Increasing Readiness to Grow Traffic Safety Culture and Adopt the Safe System Approach: A Story of the Washington Traffic Safety Commission

- 1Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, United States

- 2Washington Traffic Safety Commission, Olympia, WA, United States

Growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach are strategies to support achieving a vision of zero traffic fatalities and serious injuries. However, adopting these strategies requires organizational change. Change is more likely to occur and be sustained by growing organizational readiness for change. Change readiness is driven by perceptions that 1) the change aligns with the organization’s culture 2) the organization (e.g., leadership, staff), is committed to the change, and 3) the organization has the resources necessary to make the change. The Washington Traffic Safety Commission has been engaged in a change process that focuses on growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach for many years. This article shares insights from their journey that other organizations can use to bolster their own change efforts.

Introduction

Many jurisdictions have adopted a vision of zero traffic fatalities and serious injuries (Vision Zero). However, year-to-year reductions in traffic fatalities and serious injuries have declined since 2012, and recently traffic fatalities and serious injuries have increased (Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), 2022). This has resulted in a call to “prioritize safety by adopting a Safe System approach and creating a positive safety culture” (National Safety Council, 2022).

Growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach are related (Ward et al., 2019a). Traffic safety culture has been defined as “the shared belief system of a group of people, which influences road user behaviors and stakeholder actions that impact traffic safety” (Ward et al., 2019b, p. 8). The United States Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) describes the Safe System approach using six principles (deaths and serious injuries are unacceptable, humans make mistakes, humans are vulnerable, responsibility is shared, safety is proactive, and redundancy is crucial), which are applied to five elements (safe road users, safe vehicles, safe speeds, safe roads, and post-crash care). “The Safe System approach requires a supporting safety culture that places safety first and foremost in road system investment decisions” (Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), 2022).

Growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach represent meaningful changes for any organization. Changing what we do (behavior/action), how we do it (process), and—more fundamentally—why we do it (culture) characterize “transformational change.” Transformational change is much more likely when an organization is ready to change (change readiness) and more likely sustained when using a managed process (Combe, 2014).

This article shares anecdotes from the Washington Traffic Safety Commission (WTSC) and its experiences with growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach drawn from an interview with two WTSC leaders, Director Shelly Baldwin and Program Director Wade Alonzo, conducted in November 2021. Storytelling is a way we can share our experiences and culture. Traffic safety organizations can learn from the WTSC’s experiences in increasing change readiness and therefore be more successful in their own change efforts.

Model of Change Readiness

Changing an organization is a complex undertaking. Change requires new effort to instigate and support that change. Our capacity to make this effort is determined by our “readiness for change.” According to Weiner (2009), readiness for change “refers to organizational members’ shared resolve to implement a change and shared belief in their collective capability to do so” (p. 1).

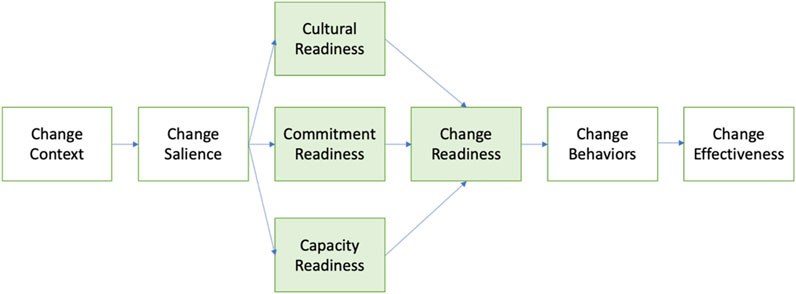

As shown in Figure 1, this change readiness process begins with contextual factors that make the change necessary. Examples of contextual factors include the recognition that the current increases in traffic fatalities are a “crisis” as well as the increasing expectations for equity in traffic safety. The perceived importance of this change (salience) is determined by the perceived alignment of the change with the accepted mission/purpose of the organization.

FIGURE 1. A process for change readiness (adapted from Combe, 2014).

Given a context motivating change and a perception that this change is salient to an organization, change readiness is driven by perceptions that 1) the change aligns with the organization’s culture (cultural readiness) 2) the organization (e.g., leadership, staff), is committed to the change (commitment readiness), and 3) the organization has the resources necessary to make the change (capacity readiness) (Combe, 2014).

