Salivary Biomarkers and Their Application in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of the Most Common Oral Pathologies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

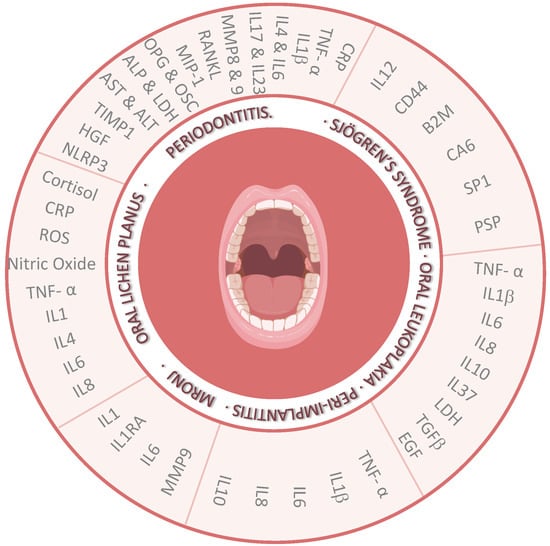

2. Biomarkers in Saliva in Different Oral Diseases

2.1. Oral Lichen Planus

2.2. Periodontitis

2.3. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome

2.4. Oral Leukoplakia

2.5. Peri-Implantitis

2.6. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSCC | oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| ILs | interleukins |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| OLP | oral lichen planus |

| PD | periodontitis |

| pSS | primary Sjögren’s syndrome |

| MRONJ | medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor α |

| Th | T-helper |

| IL-2R | IL-2 receptor |

| TRIM21 | tripartite motif-containing 21 |

| RANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| OPG | osteoprotegerin |

| OSC | osteocalcin |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteases |

| TIMP-1 | tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1 |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| NLRP3 | nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing protein 3 |

| SP-1 | salivary protein-1 |

| PSP | parotid secretory protein |

| CA-6 | carbonic anhydrase VI |

| TGFβ | transforming growth factor β |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| BPs | bisphosphonates |

