Published online Feb 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i7.1298

Peer-review started: December 2, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Revised: January 18, 2017

Accepted: February 7, 2017

Article in press: February 8, 2017

Published online: February 21, 2017

To systematically review literature addressing three key psychologically-oriented controversies associated with gastroparesis.

A comprehensive search of PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases was performed to identify literature addressing the relationship between gastroparesis and psychological factors. Two researchers independently screened all references. Inclusion criteria were: an adult sample of gastroparesis patients, a quantitative methodology, and at least one of the following: (1) evaluation of the prevalence of psychopathology; (2) an outcome measure of anxiety, depression, or quality of life; and (3) evidence of a psychological intervention. Case studies, review articles, and publications in languages other than English were excluded from the current review.

Prevalence of psychopathology was evaluated by three studies (n = 378), which found that combined anxiety/depression was present in 24% of the gastroparesis cohort, severe anxiety in 12.4%, depression in 21.8%-23%, and somatization in 50%. Level of anxiety and depression was included as an outcome measure in six studies (n = 1408), and while limited research made it difficult to determine the level of anxiety and depression in the cohort, a clear positive relationship with gastroparesis symptom severity was evident. Quality of life was included as an outcome measure in 11 studies (n = 2076), with gastroparesis patients reporting lower quality of life than population norms, and a negative relationship between quality of life and symptom severity. One study assessed the use of a psychological intervention for gastroparesis patients (n = 120) and found that depression and gastric function were improved in patients who received psychological intervention, however the study had considerable methodological limitations.

Gastroparesis is associated with significant psychological distress and poor quality of life. Recommendations for future studies and the development of psychological interventions are provided.

Core tip: Gastroparesis is associated with significant psychological distress and poor quality of life. Literature indicates that quality of life is lower in gastroparesis patients than population norms. Further, gastroparesis symptoms are adversely associated with increased anxiety and depression and impaired quality of life. Rates of psychopathology in gastroparesis cohorts range between 21.8% to 50%. Although a psychological intervention for gastroparesis has found improvements in depression and gastric function, it has not been replicated. Further research into potential mediating factors and the development of psychological interventions for individuals with gastroparesis is warranted.

- Citation: Woodhouse S, Hebbard G, Knowles SR. Psychological controversies in gastroparesis: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(7): 1298-1309

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i7/1298.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i7.1298

Gastroparesis is a gastrointestinal disorder involving delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction of the stomach[1]. Patients living with gastroparesis typically experience chronic nausea, vomiting, early satiety, postprandial fullness, and in some cases abdominal pain and fatigue[2-6]. The mean age of diagnosis ranges between 40-45.5 years, with 67%-88% of gastroparesis patients being female[5-12].

In Australia, the prevalence of gastroparesis is unknown, however in 2006 the Australian government provided an estimate that 120000 Australians suffered from severe gastroparesis[13]. The only study to investigate the prevalence of gastroparesis was conducted using medical records in Minnesota (United States) from 1996 to 2006. Jung et al[14] found that after adjusting for age and gender (to 2000 US Caucasians), the incidence of definite gastroparesis per 100000 person years was 9.8 in women, and 2.4 in men. In patients over the age of 60 years, the incidence peaked at 10.5 per 100000. It has been estimated that approximately one third of gastroparesis patients will be admitted to hospital for the condition[5], with a disease burden likened to that of Inflammatory Bowel Disease[14]. In terms of financial burden, Wang and colleagues[15] reported that in 1995 the costs of gastroparesis in the United States were 47.7 million dollars (primary diagnosis) and 863.3 million dollars (secondary diagnosis), while in 2004 costs were significantly higher at 208.3 million dollars (primary diagnosis) and 3.3 billion dollars (secondary diagnosis).

Individuals living with chronic gastrointestinal illness must make considerable physical, psychological, and social adjustments in order to manage their often debilitating symptoms[16,17]. Not surprisingly, patients suffering from chronic gastrointestinal conditions frequently report psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and impaired quality of life (QoL)[17-26]. With limited treatment options available for gastroparesis, the importance of psychological support or intervention has been repeatedly emphasized in the literature[8,27,28]. A systematic review of the gastroparesis literature exploring relationships between psychological distress, psychological processes, and gastroparesis has not yet been conducted.

The current systematic review will explore three key questions in relation to psychological features and processes associated with gastroparesis: (1) what is the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis cohorts and how does it compare to other gastroenterological conditions? (2) what are the levels of anxiety, depression, and QoL in gastroparesis cohorts and do they differ with respect to gastroparesis symptom severity, etiology, degree of gastric retention, and duration of symptoms/disease? And (3) do psychological interventions for gastroparesis patients reduce gastroparesis symptoms, anxiety, depression, and improve QoL?

For this review, a comprehensive search of PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases was performed. Search criteria used were: (“gastroparesis” OR “gastric delay” OR “gastric emptying” OR “gastric motility” OR “gastric timing”) AND (“anxiety” OR “affective state” OR “cognition” OR “control” OR “coping” OR “depression” OR “distress” OR “emotion” OR “helplessness” OR “illness perception” OR “life events” OR “mastery” OR “mental” OR “mood” OR “neuropsychological” OR “panic” OR “personality” OR “psycholog” OR “psychosocial” OR “quality of life” OR “self-efficacy” OR “stress”). Research papers retrieved through the search were also reviewed for further relevant references.

Inclusion criteria were: an adult sample of gastroparesis patients, a quantitative methodology, and at least one of the following: (1) evaluation of the prevalence of psychopathology; (2) an outcome measure of anxiety, depression, or QoL; and (3) evidence of a psychological intervention. Case studies, review articles, and publications in languages other than English were excluded from the current review.

