PDZ-Containing Proteins Targeted by the ACE2 Receptor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Peptide Synthesis

2.2. Holdup Assay

2.3. Conversion of BI Values to Dissociation Equilibrium Constants

3. Results

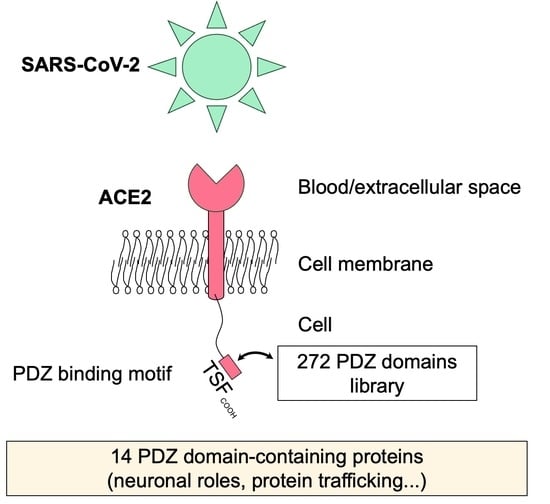

3.1. The ACE2 PDZ-Binding Motif Recognizes 14 PDZ Domains with Affinity Values of Interactions Ranging from 3 μM to 81 μM

3.2. The PDZ-Binding Motif of ACE2 Targets Proteins Involved in Protein Trafficking and Some Proteins Preferentially Expressed in Neurons

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K.-Y.; et al. Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppisetti, R.K.; Fulcher, Y.G.; Van Doren, S.R. Fusion Peptide of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Rearranges into a Wedge Inserted in Bilayered Micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13205–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An Overview of Their Replication and Pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vianello, A.; Del Turco, S.; Babboni, S.; Silvestrini, B.; Ragusa, R.; Caselli, C.; Melani, L.; Fanucci, L.; Basta, G. The Fight against COVID-19 on the Multi-Protease Front and Surroundings: Could an Early Therapeutic Approach with Repositioning Drugs Prevent the Disease Severity? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V’kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus Biology and Replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.-Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.-S. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Cell Receptor Gene ACE2 in a Wide Variety of Human Tissues. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukassen, S.; Chua, R.L.; Trefzer, T.; Kahn, N.C.; Schneider, M.A.; Muley, T.; Winter, H.; Meister, M.; Veith, C.; Boots, A.W.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 Are Primarily Expressed in Bronchial Transient Secretory Cells. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mészáros, B.; Sámano-Sánchez, H.; Alvarado-Valverde, J.; Čalyševa, J.; Martínez-Pérez, E.; Alves, R.; Shields, D.C.; Kumar, M.; Rippmann, F.; Chemes, L.B.; et al. Short Linear Motif Candidates in the Cell Entry System Used by SARS-CoV-2 and Their Potential Therapeutic Implications. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliche, J.; Kuss, H.; Ali, M.; Ivarsson, Y. Cytoplasmic Short Linear Motifs in ACE2 and Integrin Β3 Link SARS-CoV-2 Host Cell Receptors to Mediators of Endocytosis and Autophagy. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gefter, J.; Sneddon, W.B.; Mamonova, T.; Friedman, P.A. ACE2 Interaction with Cytoplasmic PDZ Protein Enhances SARS-CoV-2 Invasion. iScience 2021, 24, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, K.; Charbonnier, S.; Travé, G. The Emerging Contribution of Sequence Context to the Specificity of Protein Interactions Mediated by PDZ Domains. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2648–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amacher, J.F.; Brooks, L.; Hampton, T.H.; Madden, D.R. Specificity in PDZ-Peptide Interaction Networks: Computational Analysis and Review. J. Struct. Biol. X 2020, 4, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincentelli, R.; Luck, K.; Poirson, J.; Polanowska, J.; Abdat, J.; Blémont, M.; Turchetto, J.; Iv, F.; Ricquier, K.; Straub, M.-L.; et al. Quantifying Domain-Ligand Affinities and Specificities by High-Throughput Holdup Assay. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caillet-Saguy, C.; Durbesson, F.; Rezelj, V.V.; Gogl, G.; Tran, Q.D.; Twizere, J.-C.; Vignuzzi, M.; Vincentelli, R.; Wolff, N. Host PDZ-Containing Proteins Targeted by SARS-CoV-2. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 5148–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhoo, Y.; Girault, V.; Turchetto, J.; Ramond, L.; Durbesson, F.; Fourquet, P.; Nominé, Y.; Cardoso, V.; Sequeira, A.F.; Brás, J.L.A.; et al. High-Throughput Production of a New Library of Human Single and Tandem PDZ Domains Allows Quantitative PDZ-Peptide Interaction Screening Through High-Throughput Holdup Assay. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2019, 2025, 439–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogl, G.; Jane, P.; Caillet-Saguy, C.; Kostmann, C.; Bich, G.; Cousido-Siah, A.; Nyitray, L.; Vincentelli, R.; Wolff, N.; Nomine, Y.; et al. Dual Specificity PDZ- and 14-3-3-Binding Motifs: A Structural and Interactomics Study. Struct. Lond. Engl. 1993 2020, 28, 747–759.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jané, P.; Gógl, G.; Kostmann, C.; Bich, G.; Girault, V.; Caillet-Saguy, C.; Eberling, P.; Vincentelli, R.; Wolff, N.; Travé, G.; et al. Interactomic Affinity Profiling by Holdup Assay: Acetylation and Distal Residues Impact the PDZome-Binding Specificity of PTEN Phosphatase. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, F.; Gallon, M.; Winfield, M.; Thomas, E.C.; Bell, A.J.; Heesom, K.J.; Tavaré, J.M.; Cullen, P.J. A Global Analysis of SNX27-Retromer Assembly and Cargo Specificity Reveals a Function in Glucose and Metal Ion Transport. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halff, E.F.; Szulc, B.R.; Lesept, F.; Kittler, J.T. SNX27-Mediated Recycling of Neuroligin-2 Regulates Inhibitory Signaling. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 2599–2607.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Badie, H.; Zhou, Y.; Mu, Y.; Loo, L.S.; Cai, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Yang, B.; et al. Loss of Sorting Nexin 27 Contributes to Excitatory Synaptic Dysfunction by Modulating Glutamate Receptor Recycling in Down’s Syndrome. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parente, D.J.; Morris, S.M.; McKinstry, R.C.; Brandt, T.; Gabau, E.; Ruiz, A.; Shinawi, M. Sorting Nexin 27 (SNX27) Variants Associated with Seizures, Developmental Delay, Behavioral Disturbance, and Subcortical Brain Abnormalities. Clin. Genet. 2020, 97, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, P.; Feng, G. SHANK Proteins: Roles at the Synapse and in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinman, E.J. New Functions for the NHERF Family of Proteins. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voltz, J.W.; Weinman, E.J.; Shenolikar, S. Expanding the Role of NHERF, a PDZ-Domain Containing Protein Adapter, to Growth Regulation. Oncogene 2001, 20, 6309–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shenolikar, S.; Weinman, E.J. NHERF: Targeting and Trafficking Membrane Proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2001, 280, F389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, P.; Quraishe, S.; French, P.; O’Connor, V. Expression of the MAST Family of Serine/Threonine Kinases. Brain Res. 2008, 1195, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, R.; Leca, I.; van Dijk, T.; Weiss, J.; van Bon, B.W.; Sergaki, M.C.; Gstrein, T.; Breuss, M.; Tian, G.; Bahi-Buisson, N.; et al. Mutations in MAST1 Cause Mega-Corpus-Callosum Syndrome with Cerebellar Hypoplasia and Cortical Malformations. Neuron 2018, 100, 1354–1368.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrien, E.; Chaffotte, A.; Lafage, M.; Khan, Z.; Préhaud, C.; Cordier, F.; Simenel, C.; Delepierre, M.; Buc, H.; Lafon, M.; et al. Interference with the PTEN-MAST2 Interaction by a Viral Protein Leads to Cellular Relocalization of PTEN. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foy, B.H.; Carlson, J.C.T.; Reinertsen, E.; Padros I Valls, R.; Pallares Lopez, R.; Palanques-Tost, E.; Mow, C.; Westover, M.B.; Aguirre, A.D.; Higgins, J.M. Association of Red Blood Cell Distribution Width with Mortality Risk in Hospitalized Adults with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2022058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, E.; Christensen, K.R.; Bryant, E.; Schneider, A.; Rakotomamonjy, J.; Muir, A.M.; Giannelli, J.; Littlejohn, R.O.; Roeder, E.R.; Schmidt, B.; et al. Pathogenic MAST3 Variants in the STK Domain Are Associated with Epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 90, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whited, J.L.; Robichaux, M.B.; Yang, J.C.; Garrity, P.A. Ptpmeg Is Required for the Proper Establishment and Maintenance of Axon Projections in the Central Brain of Drosophila. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2007, 134, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hendriks, W.J.A.J.; Böhmer, F.-D. Non-Transmembrane PTPs in Cancer. In Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in Cancer; Neel, B.G., Tonks, N.K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4939-3649-6. [Google Scholar]

- Khazaei, M.R.; Püschel, A.W. Phosphorylation of the Par Polarity Complex Protein Par3 at Serine 962 Is Mediated by Aurora a and Regulates Its Function in Neuronal Polarity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33571–33579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; An, Y.; Gao, Y.; Guo, L.; Rui, L.; Xie, H.; Sun, M.; Lam Hung, S.; Sheng, X.; Zou, J.; et al. Rare Deleterious PARD3 Variants in the APKC-Binding Region Are Implicated in the Pathogenesis of Human Cranial Neural Tube Defects Via Disrupting Apical Tight Junction Formation. Hum. Mutat. 2017, 38, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farber, M.J.; Rizaldy, R.; Hildebrand, J.D. Shroom2 Regulates Contractility to Control Endothelial Morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Ramsakha, N.; Sharma, R.; Gulia, R.; Ojha, P.; Lu, W.; Bhattacharyya, S. The Post-Synaptic Scaffolding Protein Tamalin Regulates Ligand-Mediated Trafficking of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 8575–8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doobay, M.F.; Talman, L.S.; Obr, T.D.; Tian, X.; Davisson, R.L.; Lazartigues, E. Differential Expression of Neuronal ACE2 in Transgenic Mice with Overexpression of the Brain Renin-Angiotensin System. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 292, R373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pacheco-Herrero, M.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Harrington, C.R.; Flores-Martinez, Y.M.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; León-Aguilar, A.M.; Martínez-Gómez, P.A.; Campa-Córdoba, B.B.; Apátiga-Pérez, R.; Corniel-Taveras, C.N.; et al. Elucidating the Neuropathologic Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 660087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, B.E.L.; Melero, C.; Temkin, P.; Lei, C.; Hong, W.; Kortemme, T.; von Zastrow, M. SNX27 Mediates PDZ-Directed Sorting from Endosomes to the Plasma Membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Feng, F.; Hu, G.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, W.; Cai, X.; Sun, Z.; Han, W.; et al. A Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen Identifies Host Factors That Regulate SARS-CoV-2 Entry. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhong, K.; Zhao, J.; Yong, X.; Tong, A.; Jia, D. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Harnesses SNX27-mediated Endocytic Recycling Pathway. MedComm 2021, mco2.92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleem, J.; Dirksen, W.P.; Martinez, M.P.; Shkriabai, N.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; Ratner, L.; Green, P.L. HTLV-1 Tax-1 Interacts with SNX27 to Regulate Cellular Localization of the HTLV-1 Receptor Molecule, GLUT1. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganti, K.; Massimi, P.; Manzo-Merino, J.; Tomaić, V.; Pim, D.; Playford, M.P.; Lizano, M.; Roberts, S.; Kranjec, C.; Doorbar, J.; et al. Interaction of the Human Papillomavirus E6 Oncoprotein with Sorting Nexin 27 Modulates Endocytic Cargo Transport Pathways. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Javier, R.T.; Rice, A.P. Emerging Theme: Cellular PDZ Proteins as Common Targets of Pathogenic Viruses. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 11544–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jia, H.P.; Look, D.C.; Shi, L.; Hickey, M.; Pewe, L.; Netland, J.; Farzan, M.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.; Perlman, S.; McCray, P.B. ACE2 Receptor Expression and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection Depend on Differentiation of Human Airway Epithelia. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14614–14621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, Z.; Terrien, E.; Delhommel, F.; Lefebvre-Omar, C.; Bohl, D.; Vitry, S.; Bernard, C.; Ramirez, J.; Chaffotte, A.; Ricquier, K.; et al. Structure-Based Optimization of a PDZ-Binding Motif within a Viral Peptide Stimulates Neurite Outgrowth. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 13755–13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraud, E.; Del Val, C.O.; Caillet-Saguy, C.; Zehrouni, N.; Khou, C.; Caillet, J.; Jacob, Y.; Pardigon, N.; Wolff, N. Role of PDZ-Binding Motif from West Nile Virus NS5 Protein on Viral Replication. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Lazartigues, E. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 in the Brain: Properties and Future Directions. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alenina, N.; Bader, M. ACE2 in Brain Physiology and Pathophysiology: Evidence from Transgenic Animal Models. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Zhang, C.; Israelow, B.; Lu-Culligan, A.; Prado, A.V.; Skriabine, S.; Lu, P.; Weizman, O.-E.; Liu, F.; Dai, Y.; et al. Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in Human and Mouse Brain. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20202135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, A.B.; Engin, E.D.; Engin, A. Current Opinion in Neurological Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 25, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menni, C.; Valdes, A.M.; Freidin, M.B.; Sudre, C.H.; Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Ganesh, S.; Varsavsky, T.; Cardoso, M.J.; El-Sayed Moustafa, J.S.; et al. Real-Time Tracking of Self-Reported Symptoms to Predict Potential COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Melo, G.D.; Lazarini, F.; Levallois, S.; Hautefort, C.; Michel, V.; Larrous, F.; Verillaud, B.; Aparicio, C.; Wagner, S.; Gheusi, G.; et al. COVID-19-Associated Olfactory Dysfunction Reveals SARS-CoV-2 Neuroinvasion and Persistence in the Olfactory System. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojkova, D.; Klann, K.; Koch, B.; Widera, M.; Krause, D.; Ciesek, S.; Cinatl, J.; Münch, C. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-Infected Host Cells Reveals Therapy Targets. Nature 2020, 583, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caillet-Saguy, C.; Wolff, N. PDZ-Containing Proteins Targeted by the ACE2 Receptor. Viruses 2021, 13, 2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13112281

Caillet-Saguy C, Wolff N. PDZ-Containing Proteins Targeted by the ACE2 Receptor. Viruses. 2021; 13(11):2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13112281

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaillet-Saguy, Célia, and Nicolas Wolff. 2021. "PDZ-Containing Proteins Targeted by the ACE2 Receptor" Viruses 13, no. 11: 2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13112281