- 1Department of Health Management, School of Health Management, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China

- 2Department of General Practice, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China

- 3Beijing Children's Hospital, Capital Medical University, National Center for Children's Health, Beijing, China

Objective: Hospital violence remains a global public health problem. This study aims to analyze serious hospital violence causes in China and the characteristics of perpetrators. It likewise seeks to understand frontline personnel's needs and put forward targeted suggestions.

Methods: Serious hospital violence cases from 2011 to 2020 in the China Judgment Online System (CJOS) were selected for descriptive statistical analysis. A total of 72 doctors, nurses, hospital managers, and security personnel from 20 secondary and tertiary hospitals in China were selected for semi-structured interviews.

Results: Of the incidents, 62.17% were caused by patients' deaths and dissatisfaction with their treatment results. Moreover, it was found that out-of-hospital disputes (11.14%) were also one of the main reasons for serious hospital violence. The perpetrators were mainly males (80.3%), and had attained junior high school education or lower (86.5%). Furthermore, most of them were family members of the patients (76.1%). Healthcare workers urgently hope that relevant parties will take new measures in terms of legislation, security, and dispute handling capacity.

Conclusion: In the past 10 years, serious hospital violence's frequency in China has remained high. Furthermore, their harmful consequences are more serious. The causes of hospital violence are diverse, and the characteristics of perpetrators are obvious. Frontline healthcare workers urgently need relevant parties to take effective measures in terms of legislation, security, and dispute handling capacity, to prevent the occurrence of violence and protect medical personnel's safety.

Introduction

Hospital violence can be defined as an incident in which healthcare workers or providers are abused, threatened, or attacked in connection with their work (1). It involves an explicit or implicit threat healthcare workers' safety, well-being, or health (1). Hospital violence exists in many countries in the world. As such, it is still a global public health problem (2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 8–38% of healthcare workers suffered from physical violence at work in 2019 (3). This figure is even higher in Asia (4). This is why workplace violence in China's hospitals has been the focus of many previous studies. Since 2020, the killing of doctors in the emergency department of Beijing Civil Aviation General Hospital (5, 6) and the explosion of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (7) have pushed the vicious violence problem to the forefront of public opinion in China.

There have been many previous studies on hospital violence. A nationwide survey of healthcare workers in China showed that hospital violence incidence was at 65.8%. Verbal violence accounted for 64.9% of the total hospital violence cases, while physical violence and sexual harassment accounted for 11.8 and 3.9%, respectively (8). Workplace violence incidence among healthcare workers in children's hospitals in China is more serious than that in general hospitals. A total of 68.6% of healthcare workers in children's hospitals in China have experienced at least one hospital violence incident (9). Patient factors such as emotional control ability, mental state, education level, and gender may be risk factors for hospital violence. Similarly, medical factors such as work experience, service system efficiency, and healthcare workers' poor communication abilities may be risk factors as well (10–12). Hospital violence's continuous occurrence has had a serious negative impact on healthcare workers' physical and mental health. This resulted in some healthcare workers having negative emotions such as anxiety (13–15), depression (16, 17), job burnout (18), and job dissatisfaction (18). Furthermore, it even directly or indirectly caused medical personnel to have suicidal tendencies. Hospital violence also seriously affects the doctor–patient relationship and makes doctors practice defensive medical behavior. This reduces the quality of health services and makes the trust between doctors and patients extremely fragile. Therefore, the contradiction between doctors and patients is further deepened (19–22). In the long run, hospital violence is bound to have a far-reaching negative impact on China's medical and health system.

In the past few years, the Chinese government has recognized hospital violence's negative impact on China's doctor–patient relationship and the development of China's health cause. Relevant laws were promulgated and a series of measures were taken, but hospital violence still occurs frequently. Thus, it still poses a serious threat to healthcare workers' physical and mental health and their order of diagnosis and treatment in the hospital. This phenomenon further increases the estrangement between doctors and patients, worsening the already fragile doctor–patient relationship (23). It has become the common expectation of all sectors of society to take more targeted measures in effectively preventing and controlling hospital violence.

There have been relatively few previous studies on actual cases of serious hospital violence. The data from these studies came from network reports. Thus, the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the information were poor, making it difficult to reflect the real situation of serious hospital violence in China. The present study will use Chinese court judgments as research data. It will extract real and accurate information related to hospital violence systematically, and comprehensively analyze the factors inducing hospital violence, and explore perpetrators' characteristics. This will provide a basis for relevant parties to aid in preventing and controlling the occurrence of hospital violence. At the same time, based on the analysis of inducing factors and relevant characteristics, this study will select medical personnel and managers of hospitals at all levels for in-depth interviews. This will help us understand frontline personnel's urgent needs regarding the prevention and control of hospital violence. This, in turn, will lead to more targeted and effective prevention and control measures.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection

This study's qualitative data comes from the judgment documents published in the China Judgment Online System (CJOS), which is operated and maintained by the Supreme People's Court of China. The case judgments of all courts in China's 31 provinces can be retrieved from this website (except for special cases involving national security, juvenile delinquency, and criminal crimes, or cases people's courts should not publish on the Internet). We used January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2020 as the search dates to study the occurrence of serious hospital violence in China. We used keywords such as “hospital,” “violence,” “hospital violence,” “medical dispute,” “hospital order,” “violent injury doctor,” “doctor,” “nurse,” and “healthcare workers” for single keyword retrieval or combined keyword retrieval. We were able to retrieve 63,262 judgments from our searches. Four graduate students carefully read and screened these judgments, and we excluded repeated cases and those that had nothing to do with hospital violence. For judgments with missing relevant information, we searched the relevant information of the events on Baidu news, Weibo, Netease News, Tencent News, Sina News, and other Internet platforms according to the events' time, place, and other information. The events' missing information were supplemented through a mutual confirmation of news information from multiple websites. After excluding irrelevant judgments, we were left with 341 judgments which involved a total of 873 violent criminals.

Based on the above data, we conducted expert consultation and subject group discussion, and determined the outline of a semi-structured interview. The outline consisted of two parts: basic information and open-ended questions. Basic information included five questions regarding gender, age, education, occupation, and hospital level of the interviewees. There were two open-ended questions (Appendix 1). Using this interview outline, we conducted semi-structured interviews with convenient sampling of 72 doctors, nurses, hospital managers, and security personnel from 20 secondary and tertiary hospitals in China from March 2021 to June 2021. This study sample was chosen as they have a deeper understanding of hospital violence and more experience in preventing such incidents. To avoid bias in the interview results due to different levels of hospitals, our survey included secondary and tertiary hospitals. To a certain extent, Beijing and Heilongjiang Province can represent the current situation of China's economically developed and underdeveloped provinces, respectively. Therefore, we selected medical personnel in medical institutions in these two provinces to ensure that interviews reflect frontline medical personnel's actual need to prevent and control hospital violence. Furthermore, interviews help put forward targeted and effective countermeasures to prevent and control hospital violence.

The researchers explained the study's purpose to the respondents and obtained their informed consent before the interview. The researchers conducted face-to-face interviews in an independent place, with Chinese as the interview language. The entire interview process was recorded. The interview began with an open-ended question: “Can you describe a violent incident in the hospital workplace that impacted you most.” The follow-up question was “Based on your personal experience, what measures must be taken to effectively prevent and control such incidents?” Each interview lasted 32–71 min and was conducted during the respondents' free time. A HKUST iFLYTEK Voice Recorder was used to record each interview. HKUST iFLYTEK voice recorder is an intelligent recording device, which can automatically identify the use scene, reduce noise, and safely store the recorded content in the cloud. The respondents' real names were replaced by pseudonyms to ensure their anonymity. After the interview, the recordings were transcribed verbatim.

Variable Coding and Data Analysis

After the screening of judgments, five researchers carefully read 50 judgments and selected relevant characteristic variables of hospital violence. They then conducted group discussions according to their selection results to determine the variables' standard names, types, and specific codes. A total of 18 characteristic variables related to violence were identified. The research team divided these variables into two categories: serious hospital violence incidents and perpetrators. Nine basic information variables (hospital level, department, cause, means of implementation, category of victim, and consequences of violence) were identified regarding serious hospital violence incidents. Similarly, nine characteristic variables (gender, age, education, occupation, criminal record, history of violent crime, mental state, and relationship with patients) were identified for the perpetrators. The five researchers then read 341 judgments in detail according to the selected variables and picked the variable information. The researchers conducted descriptive statistical analysis on the characteristics of hospital violence. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 and Microsoft Excel 2019.

Content analysis is a research method that subjectively explains text data's content through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying topics or patterns. It is used to analyze open problem data (24). In this study, two social medicine doctoral students with qualitative research experience independently coded the data using hybrid inductive and deductive coding methods (24). The inconsistency between the students' codes was solved through a panel discussion to complete the interview materials' coding. The coding of interview data was carried out using the NVivo 12 software.

Results

Basic Information on Severe Hospital Violence

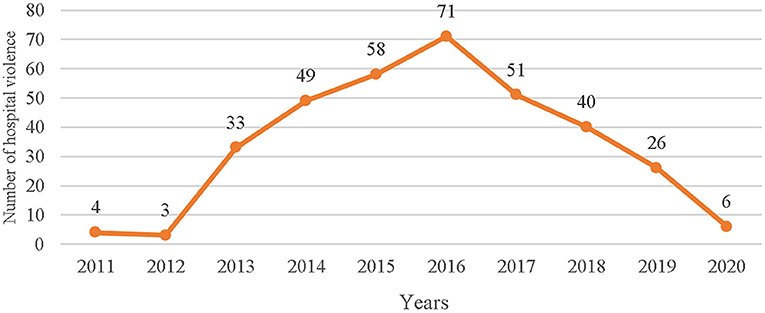

From 2011 to 2020, Chinese courts ruled on a total of 341 hospital violence incidents. China's serious hospital violence showed a trend of first increase and then decrease in the past 10 years (Figure 1). Most of these hospital violence incidents occurred in secondary hospitals (54.3%), outpatient departments (47.8%), and emergency departments (25.2%). Doctors and nurses experienced the highest hospital violence frequency. Most perpetrators commit violence by physically assaulting others, laying wreaths, blocking doors, burning papers, placed the corpse, and pulling banners, among others. The largest number of incidents resulted in hospital property losses, disorders, and minor injuries to medical personnel.

Causes of Hospital Violence

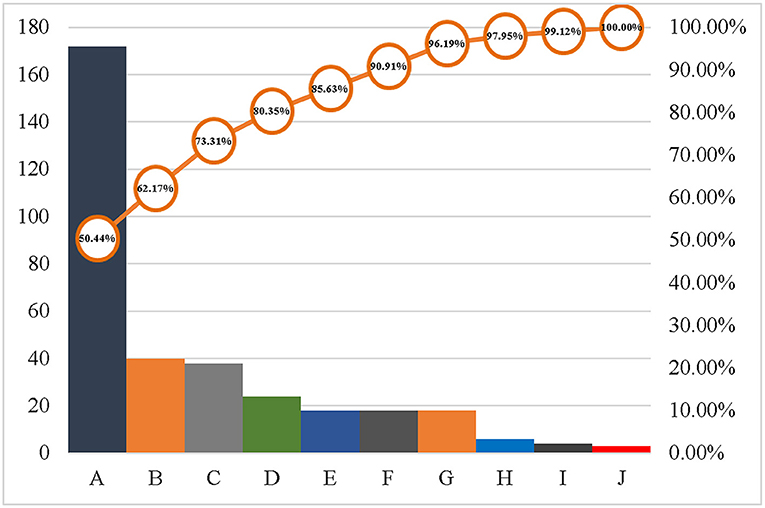

The results showed that the main causes of hospital violence were patients' death (50.44%), dissatisfaction with the treatment effect (11.73%), out-of-hospital disputes (11.14%), and dissatisfaction with the arrangement of healthcare workers (7.04%). In contrast, waiting time and medical expenses were only secondary factors (Figure 2).

Note: A: Patient died; B: Dissatisfied with the effect of treatment; C: Out-of-hospital disputes; D: Dissatisfied with healthcare workers arrangements; E: The patient's unreasonable request was rejected; F: Medical Dispute; G: Attitudes of medical staff; H: other; I: waiting time; J: Medical expenses.

Characteristics of Perpetrators

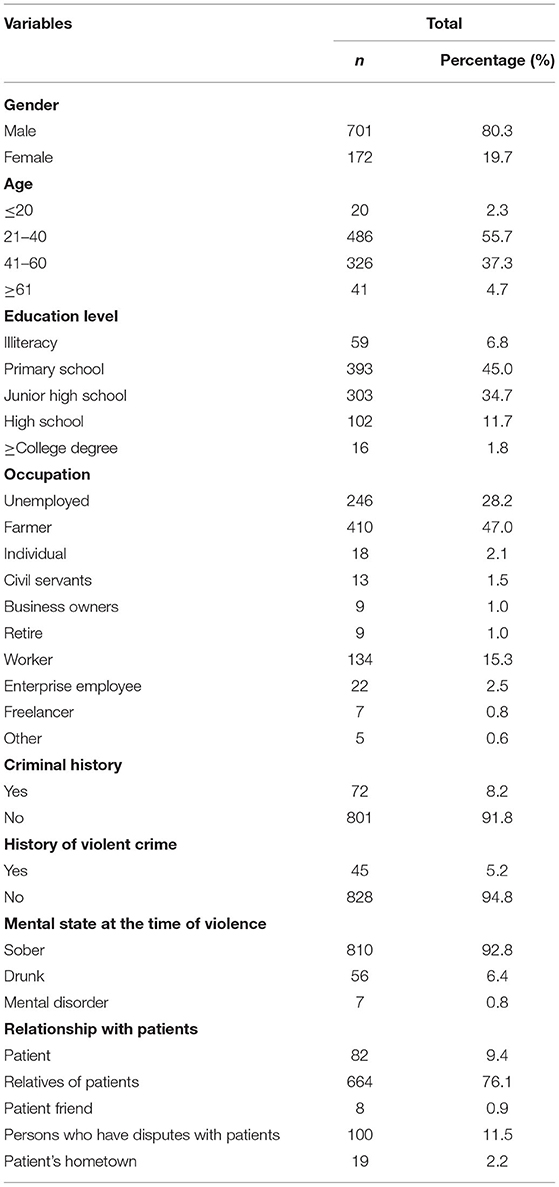

Through an analysis of the perpetrators' characteristics, the researchers found that a vast majority of the 873 perpetrators were men (80.3%), under the age of 40 (58.0%), had attained junior middle school education or below (86.5%), and were farmers or unemployed (85.2%). Seventy-two people had criminal records, of which 45 had a history of violent crimes. The main perpetrators were patients' family members (76.1%) (Table 1).

Hospital Violence Prevention and Control Measures

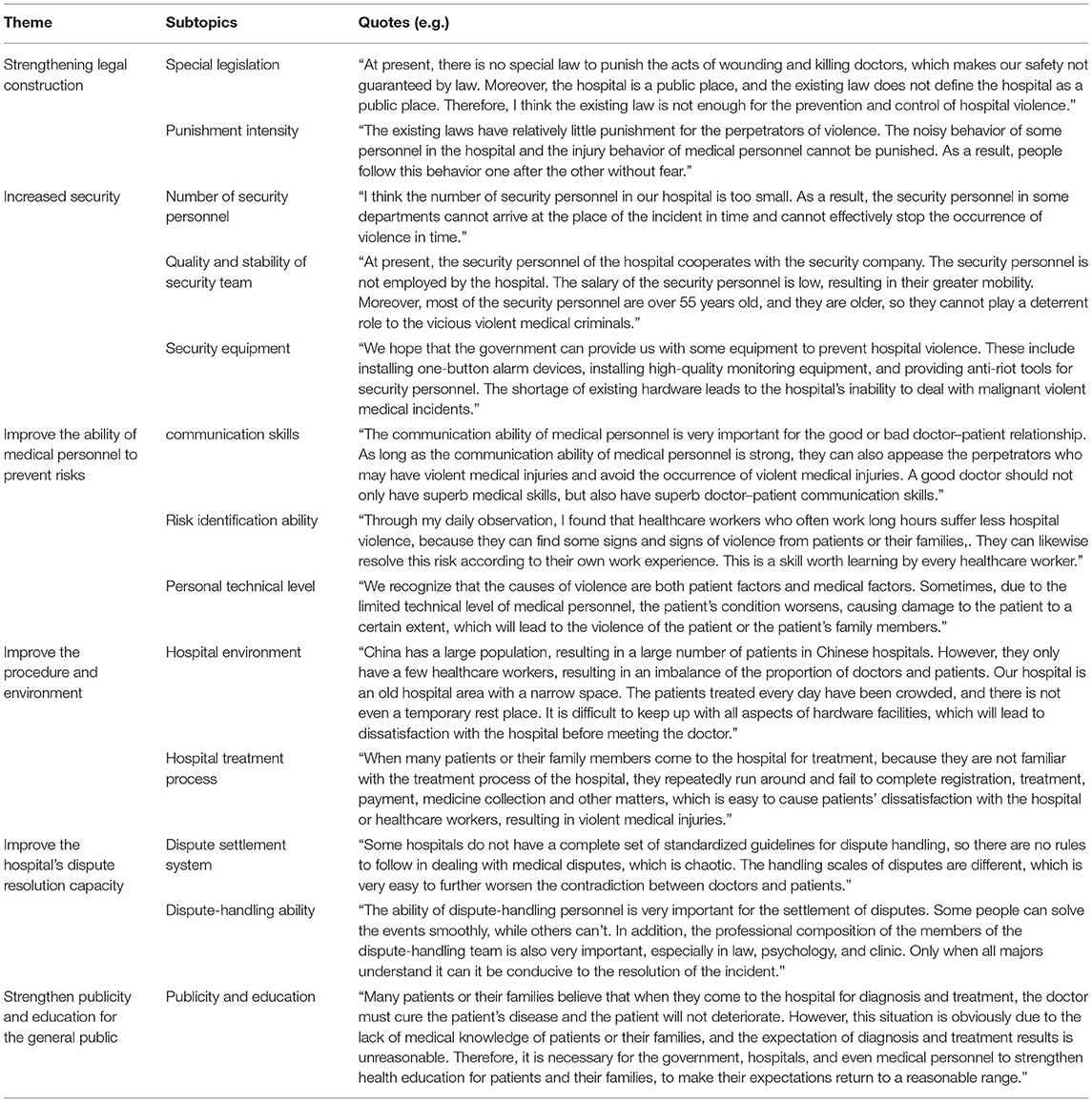

A total of 72 people were interviewed, 33 from secondary hospitals and 39 from tertiary hospitals. Most of them were over 35 years old (55.55%) and had a Bachelor's degree (54.17%). Particularly, there were 16 doctors, 22 nurses, 24 managers, and 10 security guards. The interview results show that frontline medical personnel believe that hospital violence's effective prevention and control at this stage should be carried out from three different aspects. First, the state should make a special legislation to increase the punishment and cost of malignant and violent medical injuries. At the same time, there must be publicity and education for ordinary people to improve their health and legal literacy. Second, hospitals should constantly improve their doctors' diagnoses, treatment, and security ability. Moreover, they must improve their medical dispute-handling team's abilities and that of their dispute-handling personnel. Third, hospitals should train their medical personnel in doctor–patient communication, risk identification abilities, and knowledge and skills. Healthcare workers should also take the initiative to improve their skills to further avoid the occurrence of hospital violence (Table 2).

Discussion

The characteristics of hospital violence events found in this study are consistent with those of previous studies. Most of these cases occurred in secondary hospitals, outpatient departments, and emergency departments (25, 26). Moreover, most perpetrators committed violence by placing wreaths, blocking doors, burning papers, placed the corpse, and physically assaulting others (26, 27). Doctors and nurses experienced the highest frequency of violence (28, 29). The incidents' consequences were mainly minor injuries, property damage, and disorderly disturbances (30, 31). This study will focus on the causes of hospital violence and the characteristics of the perpetrators. It will likewise explore possible hospital violence prevention and control measures to alleviate hospital violence in the future, and provide reference and advice for governments and policy-making bodies involved in creating such measures.

Analysis of the Causes of Hospital Violence

Through an analysis of the causes of violence, we found that patients' deaths and dissatisfaction with treatment effects were the main causes of serious hospital violence. This may be caused by patients' or their families' high expectations regarding the effects of diagnosis and treatment (23, 32). Patients often choose hospitals with a good environment and a high expectation regarding treatment effects. Once the treatment effect is poor, the high expectation brought about by the good environment before the treatment and the low perceived value of patients after the treatment will lead to lower patient satisfaction. This will result in the occurrence of hospital violence (33). However, we should also clearly realize that patients' deaths and poor treatment effects may likewise be caused by medical accidents or errors. It is difficult for patients or their families to accept the damage caused to patients. This too, can easily cause hospital violence.

We also found another main reason for serious hospital violence that has never been mentioned in previous studies: out-of-hospital disputes. The results show that out-of-hospital disputes ranked third among serious hospital violence's main causes. Out-of-hospital disputes refer to disputes between patients and third-party personnel (i.e., non-medical personnel) before admission. Such a dispute may have caused damage to the patient's physical and mental health and may have led to the patient's admission. After the patient is admitted to the hospital, the altercation between the two parties is likely transferred to the hospital or healthcare workers, if it is not reasonably resolved. Thus, the hospital becomes a place for patients to take out their negative emotions. Moreover, such emotions are likely vented out on medical personnel. Hospital managers and healthcare workers should always be vigilant during such cases to avoid the transfer and evolution of contradictions.

Dissatisfaction with healthcare workers' arrangements and the failure to meet patients' unreasonable requirements are also main reasons for the occurrence of hospital violence. In the process of seeing a doctor, patients sometimes refuse to listen to healthcare workers' arrangements or put forward unreasonable requirements due to their own needs. Rejection of unreasonable requirements and environmental factors such as long waiting times, increase the likelihood of patients to engage in violent actions to hurt healthcare workers to express their dissatisfaction.

Medical disputes are doctor–patient contradictions caused by patients' disagreement with the diagnosis and treatment process or results. When the doctors and patients have inconsistent negotiations on the disputes, patients may often recourse to violence to express their dissatisfaction with the entire healthcare system, or with specific doctors (32). Moreover, due to the influence of some media on doctors' “stigmatization” and previous violent medical incidents' success, patients or their families tend to imitate others in committing violence to achieve their own goals.

Dissatisfaction with healthcare workers' attitudes is also a main cause of hospital violence. Healthcare workers' attitude problems is in the final analysis of communication problems between doctors and patients. At present, the government and hospitals are carrying out only a few doctor–patient communication trainings for healthcare workers. Moreover, there is a lack of human resources, resulting in the heavy medical tasks undertaken by medical personnel every day. As such, there is a lack of opportunity and sufficient time to receive relevant training. This may result in healthcare workers' insufficient humanistic care for patients and lack of empathy. This will further lead to poor effects of doctor–patient communication. When the patient believes that healthcare workers have a poor attitude toward them, hospital violence may occur (23). Research has proven that strengthening humanistic medical education and improving healthcare workers' humanistic medical literacy can effectively promote trust between doctors and patients. This will likewise reduce the conflict between doctors and patients (34).

Long waiting times and high medical expenses have always been important reasons behind violence committed by patients. However, we believe that the hospital violence caused by long waiting times and high medical expenses will gradually decrease with the increasing investment of the Chinese government in the health sector and the continuous improvement of the medical insurance system and the hierarchical diagnosis and treatment system.

Analysis of the Characteristics of Perpetrators

Through a study of the relevant characteristics of 873 perpetrators, it was found that most of the perpetrators were male, 21–40 years old, with junior high school level education or below, and were farmers or unemployed. This finding consistent with previous research results (35, 36). Patients or their families with such characteristics have a low level of overall health literacy and often have high expectations from medical procedures or treatment results. They are more inclined to take extreme violence to vent their negative emotions and exert pressure on the hospital when their expectations or requirements are not met. Furthermore, according to the neutralization theory, “the attraction of higher loyalty obligation is one of the factors that neutralizes internal control and external control and makes the offender embark on the road of misconduct. The perpetrators claim that their actions are in line with the moral obligations of their group, leading to the ineffectiveness of internal control (i.e., self-factors restraining criminal acts) and external control (i.e., social factors restraining criminal acts)” (37). Therefore, people with low educational backgrounds and poor cognitive levels may have a higher sense of identity for group behavior. Similarly, they are more likely to be coerced by the group to resort to violent injury behavior.

The results show that some perpetrators have criminal records and a history of violent crimes. Based on previous studies, it is generally believed that a history of violent crimes is the main factor in predicting patients' or their families' hospital behavior (38–40). Therefore, medical personnel should pay attention to personnel with such characteristics in the process of preventing and controlling hospital violence. However, because the police system is not connected to the hospital system, it is difficult for healthcare workers to judge whether the patient or their family has a criminal record.

The study also found that drunkenness or mental disorders may also be characteristics of violent perpetrators in hospitals. This is consistent with previous research results (36, 40). When patients or their families are not satisfied with the work of healthcare workers or the hospital's diagnosis and treatment process, those in a state of drunkenness or having mental disorders are more impulsive and difficult to control. This results to their violent acts toward healthcare workers.

We also found that most perpetrators were patients' relatives, further confirming previous research (26). We believe that this is caused by a lack of empathy of patients' relatives toward the doctor. Such an inducement lies in their in-group identity. As a social primate, it is instinctual for a man to rely on his group for survival. Under the control of this instinct, people stay close to their group, and trust those in the same group to help and protect each other. However, there is relative indifference to other groups they do not belong to. Moreover, they may be hostile toward individuals or groups that infringe on the interests of their own group. In cases of hospital violence, patients' relatives often consider healthcare workers as parties infringing on their group interests just because their expectations are not fully met. As such, they do not empathize with these healthcare workers and even resort to perpetrating violent injury against them. Healthcare workers also have the same problem. The lack of empathy among healthcare workers leads them to ignore the demands of patients. This results in the creation and escalation of doctor–patient contradictions, leading to further occurrences of hospital violence.

Analysis of Hospital Violence Prevention and Control Measures

The harm caused by hospital violence to hospitals, healthcare workers, and the national health system cannot be ignored. All concerned parties should continue to pay attention to this problem and take active measures to curb the occurrence of violent medical injuries. This study puts forward the following specific measures based on the analysis of the characteristics of serious hospital violence incidents, in-depth interviews with frontline health workers and managers, and the actual situation of hospital violence prevention and control in China. These measures will help provide a reference for the effective prevention and control of hospital violence.

Develop a Hospital Workplace Violence Risk Reporting System

Davide Ferorelli evaluated the incident reporting system for clinical risk management and found that the system can effectively reduce litigation between doctors and patients (41). At the same time, the scholar also proposed corresponding clinical risk management methods to measure the risk of psychiatric violence (42). Hospital violence also requires clinical risk management. The occurrence of such incidents is not without warning. There must be some omens and signs before the incident. Hospital managers and researchers should develop and improve the risk reporting system of hospital violence by summarizing the causes and precursors of hospital violence in the future. The corresponding risk prevention tools help to timely identify the risk of violent incidents and take targeted preventive measures to avoid such incidents.

Continuing to Reform the Medical and Health System and Increasing Investments in the Health Sector

The occurrence of hospital violence partly reflects the disadvantages of China's medical and health systems. For example, inadequate health system investments result in insufficient training costs for medical personnel. Moreover, it becomes difficult to pay expensive remuneration for their services. This leads to medical malpractice, corruption, poor communication between doctors and patients, and hospital violence (43). Therefore, the government should increase investments in the health sector and improve the quality of medical services. Through systematic reform, the government and hospitals can ease the dispute between doctors and patients and reduce the occurrence of hospital violence (27).

Improving the Legal System Construction Against Hospital Violence

The law is an effective means of regulating violence. Although China has successively issued relevant laws and regulations for dealing with hospital violence (6), the punishment for perpetrators is light, and the effect of deterring criminals from committing crimes is limited. Thus, using the other countries' experience as a basis, China should make special legislations on hospital violence. They must also distinguish the punishment for hospital violence from those for other forms of general violence and impose stricter punishments. This will help China achieve the purpose of warning and regulation.

Strengthening the Publicity and Education of the General Public's Concept of the Health and Legal System

The gradual enhancement of patients' awareness of their rights and improving their understanding of medical services' particularity will exacerbate the conflict between doctors and patients. The state should pay attention to the popularization and education of people's basic health and medical knowledge through media publicity and community education. Through this, patients will have a clearer and reasonable understanding of their diseases and will be able to more easily accept the adverse effects of such diseases (44). At the same time, legal education for the masses should be strengthened to reduce their criminal motives.

Strengthening the Security Force of the Hospital

Security guards are an important force for maintaining law and order in the hospital. However, Chinese hospitals' security are generally weak. Security personnel's characteristics such as old age, poor treatment, and high mobility result in their ineffective response to security threats. They may even choose to escape when violence occurs in the hospital. Therefore, a younger security team and improvements in security personnel's treatment and overall quality are crucial for Chinese hospitals to prevent and control workplace violence. At the same time, using digital information in response to security forces' deficiencies is also an effective measure that the hospital can adopt during instances of hospital violence. Strengthening hospital security capacity is crucial in preventing the occurrence of violence after effectively identifying their characteristics.

Improving the Dispute-Handling System and the Dispute-Handling Ability of Personnel

Personnel's personal ability in dispute handling, the hospital dispute-handling team's abilities, and the national medical dispute-handling system's establishment and improvement are crucial to avoid the occurrence of hospital violence (27). The improvement of the dispute-handling system and personnel's dispute-handling abilities can effectively prevent the occurrence of violent medical injuries caused by the failure of doctor–patient negotiations on controversial issues.

Improving the Hospital Treatment Process and Environment

Patients' awareness of their rights is being gradually strengthened and their requirements for medical experience are increasing with society's development. The hospital treatment environment and the treatment process' complexity directly affect the patients' intuitive feelings toward hospitals. Previous studies have shown that improvements in the hospital environment, such as setting clear department instruction signs, creating a clean and comfortable environment, and implementing a convenient medical treatment process can improve patients' medical experience. These will improve patient satisfaction and reduce the likelihood of disputes (40). Therefore, in the process of hospital management, hospital managers should constantly optimize the hospital's diagnosis and treatment process and create a harmonious and orderly treatment environment. They must likewise avoid affecting patients' medical experience and healthcare personnel's working mood brought about by the complexity and noise of the diagnosis and treatment process, which can result in hospital violence.

Improving the Self-Protection Awareness and Ability of Healthcare Workers

Training can effectively prevent hospital violence occurrence (45). Hospitals should provide various forms of training to healthcare workers. These include training and lectures to improve medical personnel's doctor–patient communication abilities, hospital violence risk identification and response abilities, and medical technology levels. At the same time, emergency drills should be actively carried out to prevent and control hospital violence. This will improve medical personnel's prevention and control awareness. Medical personnel should also actively study hard, participate in trainings, and apply the learned skills to practice. They can effectively protect themselves from violence by identifying the risk of violence according to the characteristics of violent events and perpetrators, taking the initiative to avoid danger, and taking preventive measures.

Limitations

This study had three limitations. First, Due to the delay in court judgment, some violent medical incidents that have occurred have still not been judged by the court. Thus, they were not included in the scope of the study. Second, the occurrence of serious violent medical trauma may be a result of a joint action of multiple factors. The variables involved in this study were limited. As such, some confounding factors were not considered. Therefore, further studies are required in the future. Third, the selected interviewees included only the hospitals' relevant personnel. In the future, government personnel and university researchers should be included in the research to achieve more comprehensive and systematic prevention and control measures. Lastly, convenience sampling is not suitable for general inference.

Conclusions

The frequency of serious hospital violence events in China is still high. Hospital violence is mostly caused by patient death, dissatisfaction with treatment, and out-of-hospital disputes. These disputes are closely related to the gender, age, education, occupation, and other characteristics of the perpetrator. All concerned parties should take new measures from the aspects of legislation, security, dispute-handling systems, and capacity building to prevent and control the occurrence of hospital violence. Medical personnel should also improve their protection awareness and risk prevention ability. Furthermore, they must take advanced preventive and control measures according to patients' characteristics to protect themselves from violence.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: If necessary, the data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Lihua Fan, lihuafan@126.com.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health of Harbin Medical University (Project Identify Code: HMUIRB20180305). Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

YM participated in study design and conception, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript drafting, and funding acquisition. LW and YW participated in data acquisition. ZL and YZ participated in the design and conceptualization of the study, acquisition of data, and data interpretation. LF and XN participated in the design and conceptualization of study, acquisition of data, revising of the manuscript, acquisition of funding, and supervision. All authors were involved in the manuscript's revision and approved this final version.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant Number 71874043. The funders had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants, public health institutions, and cooperative colleges in this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.783137/full#supplementary-material

References

1. ISBN. Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Geneva: Switzerland Ilo (2002).

2. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. New Engl J Med. (2016) 374:1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501998

4. Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. (2019) 76:927–37. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2019-105849

6. Lu S, Ren S, Xu Y, Lai J, Hu J, Lu J, et al. China legislates against violence to medical workers. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30005-5

7. Chinanews. A Suspected Explosive Deflagration Incident in a Hangzhou Hospital Caused 4 Injuries and Suspects were Under Control, Beijing: China News Service (2021).

8. Shi L, Zhang D, Zhou C, Yang L, Sun T, Hao T, et al. A cross-sectional study on the prevalence and associated risk factors for workplace violence against Chinese nurses. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013105. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013105

9. Li Z, Yan CM, Shi L, Mu HT, Li X, Li AQ, et al. Workplace violence against medical staff of Chinese children's hospitals: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0179373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179373

10. Hedayati Emam G, Alimohammadi H, Zolfaghari Sadrabad A, Hatamabadi H. Workplace violence against residents in emergency department and reasons for not reporting them; a cross sectional study. Emerg (Tehran). (2018) 6:e7. doi: 10.22037/emergency.v6il.19430

11. Kumar M, Verma M, Das T, Pardeshi G, Kishore J, Padmanandan A. A study of workplace violence experienced by doctors and associated risk factors in a tertiary care hospital of South Delhi, India. J Clin Diagn Res. (2016) 10:Lc06–10 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22306.8895

12. Berlanda S, Pedrazza M, Fraizzoli M, de Cordova F. Addressing risks of violence against healthcare staff in emergency departments: the effects of job satisfaction and attachment style. Biomed Res Int. (2019) 2019:5430870. doi: 10.1155/2019/5430870

13. Jaradat Y, Nielsen MB, Kristensen P, Nijem K, Bjertness E, Bast-Pettersen R. Mental distress and job satisfaction in Palestinian nurses exposed to workplace aggression: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. (2018) 391:S37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30362-3

14. Zhao S, Xie F, Wang J, Shi Y, Fan L. Prevalence of workplace violence against chinese nurses and its association with mental health: a cross-sectional survey. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2018) 32:242–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.11.009

15. Ma Y, Wang Y, Shi Y, Shi L, Wang L, Li Z, et al. Mediating role of coping styles on anxiety in healthcare workers victim of violence: a cross-sectional survey in China hospitals. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e048493. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048493

16. Fang H, Zhao X, Yang H, Sun P, Li Y, Jiang K, et al. Depressive symptoms and workplace-violence-related risk factors among otorhinolaryngology nurses and physicians in Northern China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019514. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019514

17. Li X, Wu H. Does psychological capital mediate between workplace violence and depressive symptoms among doctors and nurses in Chinese General Hospitals? Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:199–206. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S293843

18. Liu J, Zheng J, Liu K, Liu X, Wu Y, Wang J, et al. Workplace violence against nurses, job satisfaction, burnout, and patient safety in Chinese hospitals. Nurs Outlook. (2019) 67:558–66. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.04.006

19. Aytac S, Bozkurt V, Bayram N, Yildiz S, Aytac M, Akinci FS, et al. Workplace violence: a study of Turkish workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. (2011) 17:385–402. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2011.11076902

20. He AJ. The doctor-patient relationship, defensive medicine and overprescription in Chinese public hospitals: evidence from a cross-sectional survey in Shenzhen city. Soc Sci Med. (2014) 123:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.055

21. Wei CY, Chiou ST, Chien LY, Huang N. Workplace violence against nurses–prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2016) 56:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.12.012

22. Roberts and Dexter. Two-Thirds of Chinese Don't Trust Doctors, Amid Rising Hospital Violence. BusinessWeek.com:9-9 New York: Business Week (2013).

23. Tucker JD, Cheng Y, Wong B, Gong N, Nie JB, Zhu W, et al. Patient-physician mistrust and violence against physicians in Guangdong Province, China: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008221. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008221

24. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

25. Tian Y, Yue Y, Wang J, Luo T, Li Y, Zhou J. Workplace violence against hospital healthcare workers in China: a national WeChat-based survey. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:582. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08708-3

26. Liu Y, Zhang M, Li R, Chen N, Huang Y, Lv Y, et al. Risk assessment of workplace violence towards health workers in a Chinese hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e042800. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042800

27. Hesketh T, Wu D, Mao L, Ma N. Violence against doctors in China. BMJ. (2012) 345:e5730. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5730

28. Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Violence towards health care workers in a Public Health Care Facility in Italy: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12:108. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-108

29. Sun P, Zhang X, Sun Y, Ma H, Jiao M, Xing K, et al. Workplace violence against health care workers in North Chinese Hospitals: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:96. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010096

30. Cai R, Tang J, Deng C, Lv G, Xu X, Sylvia S, et al. Violence against health care workers in China, 2013-2016: evidence from the national judgment documents. Hum Resour Health. (2019) 17:103 doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0440-y

31. Ma J, Chen X, Zheng Q, Zhang Y, Ming Z, Wang D, et al. Serious workplace violence against healthcare providers in China between 2004 and 2018. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:574765. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574765

32. Violence against doctors: Why China? Why now? What next? Lancet. (2014) 383:1013. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60501-8

33. Baolong M, Zhichen H, Yaru L Hong W. Causes of medical violence by patients based on QCA. J Beijing Inst Technol (Social Sci Ed). (2019) 5:101–14. doi: 10.15918/j.jbitss1009-3370.2019.105

34. Dossett ML, Kohatsu W, Nunley W, Mehta D, Davis RB, Phillips RS Yeh G, et al. medical student elective promoting humanism, communication skills, complementary and alternative medicine and physician self-care: an evaluation of the HEART program. Explore (NY). (2013) 9:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2013.06.003

35. Li N, Wang Z, Dear K. Violence against health professionals and facilities in China: evidence from criminal litigation records. J Forensic Leg Med. (2019) 67:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.07.006

36. James A. Violence and aggression in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. (2006) 23:431–4. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.028621

37. Maruna S, Copes H. What have we learned from five decades of neutralization research? Crime Just. (2005) 32:221–320. doi: 10.1086/655355

38. Kling R, Corbière M, Milord R, Morrison JG, Craib K, Yassi A, et al. Use of a violence risk assessment tool in an acute care hospital: effectiveness in identifying violent patients. AAOHN J. (2006) 54:481–7. doi: 10.1177/216507990605401102

39. Forster JA, Petty MT, Schleiger C, Walters HC. kNOw workplace violence: developing programs for managing the risk of aggression in the health care setting. Med J Aust. (2005) 183:357–61. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07083.x

40. Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Miller M, Howard PK. Workplace violence in healthcare settings: risk factors and protective strategies. Rehabil Nurs. (2010) 35:177–84. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00045.x

41. Ferorelli D, Solarino B, Trotta S, Mandarelli G Dell'Erba A. Incident reporting system in an Italian University Hospital: a new tool for improving patient safety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:267. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176267

42. Ferorelli D, Mandarelli G, Zotti F, Ferracuti S, Carabellese F, Solarino B, et al. Violence in forensic psychiatric facilities. A risk management perspective. J Psychopathol. (2021) 27:40–50. doi: 10.36148/2284-0249-419

43. Ending violence against doctors in China. Lancet. (2012) 379:1764. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60729-6

44. Wang XQ, Wang XT, Zheng JJ. How to end violence against doctors in China. Lancet. (2012) 380:647–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61367-1

Keywords: hospital violence, healthcare workers, perpetrators, prevention and control measures, China, characteristics and measures

Citation: Ma Y, Wang L, Wang Y, Li Z, Zhang Y, Fan L and Ni X (2022) Causes of Hospital Violence, Characteristics of Perpetrators, and Prevention and Control Measures: A Case Analysis of 341 Serious Hospital Violence Incidents in China. Front. Public Health 9:783137. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.783137

Received: 25 September 2021; Accepted: 08 December 2021;

Published: 07 January 2022.

Edited by:

Helena C. Maltezou, National Public Health Organization (EHEA), GreeceReviewed by:

Davide Ferorelli, University of Bari Medical School, ItalyJing Ma, Second People's Hospital of Hunan Province, China

Copyright © 2022 Ma, Wang, Wang, Li, Zhang, Fan and Ni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lihua Fan, lihuafan@126.com; Xin Ni, nixin@bch.com.cn

Yuanshuo Ma1

Yuanshuo Ma1 Yafeng Zhang

Yafeng Zhang Lihua Fan

Lihua Fan Xin Ni

Xin Ni