by Mateo Salvini is presented on Twitter as the only solution for Europe, the “uncomfortable option for the European Union,” and the only one able to solve the problems of the people. Their goal is to change Europe to “guarantee the future of our children,” a Europe “in which our children can dream.” To do this, Europe needs “a change,” a great reform that will take us to “a new Europe,” a “diverse Europe,” far from the bureaucrats and bankers who have moved the European Union away from the people. Again, as observed in Vox, the Lega activates the differentiation between the people and the elite of populist discourse. By facing the economic elites of the European Union, the Lega will guarantee the sovereignty of the Italian people.

France: Rassemblement National and France Insoumise

Rassemblement National has a very belligerent attitude toward the European Union on Twitter. The French populists believe that the European Union, a technocratic institution that works as a prison, does not represent the millenary Europe formed by the united peoples. The Brussels institutions, such as the European Commission, are made of officials. These organizations have the power and make the decisions, instead of the Parliament, chosen by the citizens of all European countries. In this regard, they argue that the Commission has no legitimacy to make decisions and, therefore, it is currently imposing guidelines that do not correspond to its authority. They consider this to be “totalitarian and undemocratic.”

Migration policies carried out by the European Union particularly concern Rassemblement National. They argue on Twitter that “borders are necessary for life because there is no living organism able to survive without finding food abroad and rejecting obstacles.” This statement means that immigration is an obstacle to the French interests and, therefore, must be rejected. Thus, they oppose the quotas of immigrants established by the European Union, since they consider that receiving more than 400,000 immigrants a year is too much. In addition, they claim that the Schengen treaty must be revoked, given that displaced workers steal employment from French workers, and protecting national workers must be a priority. They establish that before “accepting the miseries of the entire world,” the European Union should look for its people and put an end to these decisions that only bring “poverty, unemployment, and insecurity.” In this sense, they consider that returning borders to European countries is a measure of “common sense,” both in the economic field and on national security.

Besides, the party clearly and directly links immigration with terrorism. The criticism of the management of the migration crisis undertook by the European Union is reinforced with the praises made to “allies” such as Vladimir Putin's Russia or Mateo Salvini's Italy and their immigration management. Moreover, since they are currently “exposed to unprecedented migration flows,” they consider being exposed to terrorism. They even believe that along with those refugees fleeing the war in Syria, there are infiltrated terrorists from the Islamic State, who take advantage of the humanitarian aid to cross European borders and commit terrorist attacks, such as those suffered in April 2018.

Using this type of messages on Twitter, Rassemblement National seeks to generate fear and insecurity among citizens and present themselves as the only political option that will protect them from immigration and its consequences. For this party, immigrants are not included in the people. Immigrants are the others, a collective trying to take away the rights of citizens. Despite the disparity that characterizes immigration, they portray them as a homogeneous collective against which the people must fight to keep their rights. This way, they link immigration with the lack of job opportunities or with the reduction of social assistance, generating a negative representation of immigration in the collective imaginary of the French. Activating the friend/enemy axis (Schmitt, 2005) they seek to foster confrontation between the two groups, an aspect that can generate aggressions or vexations on the part of ultra-groups against people from other countries.

For this reason, Rassemblement National proposes to end the European Union as we know it today. Thus, in front of the European Union of technocrats, they propose a Europe formed by “free, sovereign and independent nations.” This way, each nation will be able to legislate to protect their people, instead of the current situation where a few decide what is best for everyone, an aspect that the French populists consider to be seriously damaging them on issues such as the economy or immigration. Rassemblement National strives to link the loss of sovereignty of the European Union with leaders such as Emmanuel Macron, president of the French republic, or Angela Merkel, the German chancellor. These leaders, according to the French populists, act against the people.

In the same line with the argument presented by Rassemblement National on Twitter, the France Insoumise consider that the European Union is not Europe since the European Union is currently a single market where citizens are subject to the dictatorship of banks and finances. Very critical of the austerity policies implemented during the last decade, they believe that France must withdraw from the European treaties that feed social and fiscal dumping, as they are annihilating public investments as well as frustrating the application of social policies. They place the accent on the lack of investment in healthcare or in fighting against gender violence.