Two researchers (Woodhouse S, Knowles SR) independently screened all references retrieved through the search and categorized them according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The researchers also extracted data from the papers independently, including participant information, methodology, assessment tools, and study outcomes.

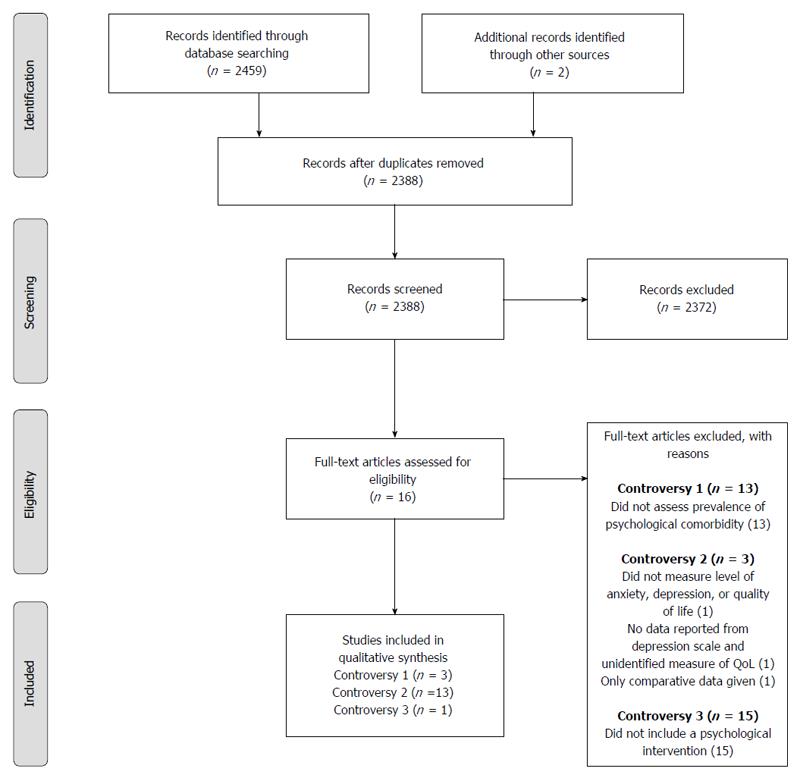

After 73 duplicates were removed, a total of 2388 citations were identified through database searches and review of other relevant references. Of these, 2372 were excluded due to: (1) not meeting the inclusion criteria; or (2) lack of information (Figure 1 for PRISMA diagram). This resulted in a total of 16 research reports which are summarized in Table 1.

| Ref. | Study characteristics | Participant details | Psychological measures used | Relevant findings | Conclusion |

| Soykan et al[6] | Cohort study using six-years of hospital records. Demographic and clinical data evaluated at entry to the hospital and most recent follow-up | n = 146 (120 females, 26 males). Mean age: 45.0 yr. Etiology: 42 DG, 52 IG, 19 post-surgical, 11 Parkinson’s disease, 7 collagen vascular disorders, 6 intestinal pseudo-obstruction, 9 other | CES-D, SCL-90 | 23% of IG patients were thought to be depressed, and 50% displayed significant elevations on gastrointestinal psychosomatic susceptibility | Psychological status may be predictive of response to prokinetic therapy |

| Harrell et al[31] | Cross-sectional study with an interview, patients classified into a clinical subgroup based on predominant symptoms | n = 100 (87 females, 13 males). Mean age: 48.0 yr. Etiology: unspecified | SF-12 | QoL (subscales and mental/physical component summaries) was significantly diminished in all gastroparesis patients when compared to population norms, but did not differ between groups based on predominant gastroparesis symptoms. QoL negatively correlated with physical symptom scores | Predominant-symptom classification may be useful in the management of gastroparesis |

| Bielefeldt et al[8] | Cross-sectional study with a qualitative interview | n = 55 (44 females, 11 males). Mean age: 42.4 yr. Etiology: 11 DG, 29 IG, 8 connective tissue disease, 4 post-surgery or trauma, 1 osteogenesis imperfect, 1 mitochondrial myopathy, 1 Marfan syndrome | HADS, SF-12, open-ended interview questions | Patients had moderately elevated scores for anxiety and depression, 74% met screening criteria for anxiety or depression, 29% were above the threshold for clinically relevant affective spectrum disorders, and eighteen patients were receiving chronic anti-depressant medication. Patients demonstrated impaired QoL compared to population norm, with no differences between etiologies. Physical symptoms were inversely related to the physical component score on SF-12. Symptom severity was positively correlated with depression scores, but not anxiety, symptom duration or degree of gastric delay. Qualitative data: patients were asked to describe the impact of gastroparesis on their lives and three main topics were identified: 1) eating out/social functions, 2) fatigue, 3) strain on relationships. Nausea and vomiting were the most troublesome symptoms, and patients also reported a fear of unrelenting disease, as well as frustration/dissatisfaction with healthcare providers | Gastroparesis treatment must focus on improving QoL. The results of this study provide support for the use of psychologically based interventions in gastroparesis |

| Jung et al[14] | Cohort study using medical records | Definite gastroparesis = 83 (68 female, 15 males). Mean age at onset: 44.0 yr. Etiology: 21 DG, 41 IG, connective tissue disease 9, hypothyroidism 1, malignancy 2, abdominal surgery 6, provocation drugs 19, end-stage renal disease 4 | None reported. Evidence obtained from medical records. | Of 83 patients with definite gastroparesis, 25 had evidence of comorbid psychiatric illness in their medical records. Twenty patients had "anxiety/depression" and five had "other" | Gastroparesis is difficult to manage and represents a major disease burden |

| Hasler et al[7] | Cross-sectional study. Data obtained from the Gastroparesis Registry | n = 299 (245 females, 54 males). Mean age: 43.0 yr. Etiology: 100 DG, 199 IG | BDI, STAI | Depression and anxiety scores increased with greater physician-rated, and patient-rated, symptom severity. Nausea and vomiting were greater in patients with more severe depressive symptoms. Bloating and postprandial fullness were greater in patients with more severe depressive symptoms, state and trait anxiety. Higher depression scores were associated with prokinetic or antiemetic drug use, and increased hospitalizations. Higher state anxiety was associated with anxiolytic use, while higher trait anxiety was associated with antidepressant use and increased hospitalizations. Depression and anxiety scores did not differ across etiology or degree of gastric retention. Higher symptom severity score was predictive of higher depression and state anxiety score. Use of anxiolytics was predictive of state anxiety, use of anti-depressants was predictive of greater trait anxiety score, and male gender was predictive of higher state anxiety | The physical and psychological features of gastroparesis both need to be considered in the development of individualized patient treatment plans. Longitudinal studies must be conducted to evaluate the relationship between psychology and gastroparesis, and whether psychological treatment can affect the physical symptoms of gastroparesis |

| Cherian et al[10] | Cross-sectional study | n = 68 (58 females, 10 males). Mean age: 42.6 yr. Etiology: 18 DG, 50 IG. 52 Functional Dyspepsia patients also studied | PAGI-QOL | DG patients scored significantly higher than IG patients on the following PAGI-QOL subscales: diet, daily activities, relationships. When pain severity was correlated with QOL subscales, there was a moderate correlation with avoiding physical activity, taking longer to perform daily activities, worry about having stomach problems in public, and depending on others to perform activities | Abdominal pain is an important symptom of gastroparesis and is associated with decreased QoL |

| Hasler et al[32] | Cross-sectional study. Data obtained from the Gastroparesis Registry | n = 243 (214 females, 29 males). Mean age: 41.0 yr. Etiology: 116 DG, 219 IG | PAGI-QOL, SF-36 | Patients had moderately impaired QoL, with inverse correlation to bloating severity | Bloating is a prevalent symptom in gastroparesis and is associated with impaired physical and mental QoL |

| Parkman et al[12] | Cross-sectional study. Data obtained from the Gastroparesis Registry | n = 243 (214 females, 29 males). Mean age: 41.0 yr. Etiology: 243 IG | BDI, STAI | 36% of participants demonstrated severe state anxiety, 35% demonstrated severe trait anxiety, and 18% demonstrated severe depression. Overweight IG patients were more likely to have an anxiety disorder. Major depressive disorder was associated with greater symptom severity. Anxiety and depression scores tended to be higher in patients with more severely delayed gastric emptying | Symptoms, gastric retention, current treatment, and psychosocial factors all play a role in the severity of IG |

| Jaffe et al[33] | Cross-sectional study | n = 59 (52 females, 7 males). Mean age: 43.0 yr. Etiology: 20 DG, 39 IG | PAGI-QOL, SF-36 | Nausea/vomiting subscale of PAGI-SYM correlated with lower scores on the PAGI-QOL. SF-36 scores were significantly decreased in gastroparesis patients compared to population norms | Nausea is a predominant symptom of gastroparesis that is associated with impaired QoL |

| Cherian et al[2] | Cross-sectional study | n = 156 (126 females, 30 males). Mean age: 41.1 yr. Etiology: 42 DG, 114 IG. 52 FD patients also studied | HADS, PAGI-QOL | Increased fatigue was associated with decreased QoL, increased depression, and decreased anxiety. All but one patient met criteria for depression, and the same was found for anxiety | Fatigue is a significant symptom in gastroparesis and is associated with decreased QoL. Psychiatric interventions may help in fatigue management |

| Hasler et al[29] | Cross-sectional study. Data obtained from the Gastroparesis Registry | n = 393 (327 females, 66 males). Mean age: 42.9 yr. Etiology: 137 DG, 256, IG | BDI, STAI, PAGI-QOL, SF-36 | Depression and anxiety were higher in those with greater symptom severity. Impaired PAGI- QOL and SF–36 physical component scores related to increased pain and/or discomfort severity | The influence of predominant pain/discomfort on disease severity is at least as great as predominant nausea/vomiting |

| Friedenberg et al[30] | Cross-sectional study | n = 255 (212 females, 43 males). Mean age: 42.0 yr. Etiology: 180 IG, 64 DG, 4 post-surgical, 7 other | PAGI-QOL | African American and Hispanic patients had lower scores on clothing and psychological PAGI-QOL subscales than Caucasian patients resulting in lower QoL overall. PAGI-SYM and PAGI-QOL had a negative correlation and 30% of the variation in QoL could be explained by symptom severity | Future population-based studies into the influence of race on symptoms and QoL in gastroparesis are warranted |

| Liu et al[36] | Randomized controlled trial with follow-up at 3, 7, 10, and 17 d post intervention | n = 120 (70 females, 50 males). Mean age: 60.5 yr. Etiology: 120 post-surgical | CES-D | A group that underwent a mental intervention had faster recovery from post-surgical gastroparesis (e.g., extubation time, eating recovery) compared to a control group. Depression was comparable in groups at baseline, but mental intervention group had lower scores than control at 3, 7, 10, and 17 d post-intervention | Mental intervention is important in post-surgical recovery, and primary nurses should be trained to care for patients physically and psychologically post-surgery |

| Pasricha et al[26] | Cross-sectional study. Data obtained from the Gastroparesis Registry | n = 262 (215 females, 47 males). Mean age: 44.0 yr. Etiology: 177 IG, 85 DG | PAGI-QOL, BDI, STAI | Mild improvement in QoL from baseline to follow-up at 48 weeks (PAGI-QOL and SF-36 physical and mental component scores), with no significant difference in QoL improvement across etiologies. No significant changes in depression or anxiety levels over the 48-week follow-up period. Moderate to severe depression and the use of anxiolytics at baseline were negative predictors of symptomatic improvement at follow-up, while anti-depressant use was a positive predictor | Less than a third of patients with gastroparesis experience symptomatic improvement over time and QoL remains impaired. Depression is an important predictor of symptomatic improvement |

| Cutts et al[34] | Cross-sectional study | n = 235 (186 females, 49 males). Mean age: 47.0 yr. Etiology: 125 IG, 68 DG, 28 post-surgical, 14 unspecified | SF-36 | Reports correlations between SF-36 subscales and gastroparesis symptoms. Negative correlations with Physical Function subscale: bloating severity, bloating frequency, epigastric pain severity. Negative correlations with Bodily Pain subscale: bloating severity, bloating frequency, epigastric pain severity, epigastric pain frequency, epigastric burn frequency. Negative correlations with Social Functioning subscale: epigastric pain frequency, vomiting severity. Negative correlations with Role Emotional subscale: bloating severity, bloating frequency. Negative correlation with mental health subscale: bloating severity. The only positive correlation was between the Role Emotional subscale and epigastric pain severity | Generic and global QoL tools may not accurately reflect the experience of gastroparesis patients |

| Lacy et al[35] | Cross-sectional study | n = 250 (196 females, 54 males). Mean age: 46.8 yr. Etiology: 126 IG, 37 DG, 34 post-viral, 17 post-surgical, 11 connective tissue disorder, 10 neurologic, 5 post-vaccination, 3 hollow visceral myopathy, 3 vascular, 4 miscellaneous | SF-36 | IG patients had higher physical functioning, mental health, and role-physical scores compared to DG patients. Patients with DG had lower physical component summary scores than patients with IG or other etiologies. Patients with IG had higher mental component summary scores than patients with DG or other etiologies | It is important that gastroparesis interventions aim to lessen pain and improve QoL in patients |

Of these reports, three (18.75%) identified the prevalence of psychopathology in a gastroparesis cohort[6,12,14], 13 (81.25%) assessed levels of anxiety, depression, or QoL[2,7,8,10,12,26,29-35], and one (6.25%) involved a psychologically-based intervention for gastroparesis patients[36]. A summary of the studies’ participant characteristics is presented in Table 2.

| n | |

| Number of studies included in this review | 16 |

| Number of participants identified in the studies | 2967 |

| Disease etiology | |

| Unspecified | 118 |

| Idiopathic | 1850 |

| Diabetic | 761 |

| Post-surgical | 198 |

| Other (e.g., connective tissue disorder, Parkinson’s disease) | 151 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 2434 |

| Male | 533 |

| Mean age | 44.6 |

Three studies reported on the prevalence of psychopathology in a gastroparesis cohort (n = 378). Using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and the hospital records of 52 idiopathic gastroparesis (IG) patients, Soykan et al[6] note that 23% had a history of depression or antidepressant therapy, and 50% displayed clinically significant somatization using the SCL-90. The authors state that somatization was higher in the IG population than in the gastrointestinal population, however the difference was not significant.

In an exploration of the epidemiology of gastroparesis, Jung et al[14] identified that 25 out of 83 patients with definite gastroparesis (30%) had evidence of psychiatric comorbidity in their medical records. Twenty of these patients had evidence of anxiety or depression, and five had other psychiatric illness. This study did not compare the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis to other gastroenterological cohorts.

In a larger sample of 243 IG patients, Parkman et al[12] identify comorbid major depression in 21.8% of patients, and severe anxiety in 12.4% of patients through face-to-face interviews between patients and study physicians or coordinators. This study did not compare the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis to other gastroenterological cohorts, however it was shown that females were more likely to report comorbid anxiety disorder than males, and patients with severe symptom severity or severe gastric retention were more likely to report major depression than those with milder symptoms. Participants in this study were mainly recruited from tertiary referral centers and therefore may not be representative of the general gastroparesis community.

Studies measuring anxiety and/or depression in gastroparesis cohorts: A total of six studies measured the level of anxiety and/or depression in gastroparesis cohorts (n = 1408)[2,7,8,12,26,29]. Of these studies, two used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[2,8]. Bielefeldt et al[8] used a cut-off score of > 8 and found that of the 55 participants, 74% met the criteria for either anxiety or depression, and 29% met the criteria for both conditions. No differences across etiology, gastric retention, or duration of symptoms/disease were reported, however symptom severity did correlate positively with depression score. Cherian et al[2] used a cutoff score of > 10 and found that of 156 participants, 99% met the criteria for depression and anxiety. Differences across etiology, symptom severity, gastric retention, and duration of symptoms/disease were not reported in the study.

A further four studies measured depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)[7,12,26,29]. Parkman et al[12] found that the average BDI score was 18.6 and 18% of the 243 IG participants fell into the range of 29-63 to indicate severe depression. Depression levels increased across mild to moderate symptom severity, however no difference was found in depression levels across degree of gastric retention. In a study of 299 gastroparesis patients by Hasler et al[7], BDI scores of ≥ 20 were present in 41.5% of participants. Higher BDI scores were associated with increased gastroparesis severity, nausea and vomiting, bloating, and postprandial fullness. The BDI scores were similar across diabetic gastroparesis (DG) and IG etiology, and degree of gastric retention. Self-reported gastroparesis severity and use of antiemetic/prokinetic medications were predictive of a BDI score ≥ 20. Another study by Hasler et al[29] did not report overall BDI scores, but compared scores across pain severity, etiology, and symptom predominance. Hasler et al[29] found that in a study of 393 gastroparesis patients, increased BDI scores were associated with greater pain severity in both DG and IG patients. The most recent study by Pasricha et al[26] identified that 41.6% of 262 gastroparesis patients had BDI scores greater than 20, indicating moderate to severe depression. Unlike the aforementioned studies, this study also examined the impact of duration of disease on gastroparesis outcomes, finding no significant change in depression levels after 48 wk of standard medical care for gastroparesis. However, depression level at baseline was a significant predictor of symptomatic improvement at 48 wk.

Finally, four studies used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to measure anxiety[7,12,26,29]. Parkman et al[12] found that the average state anxiety score was 45.2 while trait anxiety was 43.9. Using an STAI score of ≥ 50 to denote severe anxiety, Parkman et al[12] identified that 36% of 243 IG patients reported severe state anxiety, while 35% reported severe trait anxiety. State anxiety levels increased across mild to moderate symptom severity, however no difference was found in state or trait anxiety levels across degree of gastric retention. Hasler et al[7] noted that 50.2% of participants reported state anxiety ≥ 46, and 51.5% reported trait anxiety ≥ 44. Higher state and trait anxiety was associated with increased gastroparesis severity, bloating, and postprandial fullness. Increased self-reported gastroparesis severity and use of anxiolytic medications were predictive of higher state anxiety, while use of antidepressant medications was predictive of higher trait anxiety. State and trait anxiety were similar across DG and IG etiology, and degree of gastric retention. Hasler et al[29] found that increased STAI state and trait scores were associated with greater pain severity in both DG and IG patients. Finally, Pasricha et al[26] identified that 32.8% of participants reported state anxiety ≥ 50 at baseline, and 30.5% reported trait anxiety ≥ 50 with no significant change in state or trait anxiety levels after 48 wk of standard medical care for gastroparesis. However, use of anxiolytics at baseline was a negative predictor of symptomatic improvement at follow-up.

Studies measuring QoL in gastroparesis cohorts: Eleven studies included an outcome measure of QoL (n = 2076)[2,8,10,26,29-35]. The two earliest studies to measure QoL in gastroparesis used the SF-12. Harrell et al[31] found that in a sample of 100 gastroparesis patients, SF-12 subscale scores and component summary scores were significantly lower in gastroparesis patients when compared to population norms, with a negative relationship to upper GI symptom severity. Similarly, in a study of 55 gastroparesis patients, Bielefeldt et al[8] found that both the physical and mental component scores of the SF-12 were lower than population norms, with no significant difference between DG and IG groups. Symptom severity was negatively correlated with the physical component score. The authors also identified that nausea and bloating severity, combined with the HADS score for depression, best predicted the physical health component score of the SF-12. The influence of gastric retention and duration of symptoms/disease on QoL was not assessed in either study.

Of the five studies that used the SF-36, Jaffe et al[33] found that both the mental and physical component scores were impaired in a sample of 59 gastroparesis patients compared to population norms. The study indicated that nausea and vomiting severity was inversely related to QoL, with no significant difference in QoL between DG and IG patients, or across degree of gastric retention. In a larger study of 335 patients, Hasler et al[32] noted that physical and mental component scores were negatively correlated to bloating severity, with higher mental component scores predicting greater bloating severity. Another study by Hasler et al[29] identified that physical and mental component scores were lower in both DG and IG patients with increased pain/discomfort scores. Additionally, when comparing between pain/discomfort predominant versus nausea/vomiting predominant symptoms, pain predominance was associated with greater impairment in the physical component score.

More recently, Pasricha et al[26] identified mild improvement in SF-36 scores (physical and mental components) after 48 wk of standard medical care for gastroparesis. A 2016 study by Cutts et al[34] explored the relationships between symptom severity and the SF-36 subscales in a cohort of 235 gastroparesis patients, finding primarily negative correlations between symptom severity and Physical Functioning, Bodily Pain, Social Functioning, Role Emotional and Mental Health subscales (Table 1 for details). The only positive correlation was between Role Emotional and epigastric pain severity. Finally, the most recent study using the SF-36 was conducted by Lacy et al[35] and identified that in 250 gastroparesis patients, those with IG had better physical functioning, mental health, and role-physical than patients with DG. Similarly DG patients had lower physical component summary scores than patients with IG or gastroparesis from other causes, while DG patients and patients with gastroparesis from other causes also had lower mental component summary scores than those with IG.

Seven studies used the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders Quality of Life (PAGI-QOL) to measure QoL. Using this assessment tool, Hasler et al[32] reported impaired QoL in individuals with gastroparesis. Cherian et al[10] assessed QoL across etiologies and found that, in their sample of 68 patients, IG patients scored significantly lower than DG patients on PAGI-QOL measures of diet, daily activities, and relationships. In addition, significant negative correlations have been identified between the PAGI-QOL and total upper GI symptom severity[30], pain/discomfort severity[10,29], fatigue[2], bloating severity[32], and nausea/vomiting severity[33]. Similar to their findings using the SF-36, Pasricha et al[26] identified mild improvement in PAGI-QOL scores after 48 wk of standard medical care for gastroparesis. Despite these improvements in QoL over time, the authors note that QoL remained impaired in relation to the general population.

Only one study[36] involved a psychological intervention for gastroparesis patients. Liu et al[36] conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 120 post-surgical gastroparesis patients. Sixty patients were allocated to a control group that received conventional therapy (gastric tube, fasting, parenteral and enteral nutrition, routine nursing care, health guidance), while another 60 were allocated to a “comprehensive mental intervention” group that received conventional therapy in addition to: supportive mental consultation, bedside symptomatic mental intervention, music and abdominal massage, and mental intervention for patients’ families. While the groups had comparable CES-D scores at baseline, the mental intervention group scored significantly lower than the control group on days 3, 7, 10, and 17 after the intervention. The intervention group also had significantly improved gastric function following the intervention compared to the control group. The study did not include measures of anxiety or QoL.

Conclusions are presented according to the key questions of the systematic review. This is followed by a discussion of the strengths and limitations of the literature, and suggestions for future research in the area.

This review found three studies that investigated the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis patients. The reported prevalence of these psychopathologies were: combined anxiety/depression 24%[14], severe anxiety 12.4%[12], depression 21.8%-23%[6,12], somatization 50%[6], other 5%[14]. Parkman et al[12] reported that females were more likely to report comorbid anxiety disorder, and patients with greater symptom severity and gastric delay were more likely to report major depression. Soykan et al[6] identified a non-significant difference in the prevalence of somatization in the gastroparesis cohort compared to other gastroenterological cohorts, while Parkman et al[12] and Jung et al[14] did not make such comparisons.

It must be acknowledged that in addition to using the CES-D, Soykan et al[6] assessed whether patients had a medical history of either depression or anti-depressant use, which does not necessarily indicate prevalence of depression. Parkman et al[12] only reported on severe anxiety, which is likely to underestimate the prevalence of anxiety in the cohort, and two studies[6,12] only assessed psychopathology in IG patients so findings may not be representative of approximately two-thirds of gastroparesis patients. Finally, all three studies lacked clarity around how patients obtained a psychiatric diagnosis, and two[6,12] limited the psychopathologies that were included in the study. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that while there is psychopathology in gastroparesis patients, there has not been enough research conducted to provide a reliable prevalence rate. Further, no conclusion to date can be made with regard to whether rates of psychopathology are higher or lower in gastroparesis compared to cohorts that are healthy, chronically ill, or have other gastrointestinal conditions.

Overall, it is difficult to be definitive regarding the level of anxiety and depression in gastroparesis cohorts given the limited research conducted to date. Based on one study[12], 18% of gastroparesis patients have severe depression, 36% have severe state anxiety, and 35% have severe trait anxiety. Another study reported that 41.6% of patients had moderate to severe levels of depression at baseline, and identified that the percentage of patients scoring equal to or greater than 50 on the STAI at baseline was 32.8% for state anxiety, and 30.5% for trait anxiety[26]. While other studies also measured and reported on anxiety and depression, they did not identify levels of severity. Three studies[7,12,29] indicated that anxiety was positively associated with gastroparesis symptom severity , and one did not[8], while four[7,8,12,29] indicated that depression increased with gastroparesis symptom severity. Two studies reported on the influence of gender on anxiety and depression levels, with one stating that females displayed less clinically severe depression[12], and the other indicating that male gender was associated with higher state anxiety[7]. One study demonstrated that depression and anxiety levels were similar across DG and IG etiologies[7], and two showed consistency across degree of gastric retention[7,12]. Only one study[26] assessed the influence of duration of symptoms/disease, finding no significant improvement in anxiety or depression levels from baseline to follow-up at 48 wk. However, depression level and use of anxiolytics at baseline were significant predictors of symptomatic improvement at 48 wk.

The six studies that measured anxiety and/or depression in a gastroparesis cohort used a variety of assessment tools and cut-off scores, which makes it difficult to interpret the results as a whole. For example, the two studies employing the HADS each used a different cut-off score and did not give enough information to compare results across the studies. Similarly, of the four studies using the BDI and STAI only two reported the level of anxiety and depression in the sample, while the other two primarily used the scores for correlation analyses. Thus, although studies have been conducted on the severity of anxiety and depression in gastroparesis patients, the lack of consistency and scoring information limits the conclusions that can be made. With this being said, there is evidence to indicate that levels of psychopathology and gastroparesis symptom severity were positively correlated, and that this relationship tends to be consistent across the different forms of gastroparesis.

The eleven studies investigating QoL in gastroparesis demonstrated that QoL was lower in gastroparesis patients than population norms[8,31,33], and that there was generally a negative relationship between QoL and gastroparesis symptom severity[2,8,10,29-34], although one study found a weak positive relationship between the Role Emotional subscale of the SF-36 and epigastric pain severity[34]. Two studies found no significant difference in QoL between DG and IG patients[8,33], however one found that IG scored lower than DG on measures of diet, daily activities, and relationships[10], and conversely, another found IG scored higher than DG on both physical and mental components of QoL[35]. Only one study assessed the relationship between degree of gastric retention and QoL, with no significant relationship demonstrated[33]. One study assessed the impact of duration of symptoms/disease, finding a mild improvement in QoL after 48 wk of standard medical care for gastroparesis[26].

Based on these results, it can be concluded that QoL is lower in the gastroparesis cohort than the general population, and greater gastroparesis symptom severity is associated with lower QoL. At this point, there is not enough evidence to make conclusions about the influence of etiology, gastric retention, or duration of symptoms/disease on QoL.

Only one study has reported on a psychological intervention for gastroparesis patients. Liu et al[36] found that depression scores and gastric function were significantly improved in patients who received a psychological intervention compared to those who received standard care, however the study had considerable methodological limitations. Firstly, the study was conducted only on post-surgical patients, making the results difficult to generalize to other etiologies. The study also utilized a number of different factors in the intervention condition (e.g., supportive mental consultation, abdominal massage, music) making it impossible to ascertain the impact of any one component of the intervention. Additionally, the study did not utilize long-term follow-up. While the results of this study are promising, there is currently limited evidence for the use of psychological intervention in gastroparesis, and measures of other important psychological factors such as anxiety and QoL have yet to be assessed in this context.

Currently the literature indicates that QoL is lower in gastroparesis patients than population norms, and that as gastroparesis symptom severity increases, anxiety and depression also increase while QoL decreases. The studies are few in number, with variability in the assessments used and etiologies studied, making it difficult to form further conclusions. It also appears that five of the 15 studies[7,12,26,29,32] have used overlapping samples as they were all recruited via the Gastroparesis Registry. Consequently, findings may not be reflected across different samples. The evidence for the use of psychological intervention in gastroparesis is minimal and is further weakened by significant methodological limitations in the single relevant study.

Inconsistency in the assessment of gastroparesis must also be considered when interpreting these findings. While the majority of studies used self-report in conjunction with a scintigraphic study where > 60% retention at two hours, and/or > 10% retention at four hours indicated gastroparesis, there was some variation in assessment[6,8,31,34].

In order to move forward in understanding this area, future research would benefit from undertaking the following recommendations. When assessing the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis cohorts, studies should consider the broad range of psychopathologies, which should be diagnosed by an appropriately qualified individual. To gain greater insight into the relationship between psychological factors and gastroparesis, studies should use standardized assessment tools and cut off scores, and provide clear scoring information. Studies are also invited to look beyond basic correlation analyses, and explore possible mediating factors. Information regarding mediating factors would be especially useful in designing individualized psychological interventions for gastroparesis patients. To promote consistency and future comparison, recommendations for studies are summarized in Table 3, along with suggestions for the development of psychological interventions and future research questions.

| General recommendations: |

| Identify prevalence of psychological conditions based upon standardized and validated assessment tools (e.g., SCID[37], MINI[38]) |

| Use standardized assessment of gastroparesis (e.g., gastric emptying scintigraphy, PAGI-SYM[39]) |

| Use validated psychological scales to assess, anxiety, depression, stress (e.g., BDI[40], BAI[41], STAI[42], DASS[43]) and QoL measures relevant to individuals with upper gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., PAGI-QoL[44]) |

| Use and provide clear scoring information |

| Report assessment results in a manner that allows comparison across studies (e.g., standardized cut-off scores) |

| Psychological interventions: |

| Randomized control trial design |

| Prior to intervention, power analyses conducted |

| Clear details of intervention content made fully available to allow other researchers to review and undertake accurate replication |

| Gastroparesis-focused interventions |

| Include measures that assess a cost/benefit analysis, engagement of medical services |

| Where possible, patients, assessors, and statistician blinded |

| Independent evaluation of intervention session recordings to ensure protocol/treatment consistency |

| Psychological interventions need to be clearly identified and undertaken by trained and appropriately qualified individuals (i.e., psychologists, psychiatrists) |

| Identify clear inclusion and exclusion criteria |

| Identifying if (and where possible control for) participants have/have not received or are currently receiving psychotherapy (including type, duration etc.), using psychotropic medication, are on specialized diets for their gastroparesis |

| Utilize valid measures which can be accurately compared to other intervention studies |

| Evaluate participant engagement in therapy (e.g., % attendance to sessions, completion of homework) |

| Evaluate differences between completers versus non-completers |

| Include long-term post-therapy efficacy review time points (i.e., 1 and 2 yr post-intervention) |

| Future research questions: |

| What is the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis compared to other gastroenterological cohorts? |

| What psychological processes act as moderating/mediating factors between gastroparesis symptom activity and outcome variables such as QoL, anxiety, and depression (e.g., personality, coping style, self-efficacy)? |

| How may gender impact upon the presentation and course of gastroparesis and associated psychological distress? |

| How may historical and current stressors and/or traumas impact upon the presentation and course of gastroparesis? |

| To what extent does duration of symptoms/disease influence the relationship between gastroparesis and psychological distress? |

In conclusion, increased levels of psychopathology are evident in patients suffering from gastroparesis, with associations between the severity of psychological factors and the severity of gastroparesis symptoms. Although only one study has utilized a psychologically-based intervention for gastroparesis patients to date, the intervention was associated with improvement in both gastroparesis symptoms and levels of depression. The results of this systematic review indicate the importance of further research into the relationship between psychological factors and gastroparesis, especially given that current medical treatments for gastroparesis are limited. In particular, further exploration of the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis compared to other conditions is warranted, as well as an assessment of the factors that may mediate an individual’s ability to adapt to, and manage, gastroparesis.

Gastroparesis is a gastrointestinal disorder involving delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction of the stomach. Typical symptoms include: chronic nausea, vomiting, early satiety, postprandial fullness, and in some cases abdominal pain and fatigue. Patients suffering from chronic gastrointestinal conditions frequently report psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and impaired quality of life (QoL).

With limited treatment options available for gastroparesis, the importance of psychological support or intervention for gastroparesis patients has been repeatedly emphasized in the literature. This is the first systematic review of the literature to explore the relationship between psychological factors and gastroparesis.

This systematic review reveals that QoL is lower in gastroparesis patients than population norms, and that as gastroparesis symptom severity increases, anxiety and depression also increase while QoL decreases. Recommendations for the development of future research questions and psychological interventions are provided to encourage progress in this important research area.

The results of this systematic review indicate that further exploration of the prevalence of psychopathology in gastroparesis is warranted, as well as an assessment of the factors that may mediate an individual’s ability to adapt to, and manage, gastroparesis. Better understanding of these factors will assist in the development of targeted psychological support programs for the gastroparesis cohort.