Change readiness then drives change behaviors, both behaviors that exemplify the change and behaviors outside of formal roles that support the change process (e.g., being a champion for the change process). Examples of supportive behaviors that can initiate and sustain the process of change include championing change initiatives, working together, persevering, and adopting new processes. In the final phase, the organization integrates and sustains the change by encoding these operations into its policies and procedures.

An Example: The Washington Traffic Safety Commission

This section provides examples of actions taken to grow change salience, cultural readiness, commitment readiness, and capacity readiness by one organization: the Washington Traffic Safety Commission (WTSC).

The WTSC is established by state statute and includes ten commissioners representing various state agencies and organizations. The WTSC has 26 employees including program managers who oversee the distribution of state and federal funds to achieve their vision.

Change Context

From 2012 to 2021, 4,906 people died, and 19,276 people were seriously injured in vehicle-related crashes in Washington with a notable 12% increase in fatalities in 2021 (compared to the previous five-year average). These levels of fatalities and serious injuries created a context for change. “We have recognized for many years that we are not seeing the decreases needed to get to zero. Certainly, 2021 was an example of going in the wrong direction,” said Director Shelly Baldwin.

Change Salience

The mission of the WTSC is to lead statewide efforts and build partnerships to save lives and prevent injuries on Washington’s roadways for the health, safety, and benefit of communities. Its vision is zero deaths and serious injuries because every life counts. This mission and vision created a high level of salience for the organization to change and focus on growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach.

The structure of the WTSC (i.e., a commission of leaders from across state government) inherently supported this change. Baldwin: “The Traffic Safety Commission has always been lucky when I look at other highway safety offices, specifically, in that by law, we’re an independent small agency run by a commission, and all the other state agencies that have an influence on traffic safety are members of our commission. Partnership comes super natural and easy to us. We understand that an agency of 25 people is not going to be able to overcome the nearly 600 traffic fatalities that are occurring on our roadways by ourselves. It is always going to be about partnership.”

Cultural Readiness

Cultural readiness refers to the alignment of the organization’s shared beliefs, values, and practices with the proposed change efforts (Combe, 2014). Many of the WTSC’s values align with growing traffic safety culture and adopting a Safe System approach including servant leadership (“We are public servants whose calling is leadership in traffic safety”), collaboration (“We build community by listening, inspiring dialogue, and utilizing the talents of all”), innovation (“We continuously challenge processes and search for better ways to accomplish our work”), and learning (“We seek first to understand in order to gain new insights and expanded perspectives”).

“This is one of the few agencies where I think you can ask anybody and they could tell you what our values are. We take innovation and learning seriously, and I think that was part of making the ground fertile for these seeds to grow,” stated Program Director Wade Alonzo.

In 2018, the WTSC explored alignment among commissioners, staff, and stakeholders. Baldwin: “Before you start thinking about strategies to change the culture amongst road users, traffic safety stakeholders should also reflect on their own.” The WTSC worked with the Center for Health and Safety Culture (CHSC) at Montana State University to assess the degree of alignment among commissioners, staff, and stakeholders around the organization’s values. This assessment revealed the need to strengthen alignment around the organization’s values.

To foster that alignment, staff have been actively reflecting on the WTSC’s values during regular staff meetings (an exercise called “A Values Minute”) to connect their work and change efforts with their organizational values. Baldwin: “These values helped us to make changes because they were already a part of our organizational culture.”

Baldwin began to ask important questions: “We receive specific streams of funding, and there is often not a good linear relationship between that investment and a reduction in deaths. A classic question we learned to ask is ‘Are we busy or are we effective?’ And that kind of evaluative thinking can really change how you think about what you want to be doing.”

Alonzo added, “Staff now regularly ask ‘Are we being busy or effective?’”

An example of this change in thinking is exemplified in a story about communication shared by Baldwin:

When we were testing our “Together We Get There” campaign, we asked our focus groups to think about traditional traffic safety messages that they could remember. We gave them a feeling wheel full of different emotions, and we asked them to think of that commercial and then tell us how that PSA made them feel.

We didn’t know what ads or messages they were thinking of necessarily, so they were kind of all over the map but mostly grounded in fear and anger—emotions which we know are not the best places to be to ask somebody to learn something. They’re going to reject it or they’re going to fight it or they’re going to just ignore it.

When we showed them our concept and asked them how they felt, the emotion wheel flipped on the other side. It was joy; it was surprise. So, I have a very good grasp of the difference—about the place that we put people when we talk to them this way, as opposed to talking to them about the horrible outcomes. We know it happens -- people die, and it's horrible, and we keep that in our hearts all the time. It is not that we ignore that. But, we’re asking for a partnership with people that’s different than shaking our finger at them and telling them all the things we don’t want them to do. We’re helping them see the things we want them to do. And that’s a whole different communication space.

Traffic safety organizations working to grow traffic safety culture and adopt a Safe System approach can consider how their organizational values and practices can support their change efforts and consider values and practices that may be misaligned. They can also ask difficult questions without immediate answers to create the space for new ways of working to emerge.

Commitment Readiness

Commitment readiness includes an organization’s “shared resolve to implement a change” (Weiner, 2009, p.1). The commitment of an organization’s staff to see the change effort through is an indicator of commitment readiness (Combe, 2014). Elements of organizational commitment that are particularly salient to readiness include time commitment, involvement, skill, and perceived value (Combe, 2014).

The WTSC has recognized that growing traffic safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach are long-term strategies. The Commission adopted the goal of zero deaths and serious injuries in 2000 and established 2030 as the deadline—a year that seemed a long time in the future at the time. Since then, the leadership has been committed to the vision and has been willing to challenge itself and ask difficult questions. “It is easy to do what we’ve always done...but we have to pursue zero -- we have to be intentional. We can’t sit back and think others are going to solve our problems,” said Baldwin. “Within the United States, it seems to me that everybody should be asking the question about what’s next? What do we need to try and embrace next time? Because we need to make change … I am a big believer in the fact that we find what we’re looking for. So, if you’ve got that nagging feeling that it's not quite right, I think it behooves you to go ahead and pay attention to that feeling.”

Baldwin began training and working on traffic safety culture in 2016. The WTSC engaged the CHSC in a project to explore traffic safety culture around driving under the influence of cannabis and alcohol (DUICA) in 2017 as a way for staff to develop their understanding of traffic safety culture. The WTSC has continued to prioritize providing training and ongoing technical assistance to staff members ever since. Baldwin: “We have to make space for conversations, and not just with audiences across Washington, but with our own staff. The more conversations we have around this concept and how we’re implementing it, the more focused and thoughtful we become in our approach.”

Organizations can focus on developing shared understanding about concepts such as traffic safety culture, proactive traffic safety, Vision Zero, and a Safe System approach. Common understanding among employees and stakeholders motivates commitment and increases engagement in the change process.

Capacity Readiness

Capacity readiness includes an organization’s ability to mobilize and apply supportive work processes, organizational systems, and resources including physical, technological, and human such as knowledge and skills to support and sustain change efforts (Combe, 2014).

The WTSC is leveraging its existing capacities and growing new ones. Baldwin: “I think one of our superpowers is convening—it’s always been there. That has led us to embrace a positive culture framework.”

The WTSC realized there was a need to change some of their existing work processes. Alonzo noticed when he came to the WTSC that “due to the way we’re funded, it creates a very cyclical nature to our work, and I was really interested to see that we really focused on about 1 year at a time—a 1 year hamster wheel I call it.” However, he felt they needed multi-year cycles to support the longer-term culture-based strategies they were starting to invest in.

They even examined their language. Alonzo: “We really had to step back and agree on language. One of the first things we did was to create a glossary of words. In some places, we had to reconcile four different definitions, but this was really a key piece. We have also created a process improvement committee to recognize what we need to change in our processes and embed those in our digital grant management system.”

The WTSC also began challenging their approaches to funding and wanting more around evaluation. Alonzo: “I was new, and I did interviews with my program managers. I heard them questioning how we were investing our funds. We did a small study and found that about 70% of the projects we funded were the same every year. We wondered about innovation. I was also hearing that program managers were really hungry for ways to evaluate the effectiveness of their work other than watching crash numbers. We felt for a long time that crashes, which are affected by so many factors outside of our influence, are a poor barometer of our success.” They realized that they could measure culture (shared attitudes and beliefs) and use a process like the CHSC’s Positive Culture Framework to facilitate evaluating, learning, and improving their efforts.

Some organizations may feel they don’t have the time or funding to grow capacity. However, Baldwin has not found this to be a barrier: “As far as money goes, this has not been expensive. It is been about training; it's been about time spent in conversation. It is been very, very manageable, and we’ve set aside money to explore this every year, a little bit. Every year we get a little more training, and we have a few more conversations. And we have more time to think about how we can make these changes. So, money wise, I think any highway safety office could probably find the resources to do this. Timewise, we had to make a conscious decision to change our process enough to give us time to make this change, and that was the commitment.”

Conclusion

Organizational readiness for change is influenced by shared commitment and confidence to implement an organizational change (Weiner, 2009). Intentionally growing organizational readiness is likely to lead to greater success in organizational change efforts that require collective behavior change. Recognizing there is no “one best way” to increase organizational readiness for change (Weiner, 2009) and learning from the experiences of others can provide insights to support one’s own organizational change efforts to reach our collective goal of Vision Zero.

Baldwin sums it up in a story:

We’ve embraced the positive culture approach, and one of the best things about that has been recognizing, that prior to this, we thought of our customer as an unwilling customer—like a young man who embraces risky driving behaviors and isn't going to listen to us, no matter what we say, and doesn’t appreciate the things that we try to do to keep the road safe. Now, we see our customer as the majority of the population in Washington. We see how few people actually drive after drinking and how many people actually intervene to prevent a drunk driving trip. I think those pieces of information have been world view altering for us, so that we’re now talking more to the people who are more likely to hear what we have to say and are more likely to take that proactive step.

One example from this weekend is from some A/B testing on Facebook for our upcoming prevention campaigns. This ad was about a woman who had her arms up and behind her was kind of like the superhero arms coming up around her, and the message was about how most people in Washington say something or do something to intervene if someone’s going to drive impaired. And the ad asked: What are your stories?

We’ve run lots and lots of Facebook ads, and prior to this, our ads were focused largely on enforcement, upcoming enforcement campaigns, and the fact that extra police would be out. The comments were what you expect—not super positive or thoughtful comments.

This weekend, I kept seeing these hits from our Facebook ad with really deep, thoughtful, questions and stories. People were talking about things like “When my mom was drinking, we tried to make her stop and we couldn’t, so we finally would remove the battery from her car, and she was so mad at us, but she’s still here.” The stories and questions kept coming; there was legitimate conversation. This approach is just giving us this engagement at a deeper level with people who do care about the safety of our roads and helping them to see their role—what they can do.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Combe, M. (2014). Change Readiness: Focusing Change Management Where it Counts. PMI White Paper. Available at: https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/change-readiness-11126#:∼:text=Change%20readiness%20takes%20a%20critical,of%20the%20program%2Fproject%20outcomes (Accessed May 9, 2022).

Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) (2022). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Available at: https://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/Main/index.aspx (Accessed June 8, 2022).

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) (2022). Zero Deaths – Saving Lives through a Safety Culture and a Safe System. Available at: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/zerodeaths/zero_deaths_vision.cfm (Accessed May 9, 2022).

National Safety Council (2022). Road to Zero: A Plan to Eliminate Roadway Deaths. Available at: https://www.nsc.org/road-safety/get-involved/road-to-zero (Accessed May 9, 2022).

Ward, N., Otto, J., and Finley, K. (2019b). Traffic Safety Culture Primer. Bozeman, MT: Center for Health and Safety Culture, Montana State University. Available at: https://www.mdt.mt.gov/other/webdata/external/research/docs/research_proj/tsc/TSC_PRIMER/PRIMER.pdf.

Ward, N., Otto, J., and Jennings, B. (2019a). How Are Vision Zero, Safe System, and Traffic Safety Culture Related? Saf. Compass Winter 2019 13 (1), 9–10.

Keywords: traffic safety, vision zero, safe system approach, safety culture, change readiness (CR)

Citation: Otto J, Ward N, Finley K, Baldwin ST and Alonzo W (2022) Increasing Readiness to Grow Traffic Safety Culture and Adopt the Safe System Approach: A Story of the Washington Traffic Safety Commission. Front. Future Transp. 3:964630. doi: 10.3389/ffutr.2022.964630

Received: 08 June 2022; Accepted: 23 June 2022;

Published: 12 July 2022.

Edited by:

Huaguo Hugo Zhou, Auburn University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lingtao Wu, Texas A&M University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Otto, Ward, Finley, Baldwin and Alonzo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nic Ward, nward@montana.edu

Jay Otto

Jay Otto Nic Ward

Nic Ward Kari Finley

Kari Finley Shelly T. Baldwin

Shelly T. Baldwin Wade Alonzo

Wade Alonzo