In line with these are the criticisms to Emmanuel Macron since he is submitting to the mandate of the European Commission and, therefore, to the oligarchies and the liberal economic measures that use European treaties as mechanisms of execution to control the people. This way, they propose European elections as a plebiscite against Macron and the liberal policies of the European Union. Other things that they disapprove of the European Union and Macron are the inaction against climate change. Given the state of a climatic and ecological emergency, and the consequent loss of species, they claim that the European authorities are doing nothing. For this reason, they appeal for the environmentalist's vote in the European elections in the face of this climatic emergency. Besides, they defend the need to address the consequences of climate change and study how to prevent it. To suspend direct and indirect subsidies, to fossil energies, to bet on a 100% renewable energy future, to lead a common ecological agricultural policy for quality food, to build a Europe of zero waste where the circular economy is established are among their proposals.

Finally, given the refugee crisis that Europe has suffered in recent years, they defend the need to address the causes of immigration. They argue that “migrating is a pain, a necessity” as nobody leaves a country and a family for pleasure. Therefore, migrants should be treated with dignity. In this sense, borders should not serve to prevent people from fleeing war or a complicated situation in their countries of origin, but must be used primarily as a tool to impose taxes on tax traps and multinationals practicing tax evasion.

The France Insoumise present themselves as revolutionary on Twitter, as “the only ones capable of fighting against the extreme right and the extreme liberalism,” as “the only ones able to protect the people with solidarity and national sovereignty.” They define themselves as combat deputies, consistent and representative. Thus, each vote for the France Insoumise will serve to stand up to Brussels, to oppose Macron and its policies, and to strengthen its electoral program. In addition, they argue that they are not on their own, but have an alliance with parties such as Podemos in Spain, the Bloco in Portugal, or their Nordic allies, who will fight for the people. They want a “peace Europe” that brings social progress, democracy, emancipation, assuming responsibility to fight against climate change and ecological disaster. They define their project as humanist since they seek to live in peace and harmony with the rest of human beings, nature and animals, proposing a non-competitive Europe, based on cooperation, freedom, equality and fraternity among people, European nations and the rest of the world.

United Kingdom: The Brexit Party and UKIP

The Brexit Party was launched on the 20th of January 2019. The party led by Nigel Farage, ex-leader of the UKIP, seeks to attract those conservative and Labor voters supporting the British exit from the European Union. Due to its recent creation and its short history, The Brexit Party does not present a detailed electoral program and its communicative strategy on Twitter presents few messages focusing mainly on the issue of Brexit.

Europe's main problem is the loss of sovereignty resulting from becoming a member of the European project. Thus, they attribute all responsibility to the establishment, who legislate thinking about the benefit of a few States. In this context, they blame not only the bureaucrats of Brussels but also the two great parties governing the political life of the United Kingdom for centuries: Labor and Conservatives. They consider that “the bipartisan system is broken” because both parties broke their promises and will end up losing millions of followers if they negotiate with the European Union something other than Brexit.

The loss of sovereignty has generated the impossibility of legislating on fundamental issues such as the opening or closing of borders, or aspects related to employment, as well as the obligation to implement the treaties approved by the European Union, such as Schengen, which allows the free movement of people between the Member States. For The Brexit Party, Brexit is the only possible solution. The only way to recover the lost sovereignty and to be able to decide the future of the British is to leave the European Union. Therefore, they encourage supporters of Brexit, the so-called Brexiteers, to join the party and vote for them in the European elections. They define themselves as a movement for democracy, seeking to gather under their wing all those who consider themselves as “Democrats in favor of leaving the European Union and willing to change politics for the better.” Only this way can the United Kingdom “recover its reputation in the world.”

Moreover, we should point out that a large part of the messages published by The Brexit Party on Twitter regarding the electoral campaign refers to the electoral acts that occurred throughout the United Kingdom in May. These messages commonly contain images with party leaders surrounded by citizens. With this, they may want to demonstrate having a large number of followers despite its short history.

The communicative strategy of the UKIP on Twitter has followed the same line as the one executed by The Brexit Party. Their messages focus on highlighting the consequences of the loss of sovereignty for the United Kingdom. In this context, the UKIP blames the current situation of the British on both Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn, two politicians they harshly criticize. Also, they attack emblematic figures such as Tony Blair since he wanted to negotiate a second referendum. Since the mandate of the people has been to leave the European Union, they consider that negotiating the conditions for the United Kingdom to leave is a “humiliation” for the British political class. For the UKIP the result of the referendum was clear, so the British government must abide by the people's decision and leave the European Union without objecting or negotiating anything. They must simply leave as soon as possible. In addition, against those arguing that Brexit would harm business, the UKIP states that politicians like Corbyn or May are the ones damaging the economy with their efforts to remain in the European Union and to hold a second referendum. Not only that, but they consider that the position of both parties and their leaders are detrimental to the future of the nation.

“The great revolution in the history of mankind, past, present, and future, is the revolution of those determined to be free.” Using this quote pronounced by John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, they defend the idea that the establishment will not be able to stop the departure of the United Kingdom. The British people will manage to abandon the “corrupt” European Union using their mandate.

In line with the events linked to Brexit, the UKIP advocates that the only possible solution is leaving the European Union. It is too late for restoring the European Union as other countries claim. Therefore, one of the slogans of the campaign that they used as a hashtag on Twitter is #MakeBrexitHappen. The British people are urged to vote UKIP if they want Brexit to be real, whether or not there is a deal. Since its creation (27 years ago) the UKIP has been fighting to make Brexit happen. Also, they declare that the United Kingdom must regain sovereignty. They argue that they “have a plan,” which is to leave the European Union. They also claim “to have the necessary support from the people to execute it.” Furthermore, they emphasize that, if it wasn't for them, there would have never been a referendum.

Conclusions

The analysis carried out allows extracting the main discursive axes that the eight European populist parties analyzed present in their communicative strategy on Twitter regarding the European political project and Euroscepticism (Table 2). Thus, the activation of the four functions of the framing theory described by Entman (1993) can be identified: definition of the problem, attribution of responsibilities, moral assessment and approach to a solution.

The populist political parties analyzed believe that the main problem (the first function of framing by Entman) related to the European Union lies in the loss of sovereignty when belonging to this institution as member states must abide by certain policies they disagree with. These policies benefit some and harm others. Belonging to supranational organizations causes the loss of sovereignty since the State loses control to legislate, and therefore it is unable to rectify adverse economic or social situations. Vox, Lega, Rassemblement National, the UKIP and The Brexit Party defend in their Twitter profiles an idea of national sovereignty based on ethnic and isolationist values. These parties are actively fighting against the external enemy. On the contrary, France Insoumise defines sovereignty as a social and democratic issue that implies achieving equality for the people. This means that their interests prevail over those of the elite. In this sense, it is interesting to note how populist right-wing parties link immigration to the loss of sovereignty and to the national security problems that involve, with special attention to the inability to close borders as a result of the prohibition of European treaties (the third function of framing by Entman). In contrast, France Insoumise links the loss of sovereignty to a more social aspect such as climate change and the inefficiency of the European Union to address it, as well as the need to address the causes that have led so many people to emigrate and leave their home countries.

The exception to this point is Podemos and the 5 Star Movement. They consider austerity policies imposed on the Member States since the beginning of the global economic crisis in 2008 as the main problem of the European Union. From their view, these measures have proved highly ineffective since they have deteriorated the life of citizens. For Podemos, austerity policies have resulted in the discrediting of the European Union, which on the one hand implies an increase of the far-right parties demanding to leave the institution and, on the other, the EU seems to be at the service of the markets instead of serving the people. The 5 Star Movement believes that, in addition to aggravating the economic crisis, austerity has triggered a migration crisis that Europe has failed to manage, appealing to the need for an economic patriotism that prioritizes the welfare of the Italians. In short, we observe how, in general terms, the main problem for radical right populist parties is the loss of sovereignty, whereas for the left-populist parties is austerity policies.