This paper conducted for systematic review of psychological aspects of gastroparesis. Authors concluded that “gastroparesis is associated with significant psychological distress and poor quality of life. Recommendations for future studies and the development of psychological interventions are provided”.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Choi YS, Isik A, Okubo Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Tack J. Gastric motility disorders. Clinical Gastroenterolology and Hepatology. St Louis, MO: Elsevier 2005; 261-266. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Cherian D, Paladugu S, Pathikonda M, Parkman HP. Fatigue: a prevalent symptom in gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2088-2095. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang DM, Friedenberg FK. Gastroparesis: approach, diagnostic evaluation, and management. Dis Mon. 2011;57:74-101. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cherian D, Parkman HP. Nausea and vomiting in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:217-222, e103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1275-1282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, Kiernan B, McCallum RW. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2398-2404. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Hasler WL, Parkman HP, Wilson LA, Pasricha PJ, Koch KL, Abell TL, Snape WJ, Farrugia G, Lee L, Tonascia J. Psychological dysfunction is associated with symptom severity but not disease etiology or degree of gastric retention in patients with gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2357-2367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bielefeldt K, Raza N, Zickmund SL. Different faces of gastroparesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:6052-6060. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Borges CM, Secaf M, Troncon LE. Clinical features and severity of gastric emptying delay in Brazilian patients with gastroparesis. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:270-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cherian D, Sachdeva P, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Abdominal pain is a frequent symptom of gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:676-681. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Determinants of symptom pattern in idiopathic severely delayed gastric emptying: gastric emptying rate or proximal stomach dysfunction? Gut. 2007;56:29-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Parkman HP, Yates K, Hasler WL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Abell TL, McCallum RW. Clinical features of idiopathic gastroparesis vary with sex, body mass, symptom onset, delay in gastric emptying, and gastroparesis severity. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:101-115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 224] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Department of Health and Ageing. Enterra Therapy Gastric Electrical Stimulation (GES) System for the treatment of the symptoms of medically refractory gastroparesis. Canberra, ACT: HealthPACT, 2006. Available from: http://www.horizonscanning.gov.au/internet/horizon/publishing.nsf/Content/211ABF81A69CA39DCA2575AD0080F3DC/$File/HS Enterra Therapy.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Szarka LA, Mullan B, Talley NJ. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1225-1233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 361] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang YR, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis-related hospitalizations in the United States: trends, characteristics, and outcomes, 1995-2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:313-322. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 210] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moss-Morris R. Adjusting to chronic illness: time for a unified theory. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18:681-686. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Creed F, Levy RL, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, Naliboff BD, Olden KW. Psychosocial aspects of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3 ed. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press, Inc 2006; 295-368. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Aro P, Talley NJ, Agréus L, Johansson SE, Bolling-Sternevald E, Storskrubb T, Ronkainen J. Functional dyspepsia impairs quality of life in the adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1215-1224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ. Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a literature review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:225-234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, Fischler B, Demyttenaere K, Tack J. Abuse history, depression, and somatization are associated with gastric sensitivity and gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:648-655. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Haug TT, Wilhelmsen I, Berstad A, Ursin H. Life events and stress in patients with functional dyspepsia compared with patients with duodenal ulcer and healthy controls. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:524-530. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Frank L, Kleinman L, Rentz A, Ciesla G, Kim JJ, Zacker C. Health-related quality of life associated with irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with other chronic diseases. Clin Ther. 2002;24:675-689; discussion 674. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 161] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654-660. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 525] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Haag S, Senf W, Häuser W, Tagay S, Grandt D, Heuft G, Gerken G, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Impairment of health-related quality of life in functional dyspepsia and chronic liver disease: the influence of depression and anxiety. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:561-571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Glise H, Wiklund I. Health-related quality of life and gastrointestinal disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17 Suppl:S72-S84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pasricha PJ, Yates KP, Nguyen L, Clarke J, Abell TL, Farrugia G, Hasler WL, Koch KL, Snape WJ, McCallum RW. Outcomes and Factors Associated With Reduced Symptoms in Patients With Gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1762-1774.e4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rashed H, Cutts T, Abell T, Cowings P, Toscano W, El-Gammal A, Adl D. Predictors of response to a behavioral treatment in patients with chronic gastric motility disorders. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1020-1026. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Abell TL, Bernstein RK, Cutts T, Farrugia G, Forster J, Hasler WL, McCallum RW, Olden KW, Parkman HP, Parrish CR. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:263-283. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 261] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hasler WL, Wilson LA, Parkman HP, Koch KL, Abell TL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, McCallum RW, Sarosiek I. Factors related to abdominal pain in gastroparesis: contrast to patients with predominant nausea and vomiting. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:427-438, e300-1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Friedenberg FK, Kowalczyk M, Parkman HP. The influence of race on symptom severity and quality of life in gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:757-761. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Harrell SP, Studts JL, Dryden GW, Eversmann J, Cai L, Wo JM. A novel classification scheme for gastroparesis based on predominant-symptom presentation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:455-459. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hasler WL, Wilson LA, Parkman HP, Nguyen L, Abell TL, Koch KL, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, Farrugia G, Lee L. Bloating in gastroparesis: severity, impact, and associated factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1492-1502. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jaffe JK, Paladugu S, Gaughan JP, Parkman HP. Characteristics of nausea and its effects on quality of life in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:317-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cutts T, Holmes S, Kedar A, Beatty K, K Mohammad M, Abell T. Twenty-five years of advocacy for patients with gastroparesis: support group therapy and patient reported outcome tool development. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:107. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lacy BE, Crowell MD, Mathis C, Bauer D, Heinberg LJ. Gastroparesis: Quality of Life and Health Care Utilization. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu Y, Song X, Zhang Y, Zhou L, Ni R. The effects of comprehensive mental intervention on the recovery time of patients with postsurgical gastroparesis syndrome. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3138-3147. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | First MB, Spitzer RL, Miriam G, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute 2002; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22-33; quiz 34-57. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Rentz AM, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Tack J, Talley NJ, de la Loge C, Trudeau E, Dubois D, Revicki DA. Development and psychometric evaluation of the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index (PAGI-SYM) in patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1737-1749. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 218] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67:588-597. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3738] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3766] [Article Influence: 134.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893-897. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7560] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7648] [Article Influence: 218.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press 1983; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335-343. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6494] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6548] [Article Influence: 225.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | de la Loge C, Trudeau E, Marquis P, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, Tack J, Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D. Cross-cultural development and validation of a patient self-administered questionnaire to assess quality of life in upper gastrointestinal disorders: the PAGI-QOL. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1751-1762. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47017] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43253] [Article Influence: 2883.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |