Published online Oct 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i39.8844

Peer-review started: November 4, 2015

First decision: December 11, 2015

Revised: January 5, 2016

Accepted: March 18, 2016

Article in press: March 18, 2016

Published online: October 21, 2016

Cyclophosphamide is a potent cytotoxic agent used in many clinical settings. The main risks of cyclophosphamide therapy include hematological disorders, infertility, hemorrhagic cystitis and malignancies. Gastrointestinal side effects reported to date are often non-specific and not severe. We present the first case of a fatal small bowel enteritis and pan-colitis which appears to be associated with cyclophosphamide. We aim to raise the readers’ awareness of this significant adverse event to facilitate clinical suspicion and early recognition in potential future cases.

Core tip: The well-known adverse effects associated with cyclophosphamide include bone marrow suppression, hemorrhagic cystitis and malignancies. This case report describes the first case of fatal and irreversible small bowel enteritis and pan-colitis associated with cyclophosphamide.

- Citation: Yang LS, Cameron K, Papaluca T, Basnayake C, Jackett L, McKelvie P, Goodman D, Demediuk B, Bell SJ, Thompson AJ. Cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis: A rare association with severe enteritis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(39): 8844-8848

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i39/8844.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i39.8844

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent with cytotoxic and immunosuppressive properties. It is frequently used to treat a variety of inflammatory and malignant conditions, either as a sole agent or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs or glucocorticoids. Toxicities associated with cyclophosphamide are well-described. Significant adverse effects include dose-related leukopenia, hemorrhagic cystitis, infertility, secondary malignancies and pulmonary toxicity[1]. Reported gastrointestinal side effects include dose-related nausea, stomatitis and a single case of hemorrhagic colitis. In this report, we describe the case of a male patient with fatal small bowel enteritis and pan-colitis which was associated with four weeks of cyclophosphamide therapy.

A 60-year-old male was diagnosed with histologically confirmed glomerulonephritis secondary to anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody -positive microscopic polyangiitis, following investigations for elevated creatinine on routine blood test. He was treated in hospital with intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg daily) and oral cyclophosphamide (100 mg daily) for three days. He was discharged home on a weaning course of prednisolone and cyclophosphamide, with normalisation of his renal function.

Two weeks following this admission, the patient was admitted to a regional hospital with a two day history of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea with intolerance of oral intake. His wife had had similar symptoms recently. The patient developed large volume watery diarrhea, up to eight liters per day. He required transfer to a tertiary hospital intensive care unit where he received hemofiltration for hypovolemic acute kidney injury. Cyclophosphamide was initially reduced to 50 mg daily and then ceased in setting of potential infectious pathology. The patient had received approximately one month of cyclophosphamide, up to 2.1 g of total dose. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was commenced including tazobactam and piperacillin, intravenous metronidazole and ganciclovir. His stool specimen showed secretory diarrhoea with no infective agents identified. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and chromogranin levels were also non-diagnostic.

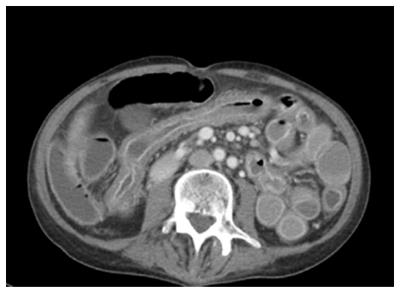

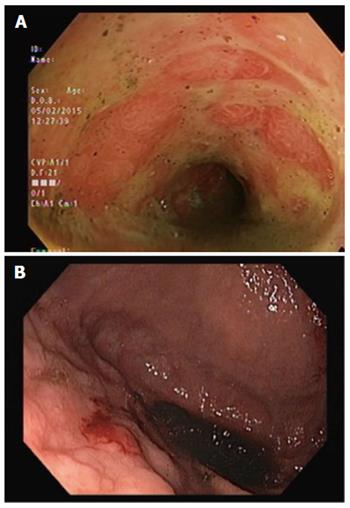

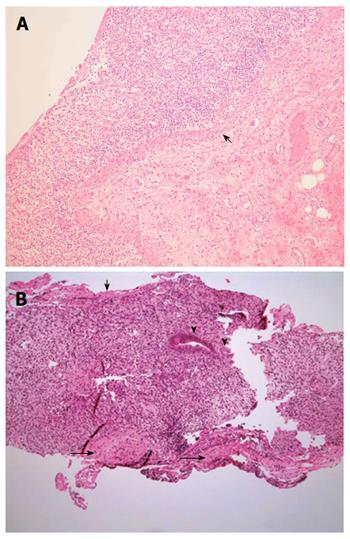

Serial computed tomographs of his abdomen revealed diffuse mural thickening of the small and large bowel. Upper and lower endoscopic evaluations demonstrated denuded and erythematous mucosa in the duodenum, as well as from sigmoid colon to terminal ileum with no significant interval change in macroscopic appearance (Figure 1). The rectum was relatively spared. Histopathology showed full thickness mucosal ulceration and inflammation throughout the terminal ileum and large bowel (Figure 2). There were no features of inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis or viral inclusions.