In this context, the responsibility of the problems that the European Union has (the second function of framing by Entman) varies depending on the parties. Again, Podemos and the 5 Star Movement coincide in their analysis and point to the financial system and the elites of Brussels as the culprits of the bad situation experienced by the European political project. In a similar line are the criticisms of the Lega since they blame bankers and bureaucrats. As the party led by Matteo Salvini argues on Twitter, they are the actors who truly run the European Union and accuse them of legislating for the benefit of countries like Germany. Vox, Rassemblement National and France Insoumise are committed to blaming the oligarchies of Brussels and some leaders such as Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron. It is noteworthy that the French populist parties accuse the president of their country of not being belligerent enough to fight for the rights of the French in the European Union, and obeying the orders of leaders from other countries such as Merkel. Finally, the British populists agree in their diagnosis and attribute all responsibility to the European institutions and the leaders of the Conservative Party, Theresa May, and the Labor Party, Jeremy Corbyn, for not fulfilling the will of the British people to abandon the European Union. Thus, we observe two types of strategies regarding the attribution of responsibility. The first is to blame political and economic instances in an abstract way. The second, present in the communicative strategy of the French and British populists, is to criticize European politics in a national way, blaming the political leaders of their respective countries.

The moral valuation (the third function of framing by Entman) that populist parties develop also differs depending on their ideology. For radical right populist parties, the loss of sovereignty implies problems of national security, especially with regard to the opening and closing of borders. All of them stress the fact that they disagree with free movement of people and that they are willing to restrict the entry of immigrants into their respective countries, an aspect that the European Union membership does not allow state governments to do. The moral assessment made by the left-wing populist parties varies depending on their profiles. For Podemos, austerity policies have led to the emergence and consolidation of far-right political options aiming to end the existing European political project. In addition, they highlight the lack of actions regarding issues such as climate change, a highly problematic issue that requires urgent action. France Insoumise agrees on the latter assessment as they also emphasize that the European Union has avoided taking measures to tackle the migration crisis. Finally, the 5 Star Movement considers that austerity policies have generated both economic and migratory problems, an aspect that has caused the emergence of the so-called economic patriotism in countries such as Italy or France. These groups seek to improve the lives of national citizens as opposed to the lives of people from abroad.

Finally, the analysis has detected that the European populist parties propose three types of solutions (the fourth function of framing by Entman) to respond to the problems that the European political project is going through. First, the center and left-wing populist parties (Podemos, the 5 Star Movement, and France Insoumise) present ideas based on the need to recover the foundational principles that inspired the creation of the European Union, such as solidarity, cooperation or freedom. Secondly, the radical right populist parties such as Vox, Rassemblement National and the Lega believe that the only possible way is to execute a total re-foundation of the European Union, removing the power from Brussels to grant it to the States, to create a sort of Europe for the people. Thirdly and finally, the British populists present the strongest solution: leaving the European Union. For the UKIP and The Brexit Party the only possible option for the United Kingdom is to leave the institution since only then can they become a sovereign state, able to make its own decisions. Thus, we observe how ideology is a determining factor in the choice of the type of solution to apply. While the left-wing populist parties bet on a more constructive discourse aspiring to return to the beginning of the European political project, the radical right populist parties present a negative discourse based on the recovery of the sovereignty ceded by the member states, or on the exit of the European Union.

In this sense, Eurosceptic attitudes have been observed in the communicative strategies on Twitter of all the European populist parties analyzed, regardless of their trajectory and ideology.

Discussion

The results obtained in this research enable us to make two innovative contributions. On the one hand, the analysis conducted permit us to point out that the European populist parties studied, regardless of their ideology, run as Eurosceptic options, presenting a critical discourse on Twitter against the European political project. This aspect enables adding another dimension to the communicative style of populism (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007). On the other hand, this analysis also allows us to identify the dominant frames revolving around Euroscepticism: the loss of sovereignty and the austerity policies as the main problem of the European political project or the re-foundation, redefinition or abandonment of the European Union as a possible solution. In this case, ideology operates as a determining factor.

In response to RQ1, the presence of Euroscepticism has been detected in the messages of the Twitter accounts of the eight populist parties studied, regardless of their ideology. Although previous studies highlighted that Euroscepticism is normally representative of radical right populist parties (Wodak, 2015), this analysis has identified that it is also currently present in the communication strategies posed on Twitter by left-wing populist parties. Following the assumptions raised by Taggart and Szczerbiak (2002), we observed a “soft” form of Euroscepticism in the communication strategy of the left-wing populist parties on Twitter in which they disapprove some European Union policies. By contrast, right-wing populist parties are opposed to the process of European integration and want to re-found the European Union, an aspect that could be considered a “hard” form of Euroscepticism.

European populist actors, especially radical right populist parties, take advantage of citizens' frustration (Eurobarometer, 20181, 20192) to promote Eurosceptic discourse among users and to launch harsh criticism against the main leaders of the European Union as well as leaders from countries like Germany or France. The populist parties analyzed approve the founding principles of the European Union but are against those running the institution (Mudde, 2007). Thus, in addition to the appeal to the people and the criticism of the elites, Euroscepticism is also incorporated as an identity element of the rhetoric of European populist parties (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007).

Given the barriers imposed by conventional media, the analyzed populist political actors feed on the values inherent in the digital media system to favor their communication (Engesser et al., 2017b), thus taking advantage of the structure of online opportunity (Engesser et al., 2017a). Following a similar strategy to that employed by certain social movements, such as 15M (Casero-Ripollés and Feenstra, 2012) or the Platform of People Affected by Mortgage (Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés, 2016), populist political actors spread their messages on Twitter underlining the specific aspects that interest them the most, depending on their ideology.

In this sense, answering the RQ2, it has been identified that ideological differences do influence how messages dealing with the European Union are framed. Activating the four functions of the framing theory described by Entman (1993) in their discursive strategy on Twitter, populist parties have defined the problem, attributed the relevant responsibilities, made a moral assessment and, finally, raised a possible solution. The way of posing these functions is different in the communicative strategy on Twitter of the analyzed populist parties. They emphasize certain aspects or others depending on whether they are radical right or left-wing populist parties.

Globalization, embodied by supranational organizations such as the European Union, detracts sovereignty from the people (Mammone, 2009), while the State loses part of the control to legislate. At this point, in line with what was argued by authors such as Gerbaudo (2017), the question of sovereignty is the meeting point between left-wing and right-wing populism. The difference between the two lies in how they are proposing to reestablish the union (Gerbaudo, 2018). While the radical right populist parties bet on leaving the European Union or re-founding it to completely change it, the left-wing populist parties present a constructive discourse. In line with what was stated by other authors (Casero-Ripollés et al., 2017), these parties do not want to leave the European Union, but they do seek to improve their position within it. This creates a transnational nationalism shared by those states led by political options with the same ideology that support the same measures regarding issues such as the European Union's membership or immigration. This is corroborated by those messages in which they show their support to their allies, as occurs between Rassemblement National and the Liga or between France Insoumise and Podemos. Thus, uniting each other and sharing arguments, they take advantage of the political opportunity structure to gain strength before both citizens and European Parliament (Hall, 2000).

The results of this comparative study show that Euroscepticism is an attribute present in the communicative strategy on Twitter of European populist parties of both left and right. However, there are significant differences with respect to the frame of the messages related to the European Union, highlighting some aspects or others depending on ideology.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

LA-M collected data, conducted data analysis, developed the concept of the manuscript, and wrote the paper. AC-R wrote the paper and reviewed it. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the State Research Agency (AEI) of the Spanish Government under Grant CSO2017-88620-P.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Standard Eurobarometer 90 (November 2018), https://bit.ly/2T3YOyN

2. ^Standard Eurobarometer 91 (June 2019), https://bit.ly/39TwJQD

References

Aalberg, T., and de Vreese, C. H. (2017). “Introduction: comprehending populist political communication,” in Populist Political Communication in Europe, eds T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–25.

Abts, K., and Rummens, S. (2007). Populism versus democracy. Polit. Stud. 55, 405–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00657.x

Albertazzi, D., and McDonnell, D. (eds.). (2008). “Introduction: the sceptre and the spectre,” in Twenty-First Century Populism, (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 1–11.

Alonso-Muñoz, L. (2019). The “more is more” effect: a comparative analysis of the political agenda and the strategy on Twitter of the European populist parties. Eur. Polit. Soc. 20, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2019.1672921

Alonso-Muñoz, L., and Casero-Ripollés, A. (2016). La influencia del discurso sobre cambio social en la agenda de los medios. El caso de la Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca. OBETS. Rev. Ciencias Social. 11, 25–51. doi: 10.14198/OBETS2016.11.1.02

Alonso-Muñoz, L., and Casero-Ripollés, A. (2018). Communication of European populist leaders on Twitter: agenda setting and the “more is less” effect. El Prof. Información 27, 1193–1202. doi: 10.3145/epi.2018.nov.03

Atton, C. (2006). Far-right media on internet: culture, discourse and power. New Media Soc. 8, 573–587. doi: 10.1177/1461444806065653

Bartlett, J., Birdwell, J., and Littler, M. (2011). The New Face of Digital Populism. London: Demos.

Bennett, W. L., and Manheim, J. B. (2006). The one-step flow of communication. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 608, 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0002716206292266

Bergbauer, S., Jamet, J.-F., Schölermann, H., Stracca, L., and Stubenrauch, C. (2019). Global Lessons From Euroscepticism. VOX. CEPR Policy Portal. Available online at: https://voxeu.org/article/global-lessons-euroscepticism

Block, E., and Negrine, R. (2017). The populist communication style: toward a critical framework. Int. J. Commun. 11, 178–197.

Bos, L., van der Brug, W., and de Vreese, C. H. (2010). Media coverage of rightwing populist leaders. Communications 35, 141–163. doi: 10.1515/comm.2010.008

Bos, L., van der Brug, W., and de Vreese, C. H. (2011). How the media shape perceptions of right-wing populist leaders. Polit. Commun. 28, 182–206. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2011.564605

Burson-Marsteller (2018). Twiplomacy Study 2018. Twiplomacy. Available online at: https://twiplomacy.com/blog/twiplomacy-study-2018/

Butler, J. (2014). “‘Nosotros el pueblo.” Apuntes sobre la libertad de reunión,” in ¿Qué es un pueblo?, eds A. Badiou, J. Butler, G. Didi-Huberman, S. Khiari, and J. Rancière (Buenos Aires: Eterna Cadencia), 229–242.

Caiani, M., and Graziano, P. (2016). Varieties of populism: insights from the Italian case. Rivista Italiana Sci. Politica 46, 243–267. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2016.6

Canovan, M. (2002). “Taking politics to the people: populism as the ideology of democracy,” in Democracies and the Populist Challenge, eds Y. Mény and Y. Surel (New York, NY: Palgrave), 25–44.

Casero-Ripollés, A., and Feenstra, R. A. (2012). The 15-M movement and the new media: a case study of how new themes were introduced into Spanish political discourse. Media Int. Aust. 144, 68–76. doi: 10.1177/1329878X1214400111

Casero-Ripollés, A., Feenstra, R. A., and Tormey, S. (2016). Old and new media logics in an electoral campaign: the case of Podemos and the two-way street mediatization of politics. Int. J. Press Polit. 21, 378–397. doi: 10.1177/1940161216645340

Casero-Ripollés, A., Sintes-Olivella, M., and Franch, P. (2017). The populist political communication style in action: podemos's issues and functions on Twitter during the 2016 Spanish general election. Am. Behav. Sci. 61, 986–1001. doi: 10.1177/0002764217707624

Chiaramonte, A., Emanuele, V., Maggini, N., and Paparo, A. (2018). Populist success in a Hung parliament: the 2018 general election in Italy. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 23, 479–501. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2018.1506513

Colleoni, E., Rozza, A., and Arvidsson, A. (2014). Echo chamber or public sphere? Predicting political orientation and measuring political homophily in Twitter using big data. J. Commun. 64, 317–332. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12084

de Vreese, C. H., Esser, F., Aalberg, T., Reinemann, C., and Stanyer, J. (2018). Populism as an expression of political communication content and style: a new perspective. Int. J. Press Polit. 23, 423–438. doi: 10.1177/1940161218790035

Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F., and Büchel, F. (2017a). Populism and social media. How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 1109–1126. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

Engesser, S., Fawzi, N., and Larsson, A. O. (2017b). Populist online communication: introduction to the special issue. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 1272–1292. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328525

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Esser, F., Stepinska, A., and Hopmann, D. (2017). “Populism and the media: cross-national findings and perspectives,” in Populist Political Communication in Europe, eds T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese (New York, NY: Routledge), 365–380.

Flesher Fominaya, C. (2015). Redefining the crisis/redefining democracy: mobilising for the right to housing in Spain's PAH Movement. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 20, 465–485. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2015.1058216

Fuchs, C. (2017). Donald Trump: a critical theory-perspective on authoritarian capitalism. tripleC Commun. Cap. Crit. 15, 1–72. doi: 10.31269/triplec.v15i1.835

Gainous, J., and Wagner, K. M. (2014). Tweeting to power. The Social Media Revolution in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gamson, W. A. (2004). On a sociology of the media. Polit. Commun. 21, 305–307. doi: 10.1080/10584600490481334

Gerbaudo, P. (2014). “Populism 2.0,” in Social Media, Politics and The State: Protests, Revolutions, Riots, Crime and Policing in the Age of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, eds D. Trottier and C. Fuchs (New York, NY: Routledge), 16–67.

Gerbaudo, P. (2018). Social media and populism: an elective affinity? Media Cult. Soc. 40, 745–753. doi: 10.1177/0163443718772192

Graham, T., Broersma, M., and Hazelhoff, K. (2013). “Closing the gap: Twitter as an instrument for connected representation,” in The Media, Political Participation and Empowerment, eds R. Scullion, R. Gerodimos, D. Jackson, and D. Lilleker (London: Routledge), 71–88.

Groshek, J., and Engelbert, J. (2013). Double differentiation in a cross-national comparision of populist political movements and online media uses in the United States and the Netherlands. New Media Soc. 15, 183–202. doi: 10.1177/1461444812450685

Guerrero-Solé, F. (2018). Interactive behavior in political discussions on Twitter: politicians, media, and citizens' patterns of interaction in the 2015 and 2016 electoral campaigns in Spain. Soc. Media Soc. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1177/2056305118808776

Hall, J. A. (2000). Estado y Nación: Ernest Gellner y la Teoría del Nacionalismo. Madrid: Cambridge University Press.

Hameleers, M. (2018). A typology of populism: toward a revised theoretical framework on the sender side and receiver side of communication. Int. J. Commun. 12, 2171–2190.

Hawkins, K. A. (2010). Venezuela's Chavismo and Populism in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511730245

Ivaldi, G. (2018). Contesting the EU in times of crisis: The Front National and politics of Euroscepticism in France. Politics 38, 278–294. doi: 10.1177/0263395718766787

Jackson, N. A., and Lilleker, D. (2011). Microblogging, constituency service and impression management: UK MPs and the use of Twitter. J. Legis. Stud. 17, 86–105. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2011.545181

Jagers, J., and Walgrave, S. (2007). Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties' discourse in Belgium. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 46, 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Jamieson, K. H., and Cappella, J. N. (2008). Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Koopmans, R., and Olzak, S. (2004). Discursive opportunities and the evolution of right-wing violence in Germany. Am. J. Sociol. 110, 198–230. doi: 10.1086/386271

Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: a conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Commun. Theory 24, 42–60. doi: 10.1111/comt.12029

Kriesi, H. (1995). “The political opportunity structure of new social movements: Its impact on their mobilization,” in The Politics of Social Protest: Comparative Perspectives on States and Social Movements, ed J. C. Jenkins (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

Kriesi, H. (2007). The role of European integration in national election campaigns. Eur. Union Polit. 8, 83–108. doi: 10.1177/1465116507073288

Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West Eur. Polit. 37, 361–378. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

Mammone, A. (2009). The eternal return? Faux populism and contemporarization of neo-fascism across Britain, France and Italy. J. Conemp. Eur. Stud. 17, 171–192. doi: 10.1080/14782800903108635

Mazzoleni, G. (2003). “The media and the growth of neo-populism in contemporary democracies,” in The Media and Neo-Populism, eds G. Mazzoleni, J. Stewart, and B. Horsfield (London: Praeger), 1–23.

Mazzoleni, G. (2008). “Populism and the media,” in Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, eds D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 49–64.

McLaren, L. M. (2006). Identity, Interests and Attitudes to European Integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford: Stanford Univeristy. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvqsdsd8

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 39, 541–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511492037

Pencheva, D., and Maronitis, K. (2018). Fetishizing sovereignty in the remain and leave campaigns. Eur. Polit. Soc. 19, 526–539. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2018.1468948

Rooduijn, M. (2014). The nucleus of populism: in search of the lowest common denominator. Gov. Oppos. 49, 537–599. doi: 10.1017/gov.2013.30

Rooduijn, M., and Akkerman, T. (2017). Flank attacks: populism and left right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Polit. 23, 193–204. doi: 10.1177/1354068815596514

Rovira Kaltwasser, C., and Taggart, P. (2016). Dealing with populists in government: a framework for analysis. Democratization 23, 201–220. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2015.1058785

Taggart, P., and Szczerbiak, A. (2002). “The party politics of euroscepticism in EU member and candidate states,” in Opposing Europe Research Network Working Paper (Turin), 6, 1–45.

Tarrow, S. (1994). Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action and Mass Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Usherwood, S. (2019). Shooting the fox? UKIP's populism in the post-Brexit era. West Eur. Polit. 42, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1596692

Vaccari, C., and Valeriani, A. (2015). Follow the leader! Direct and indirect flows of political communication during the 2013 Italian general election campaign. New Media Soc. 17, 1025–1042. doi: 10.1177/1461444813511038

van Dijk, T. A. (2006). Ideology and discourse analysis. J. Polit. Ideol. 11, 115–140. doi: 10.1080/13569310600687908

van Elsas, E. J., Hakhverdian, A., and van der Brug, W. (2016). United against a common foe? The nature and origins of Euroscepticism among left-wing and right-wing citizens. West Eur. Polit. 39, 1181–1204. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1175244

van Klingeren, M., Boomgaarden, H. G., and de Vreese, C. H. (2013). Going soft or staying soft: have identity factors become more important than economic rationale when explaining euroscepticism? J. Eur. Integr. 35, 689–704. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2012.719506

Vasilopoulou, S. (2018). “The radical right and Euroskepticism,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, ed J. Rydgren (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 122–140.

Verweij, P. (2012). Twitter links between politicians and journalists. J. Pract. 6, 680–691. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2012.667272

Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: populism in the study of Latin American Politics. Comp. Polit. 34, 1–22. doi: 10.2307/422412

Keywords: populism, political communication, Euroscepticism, Twitter, Europe

Citation: Alonso-Muñoz L and Casero-Ripollés A (2020) Populism Against Europe in Social Media: The Eurosceptic Discourse on Twitter in Spain, Italy, France, and United Kingdom During the Campaign of the 2019 European Parliament Election. Front. Commun. 5:54. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00054

Received: 23 February 2020; Accepted: 29 June 2020;

Published: 07 August 2020.

Edited by:

Rasha El-Ibiary, Future University in Egypt, EgyptReviewed by:

Andrijana Rabrenovic, Independent Researcher, Bijelo Polje, MontenegroKostas Maronitis, Leeds Trinity University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Alonso-Muñoz, lalonso@uji.es

Laura Alonso-Muñoz

Laura Alonso-Muñoz Andreu Casero-Ripollés

Andreu Casero-Ripollés