| IL-1RA | interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

References

- Wu, J.Y.; Yi, C.; Chung, H.R.; Wang, D.J.; Chang, W.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Lin, C.T.; Yang, Y.C.; Yang, W.C.V. Potential biomarkers in saliva for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010, 46, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, F.I.; Sheth, C.C.; Veses, V. Salivary biomarkers and their efficacies as diagnostic tools for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Sankhla, B.; Sundaragiri, K.S.; Bhargava, A. A Review of Salivary Biomarker: A Tool for Early Oral Cancer Diagnosis. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2017, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.; McCullough, M. Chemokines and Cytokines as Salivary Biomarkers for the Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer. Int. J. Dent. 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.-Z.; Cheng, X.Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhang, P.; Yi, P.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X.-D. Saliva in the diagnosis of diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 8, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Martínez, P.M. La saliva como fluido diagnóstico. Ed. Cont. Lab. Clín. 2013, 16, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Berga-Hidalgo, M.C. Marcadores Salivales en Lesiones Potencialmente Malignas de la Cavidad oral y en Carcinoma oral de Células Escamosas; Ed Cont Lab Clín Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Wong, D.T. Saliva: An emerging biofluid for early detection of diseases. Am. J. Dent. 2009, 22, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Wen, S.W.; Liu, A. Salivary cortisol in post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, S.; Santos, E.; Gaztambide, S.; Salvador, J. Diagnóstico y diagnóstico diferencial del síndrome de Cushing. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2009, 56, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, V.; Jones, J.; Wehler, C. Salivary biomarkers and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018, 56, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, M.R.; Soldini, L.; Vidoni, G.; Mabellini, C.; Belloni, T.; Brignolo, L.; Negri, S.; Schlusnus, K.; Dorigatti, F.; Lazzarin, A. Point-of-care testing for HCV infection: Recent advances and implications for alternative screening. New Microbiol. 2014, 37, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nefzi, F.; Ben Salem, N.A.; Khelif, A.; Feki, S.; Aouni, M.; Gautheret-Dejean, A. Quantitative analysis of human herpesvirus-6 and human cytomegalovirus in blood and saliva from patients with acute leukemia. J. Med. Virol. 2014, 87, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, J.P.; Ortiz, C.; Morales-Bozo, I.; Rojas-Alcayaga, G.; Baeza, M.; Beltran, C.; Escobar, A. α-2-Macroglobulin in Saliva Is Associated with Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Dis. Markers 2015, 2015, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rathnayake, N.; Åkerman, S.; Klinge, B.; Lundegren, N.; Jansson, H.; Tryselius, Y.; Sorsa, T.; Gustafsson, A. Salivary Biomarkers for Detection of Systemic Diseases. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Jornet, P.; Zavattaro, E.; Mozaffari, H.R.; Ramezani, M.; Sadeghi, M. Evaluation of the Salivary Level of Cortisol in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2019, 55, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopez-Jornet, P.; Cayuela, C.A.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Escribano, D.; Cerón, J.; Parra-Perez, F. Oral lichen planus: Salival biomarkers cortisol, immunoglobulin A, adiponectin. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 45, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humberto, J.S.M.; Pavanin, J.V.; Da Rocha, M.J.A.; Motta, A.C.F. Cytokines, cortisol, and nitric oxide as salivary biomarkers in oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Ashok, L.; Sujatha, G. Evaluation of salivary cortisol and psychological factors in patients with oral lichen planus. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2009, 20, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, P.; Aswath, N. Stress as an etiologic co-factor in recurrent aphthous ulcers and oral lichen planus. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 58, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Aznar-Cayuela, C.; Rubio, C.P.; Ceron, J.J.; López-Jornet, P.; Asta, T.; Cristina, A.C.; Camila, P.R.; Joaquin, C.J. Evaluation of salivary oxidate stress biomarkers, nitric oxide and C-reactive protein in patients with oral lichen planus and burning mouth syndrome. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2016, 46, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, M.; Iwase, M.; Nagumo, M. Elevated production of salivary nitric oxide in oral mucosal diseases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1999, 28, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darczuk, D.; Krzysciak, W.; Vyhouskaya, P.; Kesek, B.; Galecka-Wanatowicz, D.; Lipska, W.; Kaczmarzyk, T.; Gluch-Lutwin, M.; Mordyl, B.; Chomyszyn-Gajewska, M. Salivary oxidative status in patients with oral lichen planus. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Pol. Physiol. Soc. 2016, 67, 885–894. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, M.; Jafari, S.; Barati, M.; Mahdipour, M.; Gholami, M.S. Predictive value of salivary microRNA-320a, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, CRP and IL-6 in Oral lichen planus progression. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, A.; Arab, S.; Mousavi, S.J.; Zamanian, A.; Maboudi, A. Serum and Salivary Level of Nitric Oxide (NOx) and CRP in Oral Lichen Planus (OLP) Patients. J. Dent. Shiraz 2020, 21, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ramseier, C.A.; Kinney, J.S.; Herr, A.E.; Braun, T.; Sugai, J.V.; Shelburne, C.A.; Rayburn, L.A.; Tran, H.M.; Singh, A.K.; Giannobile, W.V. Identification of Pathogen and Host-Response Markers Correlated with Periodontal Disease. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrchen, J.M.; Sunderkötter, C.; Foell, D.; Vogl, T.; Roth, J. The endogenous Toll-like receptor 4 agonist S100A8/S100A9 (calprotectin) as innate amplifier of infection, autoimmunity, and cancer. J. Leukoc. Boil. 2009, 86, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurer, A.; Aurer-Kozelj, J.; Stavljenić-Rukavina, A.; Kalenić, S.; Ivić-Kardum, M.; Haban, V. Inflammatory mediators in saliva of patients with rapidly progressive periodontitis during war stress induced incidence increase. Coll. Antropol. 1999, 23, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Aurer, A.; Jorgić-Srdjak, K.; Plancak, D.; Stavljenić-Rukavina, A.; Aurer-Kozelj, J. Proinflammatory factors in saliva as possible markers for periodontal disease. Coll. Antropol. 2005, 29, 435–439. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, H.R.; Ramezani, M.; Mahmoudiahmadabadi, M.; Omidpanah, N.; Sadeghi, M. Salivary and serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2017, 124, e183–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Du, G.; Zhou, G. Inflammation-related cytokines in oral lichen planus: An overview. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2013, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanthoni, M.; Sathasivasubramanian, S. Quantitative Analysis of Salivary TNF-αin Oral Lichen Planus Patients. Int. J. Dent. 2015, 2015, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frodge, B.D.; Ebersole, J.L.; Kryscio, R.J.; Thomas, M.V.; Miller, C.S. Bone Remodeling Biomarkers of Periodontal Disease in Saliva. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Ning, L.; Tu, Y.; Huang, C.-P.; Huang, N.-T.; Chen, Y.-F.; Chang, P.-C. Salivary biomarker combination prediction model for the diagnosis of periodontitis in a Taiwanese population. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018, 117, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J. Cytokine regulation of immune responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontology 2000 2010, 54, 160–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preshaw, P.; Taylor, J. How has research into cytokine interactions and their role in driving immune responses impacted our understanding of periodontitis? J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersole, J.; Schuster, J.L.; Stevens, J.; Dawson, D.; Kryscio, R.J.; Lin, Y.; Thomas, M.V.; Miller, C.S. Patterns of Salivary Analytes Provide Diagnostic Capacity for Distinguishing Chronic Adult Periodontitis from Health. J. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 33, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, N.; Åkerman, S.; Klinge, B.; Lundegren, N.; Jansson, H.; Tryselius, Y.; Sorsa, T.; Gustafsson, A. Salivary biomarkers of oral health—A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 40, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepthi, G.; Nandan, S.R.K.; Kulkarni, P.G. Salivary Tumour Necrosis Factor-α as a Biomarker in Oral Leukoplakia and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaur, J.; Jacobs, R. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in oral lichen planus, oral leukoplakia, and oral submucous fibrosis. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 41, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, H.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Shieh, T.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Kao, Y.-H.; Yang, C.F.; Ko, E. Role of cytokine gene (interferon-γ, transforming growth factor-β1, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10) polymorphisms in the risk of oral precancerous lesions in Taiwanese. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brailo, V.; Vucicevic-Boras, V.; Lukac, J.; Biocina-Lukenda, D.; Alajbeg, I.; Milenovic, A.; Balija, M. Salivary and serum interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with leukoplakia and oral cancer. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2011, 17, e10–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenghoefer, M.; Pantelis, A.; Najafi, T.; Deschner, J.; Allam, J.; Novak, N.; Reich, R.; Martini, M.; Berge, S.; Fischer, H.; et al. Gene expression of oncogenes, antimicrobial peptides, and cytokines in the development of oral leukoplakia. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2010, 110, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduljabbar, T.; Vohra, F.; Ullah, A.; Alhamoudi, N.; Khan, J.; Javed, F. Relationship between self-rated pain and peri-implant clinical, radiographic and whole salivary inflammatory markers among patients with and without peri-implantitis. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Bujanda, N.; Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Blanco-Pintos, T.; Alonso-Sampedro, M.; Relvas, M.; González-Peteiro, M.M.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Tomás, I.; Sampedro-Alonso, M. Diagnostic accuracy of IL1β in saliva: The development of predictive models for estimating the probability of the occurrence of periodontitis in non-smokers and smokers. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, R.; Yeltiwar, R.K.; Pushpanshu, K. Salivary Interleukin-1β Levels in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis before and after Periodontal Phase I Therapy and Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. J. Periodontol. 2011, 82, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirrielees, J.; Crofford, L.J.; Lin, Y.; Kryscio, R.J.; Dawson, L.R.; Ebersole, J.L.; Miller, C.S. Rheumatoid arthritis and salivary biomarkers of periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürsoy, U.K.; Könönen, E.; Uitto, V.-J.; Pussinen, P.; Hyvärinen, K.; Knuuttila, M.; Suominen-Taipale, L. Salivary interleukin-1βconcentration and the presence of multiple pathogens in periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobón-Arroyave, S.I.; Jaramillo-González, P.; Isaza-Guzman, D.M. Correlation between salivary IL-1β levels and periodontal clinical status. Arch. Oral Boil. 2008, 53, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assuma, R.; Oates, T.; Cochran, D.; Amar, S.; Graves, D.T. IL-1 and TNF antagonists inhibit the inflammatory response and bone loss in experimental periodontitis. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Barksby, H.E.; Lea, S.R.; Preshaw, P.M.; Taylor, J. The expanding family of interleukin-1 cytokines and their role in destructive inflammatory disorders. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007, 149, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, P.Y.B.; Donley, M.; Hausmann, E.; Hutson, A.D.; Rossomando, E.F.; Scannapieco, F. Candidate salivary biomarkers associated with alveolar bone loss: Cross-sectional and in vitro studies. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 49, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liukkonen, J.; Gursoy, U.K.; Pussinen, P.J.; Suominen, A.L.; Könönen, E. Salivary Concentrations of Interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-17A, and IL-23 Vary in Relation to Periodontal Status. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaza-Guzman, D.M.; Medina-Piedrahíta, V.M.; Gutiérrez-Henao, C.; Tobón-Arroyave, S.I. Salivary Levels of NLRP3 Inflammasome-Related Proteins as Potential Biomarkers of Periodontal Clinical Status. J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, F.S.; Jesus, R.N.R.; Rocha, F.M.S.; Moura, C.C.G.; Zanetta-Barbosa, D. Saliva Versus Peri-implant Inflammation: Quantification of IL-1β in Partially and Totally Edentulous Patients. J. Oral Implant. 2014, 40, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.; Smith, D.E. The IL-1 family: Regulators of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Lamacchia, C.; Palmer, G. IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagan, J.; Sheth, C.C.; Soria, J.M.; Margaix, M.; Bagan, L. Bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A preliminary study of salivary interleukins. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2012, 42, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagan, J.; Sáez, G.; Tormos, M.; Hens, E.; Terol, M.; Bagan, L.; Diaz-Fernandez, J.; Lluch, A.; Camps, C. Interleukin-6 concentration changes in plasma and saliva in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Dis. 2013, 20, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, H.R.; Zavattaro, E.; Saeedi, M.; Lopez-Jornet, P.; Sadeghi, M.; Safaei, M.; Imani, M.M.; Nourbakhsh, R.; Moradpoor, H.; Golshah, A.; et al. Serum and salivary interleukin-4 levels in patients with oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, H.R.; Molavi, M.; López-Jornet, P.; Sadeghi, M.; Safaei, M.; Imani, M.; Sharifi, R.; Moradpoor, H.; Golshah, A.; Jamshidy, L. Salivary and Serum Interferon-Gamma/Interleukin-4 Ratio in Oral Lichen Planus Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2019, 55, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prakasam, S.; Srinivasan, M. Evaluation of salivary biomarker profiles following non-surgical management of chronic periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2013, 20, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man Gu, G.; Martin, M.D.; Darveau, R.P.; Truelove, E.; Epstein, J. Oral and serum IL-6 levels in oral lichen planus patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2004, 98, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Guo, B. The relationship between levels of salivary and serum interleukin-6 and oral lichen planus. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 743–749.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-S.L.; Jordan, L.; Gorugantula, L.M.; Schneiderman, E.; Chen, H.-S.; Rees, T. Salivary Interleukin-6 and -8 in Patients with Oral Cancer and Patients with Chronic Oral Inflammatory Diseases. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.P.; Trevisan, G.L.; Macedo, G.O.; Palioto, D.B.; De Souza, S.L.S.; Grisi, M.F.; Novaes, A.B.; Taba, M.; Taba, M., Jr. Salivary Interleukin-6, Matrix Metalloproteinase-8, and Osteoprotegerin in Patients with Periodontitis and Diabetes. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teles, R.; Likhari, V.; Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D. Salivary cytokine levels in subjects with chronic periodontitis and in periodontally healthy individuals: A cross-sectional study. J. Periodontal Res. 2009, 44, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irwin, C.R.; Myrillas, T.T. The role of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 2008, 4, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartold, P.M.; Narayanan, A.S. Molecular and cell biology of healthy and diseased periodontal tissues. Periodontology 2000 2006, 40, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juretić, M.; Cerović, R.; Belušić-Gobić, M.; Pršo, I.B.; Kqiku, L.; Špalj, S.; Pezelj-Ribarić, S. Salivary levels of TNF-? and IL-6 in patients with oral premalignant and malignant lesions. Folia Boil. 2013, 59, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Selvam, N.P.; Sadaksharam, J. Salivary interleukin-6 in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 11, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punyani, S.R.; Sathawane, R.S. Salivary level of interleukin-8 in oral precancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 17, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.P.; Kao, H.K.; Wu, C.C.; Fang, K.H.; Chang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.C.; Liu, S.C.; Cheng, M.H. Pretreatment Interleukin-6 Serum Levels Are Associated with Patient Survival for Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2013, 148, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liskmann, S.; Vihalemm, T.; Salum, O.; Zilmer, K.; Fischer, K.; Zilmer, M. Correlations between clinical parameters and interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 levels in saliva from totally edentulous patients with peri-implant disease. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2006, 21, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, H.R.; Sharifi, R.; Mirbahari, S.; Montazerian, S.; Sadeghi, M.; Rostami, S. A systematic review and meta-analysis study of salivary and serum interleukin-8 levels in oral lichen planus. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2018, 35, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoreishian, F.S.; Tavangar, A.; Ghalayani, P.; Boroujeni, M.A. Salivary levels of interleukin-8 in oral lichen planus and diabetic patients: A biochemical study. Dent. Res. J. 2017, 14, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, A.; Wang, J.; Chia, J.-S.; Chiang, C.-P. Serum interleukin-8 level is a more sensitive marker than serum interleukin-6 level in monitoring the disease activity of oral lichen planus. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 152, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.J.P.O.; Junior, M.M.; Lourenço, E.J.V.; Teles, D.D.M.; Figueredo, C.M.S. Cytokines expression in saliva and peri-implant crevicular fluid of patients with peri-implant disease. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 25, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.S.; Mosconi, C.; Jaeger, F.; Wastowski, I.; Aguiar, M.C.F.; Silva, T.A.; Ribeiro-Rotta, R.; Costa, N.L.; Batista, A.C. Overexpression of immunomodulatory mediators in oral precancerous lesions. Hum. Immunol. 2017, 78, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchettini, A.; Finamore, F.; Puxeddu, I.; Ferro, F.; Baldini, C. Salivary extracellular vesicles versus whole saliva: New perspectives for the identification of proteomic biomarkers in Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. 118), 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Liu, S.; Xu, H.; Ji, N.; Zhou, M.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; et al. Interleukin-37 expression and its potential role in oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tobón-Arroyave, S.I.; Isaza-Guzman, D.M.; Restrepo-Cadavid, E.M.; Zapata-Molina, S.M.; Martínez-Pabón, M.C. Association of salivary levels of the bone remodelling regulators sRANKL and OPG with periodontal clinical status. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buduneli, N.; Kinane, D.F. Host-derived diagnostic markers related to soft tissue destruction and bone degradation in periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabbagh, M.; Alladah, A.; Lin, Y.; Kryscio, R.J.; Thomas, M.V.; Ebersole, J.L.; Miller, C.S. Bone remodeling-associated salivary biomarker MIP-1α distinguishes periodontal disease from health. J. Periodontal Res. 2011, 47, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, D.H.; Markowitz, K.; Furgang, D.; Fairlie, K.; Ferrandiz, J.; Nasri, C.; McKiernan, M.; Donnelly, R.; Gunsolley, J. Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1α: A Salivary Biomarker of Bone Loss in a Longitudinal Cohort Study of Children at Risk for Aggressive Periodontal Disease? J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miricescu, D.; Totan, A.; Calenic, B.; Mocanu, B.; Didilescu, A.; Mohora, M.; Spinu, T.; Greabu, M. Salivary biomarkers: Relationship between oxidative stress and alveolar bone loss in chronic periodontitis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2013, 72, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappacosta, B.; Manni, A.; Persichilli, S.; Boari, A.; Scribano, D.; Minucci, A.; Raffaelli, L.; Giardina, B.; De Sole, P. Salivary thiols and enzyme markers of cell damage in periodontal disease. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugahara, T.; Shosenji, Y.; Ohashi, K. Screening for periodontitis in pregnant women with salivary enzymes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2007, 34, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, R.; Khan, S.N.; Iqbal, P.S.; Soman, R.R.; Chakkarayan, J.; Krishnan, V. Estimation of Specific Salivary Enzymatic Biomarkers in Individuals with Gingivitis and Chronic Periodontitis: A Clinical and Biochemical Study. J. Int. Oral Health 2015, 7, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dabra, S.; China, K.; Kaushik, A. Salivary enzymes as diagnostic markers for detection of gingival/periodontal disease and their correlation with the severity of the disease. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2012, 16, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Tamaki, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Arakawa, H.; Tsurumoto, A.; Kirimura, K.; Sato, T.; Hanada, N.; Kamoi, K. Screening of periodontitis with salivary enzyme tests. J. Oral Sci. 2006, 48, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gürsoy, U.K.; Könönen, E.; Pradhan-Palikhe, P.; Tervahartiala, T.; Pussinen, P.; Suominen-Taipale, L.; Sorsa, T. Salivary MMP-8, TIMP-1, and ICTP as markers of advanced periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira-Junior, R.; Öztürk, V.Ö.; Emingil, G.; Bostanci, N.; Boström, E.A. Salivary and Serum Markers Related to Innate Immunity in Generalized Aggressive Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2017, 88, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thumbigere-Math, V.; Michalowicz, B.S.; De Jong, E.P.; Griffin, T.J.; Basi, D.L.; Hughes, P.J.; Tsai, M.L.; Swenson, K.K.; Rockwell, L.; Gopalakrishnan, R. Salivary proteomics in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Dis. 2013, 21, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thumbigere-Math, V.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Hughes, P.J.; Basi, D.L.; Tsai, M.L.; Swenson, K.K.; Rockwell, L.; Gopalakrishnan, R. Serum Markers of Bone Turnover and Angiogenesis in Patients with Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw after Discontinuation of Long-Term Intravenous Bisphosphonate Therapy. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 74, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isaza-Guzman, D.M.; Arias-Osorio, C.; Martínez-Pabón, M.C.; Tobón-Arroyave, S.I. Salivary levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1: A pilot study about the relationship with periodontal status and MMP-9−1562C/T gene promoter polymorphism. Arch. Oral Boil. 2011, 56, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrakshi, C.; Srinivas, N.; Mehta, D.S. A comparative evaluation of hepatocyte growth factor levels in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva and its correlation with clinical parameters in patients with and without chronic periodontitis: A clinico-biochemical study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2011, 15, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilczyńska-Borawska, M.; Borawski, J.; Baginska, J.; Małyszko, J.; Myśliwiec, M. Hepatocyte Growth Factor in Saliva of Patients with Renal Failure and Periodontal Disease. Ren. Fail. 2012, 34, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyńska-Borawska, M.; Borawski, J.; Kovalchuk, O.; Chyczewski, L.; Stokowska, W. Hepatocyte growth factor in saliva is a potential marker of symptomatic periodontal disease. J. Oral Sci. 2006, 48, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aqrawi, L.A.; Galtung, H.K.; Guerreiro, E.M.; Øvstebø, R.; Thiede, B.; Utheim, T.P.; Chen, X.; Utheim Øygunn, A.; Palm, Ø.; Skarstein, K.; et al. Proteomic and histopathological characterisation of sicca subjects and primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients reveals promising tear, saliva and extracellular vesicle disease biomarkers. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garza-García, F.; Delgado-García, G.; Garza-Elizondo, M.; Ceceñas-Falcón, L.Á.; Galarza-Delgado, D.; Riega-Torres, J. Salivary β2-microglobulin positively correlates with ESSPRI in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rev. Bras. Reum. Engl. Ed. 2017, 57, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Xi, G.; Maile, L.A.; Wai, C.; Rosen, C.J.; Clemmons, D.R. Insulin-Like Growth Factor (IGF) Binding Protein 2 Functions Coordinately with Receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase β and the IGF-I Receptor to Regulate IGF-I-Stimulated Signaling. Mol. Cell. Boil. 2012, 32, 4116–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suresh, L.; Malyavantham, K.S.; Shen, L.; Ambrus, J.L. Investigation of novel autoantibodies in Sjogren’s syndrome utilizing Sera from the Sjogren’s international collaborative clinical alliance cohort. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, S.; Metgud, R. Estimation of salivary lactate dehydrogenase in oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A biochemical study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.R.; Chadha, R.; Babu, S.; Kumari, S.; Bhat, S.; Achalli, S. Salivary lactate dehydrogenase levels in oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A biochemical and clinicopathological study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2012, 8, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, F.; Assunção, A.C.; Caldeira, P.C.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Bernardes, V.F.; Aguiar, M.C.F. Is salivary epidermal growth factor a biomarker for oral leukoplakia? A preliminary study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 119, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffmann, R.R.; Yurgel, L.S.; Campos, M.M. Evaluation of salivary endothelin-1 levels in oral squamous cell carcinoma and oral leukoplakia. Regul. Pept. 2011, 166, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.Á.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; González-Ruiz, I.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Lenouvel, D.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; Ramos-García, P. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.Á.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; González-Ruíz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Ramos-García, P. Malignant transformation risk of oral lichen planus: A systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019, 96, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurago, Z. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: An overview. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2016, 122, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-López, E.; Santos-Ruiz, A.; Gonzalez, R.; Navarrete-Navarrete, N.; Ortego-Centeno, N.; Martínez-Augustín, O.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, M.; Peralta-Ramírez, M.I. Analyses of hair and salivary cortisol for evaluating hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activation in patients with autoimmune disease. Stress 2017, 20, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Upadhyay, R.B.; Carnelio, S.; Shenoy, R.; Gyawali, P.; Mukherjee, M. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid reaction. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2010, 70, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezer, E.; Ozugurlu, F.; Ozyurt, H.; Sahin, S.; Etikan, I. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in lichen planus. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 32, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugermann, P.B.; Savage, N.W.; Seymour, G.; Walsh, L.J. Is there a role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in oral lichen planus? J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1996, 25, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, T. IL-6: From its discovery to clinical applications. Int. Immunol. 2010, 22, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, C.; Zhu, M.; Song, C.; Li, C.; Du, G.; Deng, Y.; Nie, H.; et al. Enhanced T-cell proliferation and IL-6 secretion mediated by overexpression of TRIM21 in oral lesions of patients with oral lichen planus. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2019, 49, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slots, J. Periodontitis: Facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontology 2000 2017, 75, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, R.C. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 1991, 26, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkedal-Hansen, H. Role of cytokines and inflammatory mediators in tissue destruction. J. Periodontal Res. 1993, 28, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, A.; Gigante, I.; Colucci, S.; Grano, M. Periodontal Disease: Linking the Primary Inflammation to Bone Loss. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fox, I.R.; Kang, I. Pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1992, 18, 517–538. [Google Scholar]

- Tincani, A.; Andreoli, L.; Cavazzana, I.; Doria, A.; Favero, M.; Fenini, M.-G.; Franceschini, F.; Lojacono, A.; Nascimbeni, G.; Santoro, A.; et al. Novel aspects of Sjögren’s syndrome in 2012. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venables, P.J. Sjögren’s syndrome. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2004, 18, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavragani, C.P. Mechanisms and New Strategies for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Annu. Rev. Med. 2017, 68, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márton, K.D.; Boros, I.; Varga, G.; Zelles, T.; Fejérdy, P.; Zeher, M.; Nagy, G. Evaluation of palatal saliva flow rate and oral manifestations in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Oral Dis. 2006, 12, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali, C.; Bombardieri, S.; Jonsson, R.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Alexander, E.L.E.; Carsons, S.E.; Daniels, T.; Fox, P.C.I.; Fox, R.; Kassan, S.S.; et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: A revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiboski, S.C.; Shiboski, C.H.; Criswell, L.A.; Baer, A.N.; Challacombe, S.; Lanfranchi, H.; Schiodt, M.; Umehara, H.; Vivino, F.; Zhao, Y.; et al. American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: A data-driven, expert consensus approach in the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.A.; Criswell, L.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 76, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naushin, T.; Khan, M.M.; Ahmed, S.; Hassan, M.-U.; Iqbal, F.; Bashir, N.; Khan, A.S. Determination of Ki-67 expression in oral leukoplakia in snuff users and non-users in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Prof. Med. J. 2020, 27, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehta, T.; Shah, S.; Dave, B.; Shah, R.; Dave, R. Socioeconomic and cultural impact of tobacco in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujatha, D.; Hebbar, P.B.; Pai, A. Prevalence and correlation of oral lesions among tobacco smokers, tobacco chewers, areca nut and alcohol users. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 1633–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gupta, V.; Abhisheik, K.; Balasundari, S.; Devendra, N.K.; Shadab, K.; Anupama, M. Identification of Candida albicans using different culture media and its association in leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Yamaura, C.; Ohara-Nemoto, Y.; Tajika, S.; Kodama, Y.; Ohya, T.; Harada, R.; Kimura, S. Streptococcus anginosus infection in oral cancer and its infection route. Oral Dis. 2005, 11, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanowska-Dygdała, M.; Duś, I.; Radwan-Oczko, M. The presence of Helicobacter pylori in oral cavities of patients with leukoplakia and oral lichen planus. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2016, 24, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De La Cour, C.D.; Sperling, C.D.; Belmonte, F.; Syrjänen, S.; Kjaer, S.K. Human papillomavirus prevalence in oral potentially malignant disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidry, J.T.; Birdwell, C.E.; Scott, R.S. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of oral cancers. Oral Dis. 2017, 24, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushlinskiĭ, E.; Nagibin, A.A.; Laptev, I.P. Determination of the sensitivity of tumorous and pretumorous processes in the oral mucosa to steroid hormones. Stomatology 1988, 67, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan, G.; Ramani, P.; Patankar, S.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Analysis of estrogen metabolites in oral Leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Pharm. Bio Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, F.W.; Miguel, A.F.P.; Dutra-Horstmann, K.L.; Porporatti, A.L.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Guerra, E.N.S.; Rivero, E.R.C. Prevalence of oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Ariyawardana, A. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia: A systematic review of observational studies. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 45, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Waal, I. Oral leukoplakia: A diagnostic challenge for clinicians and pathologists. Oral Dis. 2018, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jung, R.E.; Zembic, A.; Pjetursson, B.E.; Zwahlen, M.; Thoma, D.S. Systematic review of the survival rate and the incidence of biological, technical, and aesthetic complications of single crowns on implants reported in longitudinal studies with a mean follow-up of 5 years. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khammissa, R.A.G.; Feller, L.; Meyerov, R.; Lemmer, J. Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: Clinical and histopathological characteristics and treatment. SADJ J. S. Afr. Dent. Assoc. = Tydskr. Suid-Afrik. Tandheelkd. Ver. 2012, 67, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, V. An Insight into Peri-Implantitis: A Systematic Literature Review. Prim. Dent. J. 2013, 2, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, R.; Henningsen, A.; Jung, O.; Heiland, M.; Hammächer, C.; Stein, J.M. Definition, etiology, prevention and treatment of peri-implantitis—A review. Head Face Med. 2014, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomes, A.M.; Douglas-De-Oliveira, D.W.; Costa, F.O. Could the biomarker levels in saliva help distinguish between healthy implants and implants with peri-implant disease? A systematic review. Arch. Oral Boil. 2018, 96, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokythas, A.; Karras, M.; Collins, E.; Flick, W.; Miloro, M.; Adami, G. Salivary Biomarkers Associated with Bone Deterioration in Patients with Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Fantasia, J.; Goodday, R.; Aghaloo, T.; Mehrotra, B.; O’Ryan, F. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw—2014 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1938–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; De Luna-Bertos, E.; Reyes-Botella, C.; Ruiz, C.; García-Martínez, O. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates modulate the antigenic profile and inhibit the maturation and biomineralization potential of osteoblast-like cells. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 19, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; De Luna-Bertos, E.; Ruiz, C.; García-Martínez, O. High doses of bisphosphonates reduce osteoblast-like cell proliferation by arresting the cell cycle and inducing apoptosis. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiba, T.; Mori, S.; Komatsubara, S.; Cao, Y.; Manabe, T.; Norimatsu, H.; Burr, D.B. The effects of suppressed bone remodeling by bisphosphonates on microdamage accumulation and degree of mineralization in the cortical bone of dog rib. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2005, 23, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landesberg, R.; Cozin, M.; Cremers, S.; Woo, V.; Kousteni, S.; Sinha, S.; Garrett-Sinha, L.A.; Raghavan, S. Inhibition of Oral Mucosal Cell Wound Healing by Bisphosphonates. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fedele, S.; Porter, S.; D’Aiuto, F.; Aljohani, S.; Vescovi, P.; Manfredi, M.; Arduino, P.G.; Broccoletti, R.; Musciotto, A.; Di Fede, O.; et al. Nonexposed Variant of Bisphosphonate-associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: A Case Series. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Ryan, F.; Khoury, S.; Liao, W.; Han, M.M.; Hui, R.L.; Baer, D.; Martin, D.; Donald, L.; Lo, J. Intravenous Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: Bone Scintigraphy as an Early Indicator. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsuoka, W.; Ueno, T.; Miyano, K.; Uezono, Y.; Enomoto, A.; Kaneko, M.; Ota, S.; Soga, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Ushijima, T. Metabolomic profiling reveals salivary hypotaurine as a potential early detection marker for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagan, J.; Jiménez-Soriano, Y.; Gomez, D.; Sirera, R.; Poveda, R.; Scully, C. Collagen telopeptide (serum CTX) and its relationship with the size and number of lesions in osteonecrosis of the jaws in cancer patients on intravenous bisphosphonates. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 1088–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prá, K.J.D.; Lemos, C.; Okamoto, R.; Soubhia, A.; Pellizzer, E. Efficacy of the C-terminal telopeptide test in predicting the development of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.W.; Kong, K.A.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, S.K.; Cha, I.H.; Kim, M.-R. Prospective biomarker evaluation in patients with osteonecrosis of the jaw who received bisphosphonates. Bone 2013, 57, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Biomarker | Oral Pathology | Salivary Levels in Diagnosed Patients | Clinical Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | OLP | Increased levels [17,18,19] | Diagnosis and recurrence of the pathology [20,21] | |

| Nitric Oxide | OLP | Increased levels [19] | Prognosis and presence of ulcers [22,23] | |

| ROS | OLP | Unaltered levels [22] | Cellular oxidative stress [22,24] | |

| CRP | OLP | Increased levels [22,25,26] | OLP progression [26] | |

| PD | Increased levels [27,28,29,30] | PD prognosis (modulation of the inflammation) [27,28,29,30] | ||

| TNF- α | OLP | Increased levels [19,31,32,33] | OLP diagnosis, commencement and progression [19,31] | |

| PD | Increased levels [34] Decreased levels [35] | Uncertain diagnosis, and prognosis role [36,37,38,39] | ||

| OL | Increased levels [40,41,42] Unaltered levels [43,44] | OL prognosis (malignant transformation, pre-oral cancer, and precancerous marker) [40,41,42] | ||

| PI | Increased levels [45] | Diagnosis of the pathology [45] | ||

| IL1 | IL1β | PD | Increased levels [35,38,39,46,47,48,49,50] | Diagnosis and progression (inflammatory modulation, severity-bone resorption, generalized PD and PD severity) [51,52,53,54,55] |

| OL | Unaltered levels [44] | - | ||

| PI | Increased levels [45,56] | Diagnosis of the pathology [45,56] | ||

| IL1α & IL1β | OLP | Increased levels [19,32] | Immune and inflammatory response modulator [57,58] | |

| MRONJ | Increased levels [59,60] | MRONJ diagnosis [59,60] | ||

| IL1RA | MRONJ | Increased levels [59,60] | MRONJ diagnosis [59,60] | |

| IL4 | OLP | Increased levels [19,61] | IL4 is not a good salivary marker for OLP prognosis [32,62] | |

| PD | Increased levels [63] | - | ||

| IL6 | OLP | Increased levels [19,32,64,65] | OLP prognosis (severity and wound marker). IL6 salivary marker is a good option for monitoring the treatment response [32,66] | |

| PD | Increased levels [38,63,67] Unaltered levels [27,39,49,68] | PD prognosis (inflammatory modulator) [37,69,70] | ||

| OL | Increased levels [41,71,72,73] Unaltered levels [44] | OL prognosis (tumor growth and higher blood vessel density) [74] | ||

| PI | Increased levels [45,75] | Early diagnosis and prognostic value [45,75] | ||

| MRONJ | Increased levels [59,60] | MRONJ diagnosis [59,60] | ||

| IL8 | OLP | Increased Levels [19,76,77] | IL8 is a solid salivary biomarker for OLP severity [32,66,78] | |

| OL | Increased levels [41,71,72,73] Unaltered levels [44] | OL prognosis (tumor growth and higher blood vessel density) [74] | ||

| PI | Increased Levels [79] | PI diagnosis [79] | ||

| IL10 | OL | Increased Levels [42,80] Unaltered levels [44] | Uncertain association with premalignant oral lesions [42,80] | |

| PI | Increased levels [45,75] | Early diagnosis and prognostic value [45,75] | ||

| IL12 | pSS | Increased Levels [81] | Diagnostic and prognostic value [81] | |

| IL17 | PD | Increased levels [54,63] | Localized periodontitis [54] | |

| IL23 | PD | Increased levels [54] | Localized periodontitis [54] | |

| IL37 | OL | Increased Levels [82] | ||

| RANKL | PD | Increased levels [83] Unaltered levels [34,84] | Uncertain prognosis value (bone loss) [34,83,84] | |

| MIP-1 | PD | Increased levels [85,86] | Diagnosis [85,86] | |

| OPG | PD | Decreased levels [83] Unaltered levels [34,84] | Uncertain prognosis value (bone loss) [34,83,84] | |

| OSC | PD | Decreased levels [83] Unaltered levels [34,84] | Uncertain prognosis value (bone loss) [34,83,84] | |

| ALP | PD | Increased levels [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | Diagnosis of the pathology [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | |

| LDH | PD | Increased levels [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | Diagnosis of the pathology [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | |

| AST | PD | Increased levels [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | Diagnosis of the pathology [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | |

| ALT | PD | Increased levels [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | Diagnosis of the pathology [67,87,88,89,90,91,92] | |

| MMP8 | PD | Increased levels [27,39,47,48,67,87,93] | Very useful salivary biomarker for the diagnosis of PD [27,39,47,48,67,87,93] and PD severity [94] | |

| MMP9 | PD | Increased levels [27,35] | Diagnosis [27,35] | |

| MRONJ | Increased levels [95,96] | MRONJ diagnosis [95,96] | ||

| TIMP1 | PD | Decreased levels [93,97] | PD prognosis (advanced PD) [93] | |

| HGF | PD | Increased levels [98,99] | Prognosis of the pathology [98,99,100] | |

| NLRP3 | PD | Increased levels [55] | PD severity and chronicity. Also useful as a salivary biomarker for preventive or therapeutic purposes [55] | |

| CD44 | pSS | Increased levels [101] | Diagnostic and prognostic value [101] | |

| B2M | pSS | Increased levels [102] | Diagnostic and prognostic value [102] | |

| SP1 | pSS | Increased levels [103,104] | Early diagnosis and prognostic value [103,104] | |

| PSP | pSS | Increased levels [103,104] | Early diagnosis and prognostic value [103,104] | |

| CA6 | pSS | Increased levels [103,104] | Early diagnosis and prognostic value [103,104] | |

| LDH | OL | Increased levels [105,106] | Risk of malignant transformation of OL [105,106] | |

| TGFβ | OL | Unaltered levels [80,107,108] | Uncertain diagnosis and prognosis value [80,107,108] | |

| EGF | OL | Unaltered levels [80,107,108] | Uncertain diagnosis and prognosis value [80,107,108] | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; Costela-Ruiz, V.J.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Ruiz, C.; Illescas-Montes, R. Salivary Biomarkers and Their Application in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of the Most Common Oral Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21145173

Melguizo-Rodríguez L, Costela-Ruiz VJ, Manzano-Moreno FJ, Ruiz C, Illescas-Montes R. Salivary Biomarkers and Their Application in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of the Most Common Oral Pathologies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(14):5173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21145173

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelguizo-Rodríguez, Lucía, Victor J. Costela-Ruiz, Francisco Javier Manzano-Moreno, Concepción Ruiz, and Rebeca Illescas-Montes. 2020. "Salivary Biomarkers and Their Application in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of the Most Common Oral Pathologies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 14: 5173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21145173