His diarrhea persisted up to six liters daily despite empirical treatment with maximal doses of antidiarrheals, octreotide and cholestyramine. Repeat imaging, stool specimens, endoscopic evaluation and histopathology failed to reveal an infectious, neuroendocrine, inflammatory or neoplastic etiology. Repeat colonic biopsies showed regenerative mucosal changes. In particular, viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bacterial and fungal cultures were negative on repeated testing. He required continuous intravenous therapy, electrolyte replacements and total parenteral nutrition for severe hypoalbuminemia. Infliximab was administered as empirical therapy without significant clinical or endoscopic improvement.

The patient subsequently developed septic complications with Enterobacter and Candida glabrata bacteremia. He returned to intensive care and subsequently died from severe acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Post-mortem examination showed multiple areas of hemorrhagic ulceration in the small bowel. Histology of the ulcerated areas in small bowel showed minimal residual mucosa. Similar changes, but less severe were seen in sections of ascending and transverse colon. A small amount of retained mucosa was seen in the descending colon with relative sparing of the rectum (Figure 3). No evidence of vasculitis or thromboemboli was seen in multiple sections of the bowel wall and mesentery. No definite infectious etiology was identified in histological sections (no bacteria or fungal organisms seen on PAS or Gram stains, immunohistochemistry for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus-1 and -2 were negative). Viral PCR from the small and large bowel tissue detected herpes simplex virus-1 DNA, but the clinical significance of this was uncertain in the absence of consistent immunohistochemistry and previously negative PCR.

Sections from all lobes of the lungs revealed changes of diffuse alveolar damage (shock lung) and metastatic pulmonary calcification. Culture detected Enterobacter faecium, Candida krusei and Pneumocystis jiroveci. Candida krusei was also cultured in small and large bowel.

We present a rare case of severe multifocal ulcerative enterocolitis affecting much of the small bowel and colon, which occurred in close temporal relation to cyclophosphamide. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of cyclophosphamide-associated enterocolitis in literature. It is a rare but serious adverse event that clinicians should consider in setting of cyclophosphamide.

Severe gastrointestinal toxicity is not commonly associated with cyclophosphamide and data on the association between cyclophosphamide and enteropathy are scarce. There is a single case report of hemorrhagic colitis following cyclophosphamide treatment of polymyositis[2]. The findings of this case report were similar to our case, but confined to the colon. In that report, endoscopic and histologic examination revealed nonspecific colitis with ulcerations, which resolved after cessation of cyclophosphamide and hydrocortisone rectal enemas. Other available literature mainly describes the therapeutic use of pulse cyclophosphamide in gastrointestinal vasculitis and refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Although not commonly utilized, monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide has been shown to be safe and efficacious in induction and maintenance of remission in severe steroid-refractory inflammatory bowel disease[3, 4]. Gastrointestinal vasculitis, as seen in polyarteritis nodosa, also responds to cyclophosphamide[5].

This case was a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to the unusual presentation and scarcity of similar case reports in literature. We considered the diagnosis of a severe neutropenic typhilitis secondary to cyclophosphamide. Cyclophosphamide has been associated with neutropenic enterocolitis, which usually occurs within two weeks of chemotherapy[6]. However, it is associated with profound neutropenia on presentation and course of disease. Our patient did not demonstrate significant neutropenia even at nadir. Treatment for an auto-immune or vasculitic cause of enteritis with IV steroid and infliximab was unsuccessful. Tissue PCR and cultures for infective causes were negative ante-mortem but prolonged immunosuppression is associated with high risks of secondary infection. Whether this contributed to failure of mucosal regeneration in this case is unclear.

The pathophysiology of cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis is difficult to ascertain in this case. If the hemorrhagic enterocolitis was related to the cyclophosphamide, one postulated etiology would be extensive mucosal necrosis with such profound loss of the stem cell niches at the base of the crypts that no repopulation of the mucosal epithelium was possible. This does not seem likely as there was evidence of mucosal regeneration on repeat biopsies and at postmortem This would be the first case of this scenario occurring with cyclophosphamide, which is used widely for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease including patients with extensive ulceration and for patients with vasculitis of the gastrointestinal tract. It is not clear why this patient would have suffered such a severe insult with a total dose of only 2 grams. His course was complicated by acute hypovolaemic renal failure, metabolic acidosis and sepsis with Enterobacter and Candida septicemia.

Chemotherapy-related diarrhea is common and is often attributed to alimentary mucositis, which has a complex pathophysiology including alterations in the intestinal microbiome. Abrupt changes in the microbiome may result in excessive generation of reactive oxygen species in the epithelium, thereby upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines[7]. Changes in the microbial flora in this patient may have contributed to the ongoing enterocolitis even after cyclophosphamide was ceased.

The mechanisms of hemorrhagic cystitis due to cyclophosphamide have been shown to be specific to the bladder and attributed to urotoxicity of acrolein, a metabolite of the drug, and causing damage via multiple factors including tumor necrosis factor-alfa, interleukin-1-beta, cyclooxygenase-2, reactive oxygen and nitric oxide species, and PARP activation. This complication was not seen in our patient

Large volume fluid and electrolyte replacement and parenteral nutrition is required but volumes above three to four litres a day can only be sustained in inpatients, and intestinal transplantation may need consideration. Intestinal transplant was contraindicated in this case due to sepsis and malnutrition. Lastly, empiric treatment of viral and fungal infections seen in immunocompromised patients may be considered.

In conclusion, with this case report, we aim to highlight a potentially fatal and irreversible enteropathy associated with cyclophosphamide. The etiology, risk factors and treatment of this condition are not yet understood. However, early suspicion of this adverse event may facilitate timely cessation of the offending drug and provision of early supportive care and prophylactic antimicrobial therapy to prevent significant morbidity or mortality.

A 60-year-old man with glomerulonephritis presented with a 2-d history of severe watery diarrhoea and worsening renal function, 1 mo after oral cyclophosphamide therapy.

Severe enteritis and rectum-sparing pan-colitis, leading to acute renal injury, malabsorption and severe electrolyte disturbances, and ultimately fatal septic complications with Enterobacter and Candida glabrata bacteremia.

Infective colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis, neutropenic typhilitis, carcinoid syndrome, ischemic bowel.

Acute renal injury resolved with intravenous hydration and a short course of hemofiltration. Persistent hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia and hypoalbuminemia. Raised inflammatory markers, non-diagnostic vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and chromogranin levels. His stool specimen showed secretory diarrhoea with no infective agents cultured. On post-mortem biopsy, Enterobacter faecium, Candida krusei and Pneumocystis jiroveci were isolated in lungs and colon.

Computed tomography of the abdomen showed diffuse mural thickening of the small and large bowel.

Upper and lower endoscopy demonstrated denuded and erythematous mucosa in the duodenum, as well as from sigmoid colon to terminal ileum. Endoscopic biopsy of the small bowel and colon showed full thickness ulceration and granulation tissue with a few residual glands. There were no viral inclusions or granulomas.

Prophylactic antibiotics, antivirals and antifungals, anti-diarrhoeals, intravenous fluids and electrolytes, total parenteral nutrition, glucocorticoids and infliximab.

There is a single case report of hemorrhagic colitis following cyclophosphamide treatment of polymyositis. The findings of this case report were similar to our case, but confined to the colon. In that report, endoscopic and histologic examination revealed nonspecific colitis with ulcerations, which resolved after cessation of cyclophosphamide and hydrocortisone rectal enemas.

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating cytotoxic agent used in a variety of clinical settings as chemotherapeutic agent or immunosuppressant. Its main adverse effects include marrow suppression, infertility, hemorrhagic cystitis and malignancies. Gastrointestinal side effects rare and often non-specific and non-fatal.

This is a rare complication in association with cyclophosphamide therapy. Due to the unusual presentation and scarcity of similar case reports in literature, this case can be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Early suspicion and recognition of this adverse event may help prevent significant morbidity or mortality in potential future cases.

The report is well written. In case of any suspected case of colitis after administering cyclophosphamide, timely cessation of the offending drug should be advised to facilitate early, aggressive supportive care for the affected patient. Moreover, prophylactic antimicrobial therapy should be considered to prevent significant morbidity or mortality. This important message is to be disseminated to protect future adverse events during cyclophosphamide treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ingle SB, Krishnan T, Rostami K S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Fraiser LH, Kanekal S, Kehrer JP. Cyclophosphamide toxicity. Characterising and avoiding the problem. Drugs. 1991;42:781-795. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Bujakowska O, Kur-Zalewska J, Tłustochowicz W. Hemorrhagic colitis as a complication of treatment with cyclophosphamide. Reumatologica. 2011;49:275-278. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Barta Z, Tóth L, Zeher M. Pulse cyclophosphamide therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1278-1280. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rall JM, Mach SA, Dash PK. Intrahippocampal infusion of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor attenuates memory acquisition in rats. Brain Res. 2003;968:273-276. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Fauci AS, Katz P, Haynes BF, Wolff SM. Cyclophosphamide therapy of severe systemic necrotizing vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:235-238. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 403] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moran H, Yaniv I, Ashkenazi S, Schwartz M, Fisher S, Levy I. Risk factors for typhlitis in pediatric patients with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:630-634. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stringer AM, Al-Dasooqi N, Bowen JM, Tan TH, Radzuan M, Logan RM, Mayo B, Keefe DM, Gibson RJ. Biomarkers of chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea: a clinical study of intestinal microbiome alterations, inflammation and circulating matrix metalloproteinases. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1843-1852. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |