Assessment of Whitehead Process Philosophy and Pedagogy in Nigeria: Implications for Global Citizenship among Teachers and Students ()

1. Introduction

In this paper, self-perception as global citizens among teachers and students is examined in the context of Alfred North Whitehead process philosophy. Global citizenship is considered crucial in this era of globalization driven by information technology. An individual’s patriotism to the world enables him or her to see humanity as one—to truly see the world as a global village—irrespective of distance, individuals love their neighbors as themselves. Global citizenship is indicated by patriotism—first to the nation, then to the world. It is assumed that with increases in the spread of information and education, there will be a communality in perception and understanding of humankind as it relates to fellow human beings and the environment. This increased awareness will motivate patriotism in the world and global citizenship—the ultimate reflection of globalization (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2017a).

But the plight for and movement toward globalization has not reduced discrimination among people. Divisions along the lines of tribe, race, region, and religion still abound, despite the increase in access to information and knowledge of the costs and consequences of their attendant destruction. Nonetheless, education—the reorientation of the mind—remains the permanent solution to these vagaries and vices in the world (Duncan, 2013; Magrini, 2009). Schools are one of the best locations for such reformations to take place (Pohan, 2012). What pedagogical approach or philosophy will suffice to stimulate teachers and learners to see the world—the harmony and interplay of its elements—truly as one and reduce the propensity of man to destroy it? What forms of education will stimulate students to learn and understand that the incidence of their actions or inactions has a ripple effect that could be globally far-reaching? What disposition do teachers, rather, students need to possess to perceive and preserve the unity of humanity despite its diversity? This study profiles Nigerian teachers’ and students’ sense of global responsibility against the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead.

Whitehead Process philosophy is the most modern of all process philosophies. It is the consummation of the belief that the current state of the world is in a dynamic state—in a state of flow, of evolution, in a “process” of “becoming” (Smith, 2010). To this effect, the world is always in a state of flux. Whitehead opposes the material or static state of existence and favors or proposes an organic metaphysical state. Like any organism, what affects one part affects the whole even while it is still growing, evolving, or developing (Monserrat, 2008; Sjostedt-H, 2016; Smith, 2010; Ugwuozor, 2019). Based on this belief, it is critical to note that there are ripple effects of global proportions for an action in one part of the world—the effect of an action or inaction could be adapted, replicated, or reacted to elsewhere, whether beneficial or harmful to mankind. This is the spirit of globalization, driven by rapid information dissemination and sharing. But the pedagogical structure in Nigeria to possess this mentality is indeterminate.

The current pedagogical approach among Nigerian teachers is often from the top-down, that is, teachers deliver the instructions and examine their students based on those instructions without effective student participation and contributions (Emeh, Abang, Asuquo, Kalu Agba, & Ogaboh, 2011; Ugwuozor, 2017). Most teachers are thus considered “banks” of knowledge from which the students may “withdraw” deposits (Freire, 1970). Nigerian students often study to pass their exams and may not learn to master the skills needed for their profession (Emeh et al., 2011). This teaching method still occurs despite popular calls for a “learner-centered” approach to teaching. Marina and Halpern (2011) argue that (time and other factors) constrain teachers to simply deliver learning contents as instructions to students for which they will be assessed during exams for their level of memorization rather than for understanding.

Students, therefore, tend to learn by rote and often have a narrow perspective on issues, lacking the capacity to relate to or translate the impact and implications of a local action abroad. Students may well receive instructions to satisfy the cognitive domain of learning bypassing their exams, but may lack the capacity to understand the global implications and applications of their learning—the affective. Thus, despite the apparent manifestation of globalization as evidenced in fashion trends, music, and other fads, the sense of global citizenship for these students in their various categories is uncertain. The extent to which people believe that an action in one part of the world can have effects or impacts in other places is largely unknown (Hill, 1999), since there is evidence of global conflict. There may be pedagogical implications of this effect. Since schools are a place for socialization of children and students (Theimann, 2016), they are also a place to teach global citizenship as teachers’ perceptions of themselves as global citizens are likely to stimulate students.

Substantial literature describes how the world is becoming a global village, and the factors that are responsible for this globalization, especially information technology (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2017a). To this effect, information and communication technology education is recommended. Few studies exist, however, that identify the determinants of potential global citizenship among teachers and students. For instance, critical thinking is determinant; and (UNESCO, 2017b) favors global citizenship education as influencers across cultures. No study, to the best of the author’s knowledge, has examined the potential for the global citizenship of students based on a philosophical framework. This study seeks to contribute to literature by identifying factors that may influence global perspectives of teachers and their students in southeast Nigeria by assessing the potential of students’ global citizenship through their perception of globalization given the current pedagogical approach in Nigerian schools relative to Whitehead Process Philosophy.

Results show that teachers perceived themselves to be global citizens more than students by believing that a local action can have an impact elsewhere and around the world. Students, on the other hand, possessed the potential for self-belief as global citizens in the sense that they listened more to the foreign media than to the teachers. Although of little magnitude, interacting more with foreigners will enrich this process.

The rest of the paper is written as follows: In Section 2, Whitehead Process Philosophy is briefly reviewed and its implications for global citizenship and ends with a conceptual framework for the study. In Sections 3 and 4 respectively, the model and data are described. The results and their implications are discussed in Section 5. The study concludes in Section 6 with summary of major findings and conclusions.

2. Brief Review of Related Literature

2.1. Whitehead Process Philosophy

This subsection describes first the fundamentals of Whitehead Process Philosophy. It also highlights variants of his proposition and current level of application toward global citizenship. Global citizenship includes the situation when individuals begin to see themselves as part of a global system. Ideologies and ideas that will bring about the increase in the social, emotional, and economic well-being of people should be prioritized. Thus the need for people to understand that the effect of actions or inactions to be globally far and wide-reaching is crucial to building momentum for global citizenship and participation (Ugwuozor, 2017). For this mentality to be imbued in human beings there has to be a philosophy that guides this frame of thinking. Process philosophy and its variants are considered the best in this context and demonstrate the need to assess the worldview of Alfred North Whitehead.

Much of this overview of Whitehead is drawn from Smith (2010) and Monserrat (2008). Whitehead’s work is reviewed here based on the following constructs or concepts: prehension, internal relatedness, and concrescence. These concepts are borne out of his concept of panexperentialism—the interpretation of the universe draws from its prehension and internal relatedness of world elements—so world elements are always in a state of “experiencing” and “becoming”. He had earlier indicated that nature is inert and that the universe consists of bits of matter that are extended, inert, lifeless, valueless, and purposeless. This he called scientific materialism but it did not survive the Darwinian evolution theory.

Plural nexus was his counter-response to scientific materialism from whence the theory of prehension and internal relatedness was conceived. He posited that within each man is a nexus of experience. He illustrates, for instance, that a rock is an accumulation and continuation of experiences molecular interaction for eons. Thus, the steady-state of the world is not an outcome of “survival of the fittest,” rather, while the world is always in a state of flux or becoming, the elements of the world more or less have been interacting to the point of “water finding its level”—a steady state (Smith, 2010). Nevertheless, the apparent steady-state nature of the world is still in the state of becoming—in the state of concrescence—such that the present world is connected to both the past and present, ad infinitum.

What then are the implications for pedagogy and learning? Many teachers do not teach students to discover and to identify themselves as part of a grand picture (Blackmore, 2016; Marina & Halpern, 2011). They often fail to communicate to students based on the subject they are taught that there are spatial and temporal effects of their actions and inactions. Students therefore should be taught to relate to the subject matter, irrespective of discipline, on how to perceive themselves as part of a process of becoming part of the world. Thus, students should be taught to know that their actions in situ have an impact in time and space.

Smith (2010) also notes that Whitehead preferred that students learn to harmonize their “aims” in life: initial aim, inherited aim, and adjusted personal aim. Smith also notes that Whitehead preferred students to learn to harmonize their “aims” in life: initial aim, inherited aim, and adjusted personal aim. A student possesses an initial aim that they may contrast between the ideal for a particular learning outcome and process, which may culminate in its realization; students may possess an inherited aim if and when they realize their role in a wider process of realizing an outcome, of becoming. For instance, Bill Gates and his team were part of a process that links the world together through information and communication technology. Therefore, students should be taught not to objectify the world as lifeless but that their learning or experience makes them significant contributors in a greater process of becoming.

Some other schools of thought agree with Whitehead, perhaps with a little variation. The pragmatist school of thought as supported by Kilpinen (2009) indicates that the process school of thought is evolutionary in nature after the order of Darwin. In Darwinian context, nothing is static—the world is dynamic.

Kilpinen (2009), citing the works of Dewey (1922, 2002: pp. 182-183), indicates that human habits are intrinsically situated but need to be formed—“knowledge is habit”. He posits that the difference between the mind of an infant and that of an adult is the level of formation due to habit so an adult may deal with more complex issues more than a child because the former has a better formed mind due to habit. This is the Process because as the concept implies, learning remains ongoing and cumulative to the extent that habits are formed. It also indicates, for instance, that a scientific man and a philosopher, like a carpenter, physician and politician, know their habit, not their consciousness. By implication, students should be taught to learn to elicit new habit formation; how the lessons or knowledge are transmitted is the gap in the observations of Kilpinen and Dewey.

Habermas’ (1998) social-communicative theory of rationality could provide the epistemological framework in which to gain further insight into the ongoing discussion. He defines rationality as interpersonal relationship and therefore it has a social aspect (Schaefer, Heinze, Rotte, & Denke, 2013). His work, The Inclusion of the Other, reveals the dissatisfaction with the traditional epistemology in which self-understanding reflects one universal worldview. For Habermas (1995, 1998), this conception of self or worldview is no longer adequate given the social and ideological pluralism, a fact I think Whitehead would concede as a metaphysical given. Communication for learning, therefore, is the fulcrum of Habermas (Hermann, 2017). He insists that the formation of subject (based on habit) is a communicative process since “men learn from each other”. Learning from one another, in turn, stimulates democratic ideals in the minds of people perhaps because no man knows it all and needs the knowledge of others (Cahn, 2004; Dewey, 1916; Papastephanou, 2017; Sandlin, Burdick, Norris, & Hoechsmann, 2012; Straume, 2016; Ugwuozor, 2016).

But whether teachers possess some of the elements of these philosophies is another matter. Often, discourse on philosophy is for intellectual purposes—for mental stimulation. Its application in the classroom or other theater of training is rare. Moreover, literature is rarer in the application of process philosophy for student learning of global citizenship. Far more of the literature on global citizenship is delivered by international donor agencies.

2.2. Overall Implications for Global Citizenship

International development organizations encourage young people to develop the knowledge, skills, and values they need to engage with the world, Oxfam (2017). Based on man’s apparent inhumanity to man and its attendant consequences, including terrorism, hunger, war, corruption, and death, these organizations have developed a template for global citizenship education to curb, if not to eliminate, this scourge. UNESCO (2017a) proposes three core conceptual dimensions of learning for education to be transformative (see Figure 1)—knowledge, socio-emotional, and positive change. Knowledge (cognitive) must touch the heart (socioemotional) and turn into action to bring about positive change (behavioral). They argue that the framework emphasizes an education that fulfills individual and national aspirations, and ensures the well-being of all humanity and the global community.

Another framework is recommended by Blackmore (2016). She argues that students should be taught critically to make them effectively engage with the world via a series of dialogue and reflective feedback, which, in turn, makes all parties in the conversation take responsible action (see Figure 2).

Based on these parameters, it can be assumed that the level of development in the developed world may suggest that global citizenship education is imbued in their curriculum. For instance, students are taught by default how to preserve their environment and the consequences of not doing so (Hill, 1999). Students are taught the various causes and effects of climate change—the effect of greenhouse gas emission due to industrialization, improper disposal of plastic and toxic wastes, and the resulting prevalence of flooding, deforestation, and desertification; ice melting at the polar regions, and wild fires, among others. The developed world possesses a better looking and conserved environment. The undeveloped world is more likely to destroy its environment due to lack of education than the developed world. Moreover, funds for environmental conservation flow from the developed countries.

![]()

Figure 1. Core dimensions of learning for global citizenship.

![]()

Figure 2. Framework for global citizenship.

What is not clear, however, is the impact of curriculum and pedagogy on a sense of humanity, especially in the current political climate and economy. While literature exists that agrees that an improved curriculum may translate to global citizenship (Peters, Britton, & Blee, 2008), the author of this study has yet to find literature about an experiment that has measured the translation of process pedagogy to global citizenship. Moreover, the global consciousness of global citizenship remains threatened by the politics that promote tension in race relations, on immigrants and immigration, on sexuality and sexual orientation, on international trade, and on terrorism.

Conceptual Framework

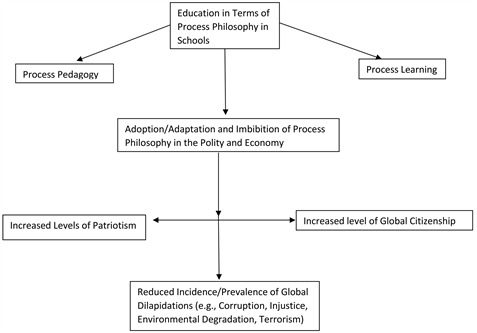

The author—a believer in Whitehead’s philosophy—accedes to the following:

· Education in terms of (Whitehead) Process Philosophy: pedagogy and learning in schools and elsewhere is motivated by the consciousness that every action has consequences that could be of global proportions and significance. This “mentality” will stimulate the understanding that good or bad actions will make the world a good or bad “becoming”.

· When this mentality or belief is adopted and assimilated in our daily processes, it becomes easy to see the world like an organism, a body where pain in one part affects the whole. This belief will stimulate patriotism and global citizenship. It will then become easier to perceive the prehension and internal relatedness of all elements that make up the material and metaphysical space of man.

· With increased level of patriotism and global citizenship, it will be easy to lure mankind away from vices that bedevil the global polity and economy. For instance, it may become easier to reduce, without force, the incidence and prevalence of global issues like corruption, environmental degradation, and terrorism, among others.

Source: Author’s original conception.

3. Model

Multinomial Logit Regression was used to identify determinants of self-perception as global citizens among the respondents. Respondents were classified according to their belief that an action committed locally may have ripple effects of global magnitude. Responses—dependent variables were categorized as “Yes”, “No”, and “Don’t Know” and, respectively, to indicate that their beliefs, non-beliefs, and indifference or ignorance. Independent variables included possible factors that could motivate such responses—for teachers: length of time as a teacher, motivation for teaching, frequency of trips abroad, and the highest level of education; for students: knowledge of current global affairs, if quality of education they receive may make them able to influence the world, their level of interaction with foreigners, confidence in achieving life aspirations, and if their favorite teachers have stimulated their global learning.

The probability of the outcome of the model—of the responses is stated:

(1)

where, i = cases, j = categories and k = independent variables.

Because parameter estimates of the model are often difficult to interpret and may not be intuitive appealing, the model is interpreted in terms of relative risk ratio or odds ratio. The model is specified thus,

(2)

which indicates that the probability of choosing j relative to 0 changes if we increase x by one unit. We then examine the probability of “Yes” and “Don’t Know” responses relative to “No” responses to the question on the effect of a local action abroad.

4. Data

Primary data were collected using questionnaires from students and staff of Peaceland College of Education, Enugu. The school possesses all attributes of higher education. It is affiliated with local and international universities and attracts staff and students from all walks of life. It is located in the heart of the Enugu metropolis and leverages the advantage that Enugu is former capital of Nigeria’s east central region.

Enugu remains the most developed city in southeast Nigeria. It is strategic in location because it is bounded by the north central region to Benue and other states of southeast Nigeria—Anambra, Abia, and Ebonyi. Residents are mostly students, civil servants, businessmen and farmers (in the hinterlands). Furthermore, it is the most peaceful capital of southeast Nigeria with drainage, roads, and an international airport.

Multistage sampling was used to select 100 students between 100 levels (freshman) and 400 levels (final-year students). The first stage required students to complete a listing in each level. Then, based on their population, a representative sample was selected. All levels had almost equal population; 25 students were selected from each level. Respondents were selected on a random basis in each stratum prior to the commencement of their compulsory lectures. All students had an equal chance of participating. Teacher-level data were collected from a simple random selection of all the teachers in the school according to a complete list of all the teachers.

Data were collected to measure proxies of variables peculiar to process ontology on panexperentialism: prehension, concrescence, and internal relatedness. On this basis, Whitehead is assessed on the level of perception of globalization and the sense of global citizenship. From the pedagogical standpoint, data were collected on pedagogical preference and its bearing on teachers’ and students’ perception of globalization and sense of global citizenship. Data were collected on the following: on factors that motivate teachers to teach whether they teach to stimulate students toward global citizenship or not; on the pedagogical preferences of teachers and students and whether their teaching style is participatory, learner- or teacher-centered; levels of interaction with foreigners to indicate their “appreciation” and “acceptance” of the views of people outside their frame of reference. Data were also collected on their listenership to local and foreign news and how interested they might be in their immediate and wider surroundings. Data were also collected on their self-perception as global citizens and the possible factors responsible for that perception. Self-perception as global citizen is indicated by the level of belief that an action or inaction in Enugu may have ripple effects in England and elsewhere in the overall global process of “becoming” or evolving. This is the crux of Whitehead’s organic process philosophy.

5. Results and Implications

In this section, factors that border on perception of teachers and students as global citizens are discussed within the framework of Whitehead process pedagogy. As a backdrop to determinants of teachers’ and students’ perception of themselves as global citizens, what motivates teachers to teach is discussed first, followed by the pedagogical preference among teachers and students. In Section 5.3 both groups are assessed on their frequency of international interactions to appraise their sense of globalization, and in the last section, details and determinants of global citizenship among the respondents are discussed.

5.1. Motivation to Teach

Forty percent of teachers teach to relate their lessons to a wider environment (see Figure 3). This category of teachers is likely to adhere to Whitehead process pedagogy. They are likely to stimulate the consciousness of students for relating these lessons to their immediate and wider community. What implications and applications might this hold for societal development? Most teachers however teach for “selfish” reasons. A significant proportion (34%) teach to learn more about the subject, perhaps, following the principle that “teaching is twice learning” and some others teach to discover more about themselves. This supports the fact that in Nigeria, teaching is a calling for the unemployed and underemployed. It is often a last resort for job seekers. Most of these teachers, therefore, may lack the capacity to transmit their lessons in a global way, that is, the content and illustrations of their lessons may not be globally far reaching. In the next section, pedagogical preferences among teachers and students are discussed.

5.2. Pedagogical Preferences among Teachers

Sixty-six percent of teachers prefer students to learn by doing their research and forming their own notes. This implies that students may possess the potential to discover the varieties of the subject matter outside of their immediate environment. But it is unclear if forming their own notes is not just for the sake of passing exams. Thirty-two percent of teachers prefer students to learn by reading only recommended texts and by forming their own notes. But how “global” or far-reaching the content of textbooks is will determine how stimulates a consciousness that the effect of a local action could ripple outward. Students who form their own notes may likely retain learning because of their ability to recast or rephrase the note contents. However, teachers (2%) who prefer students just to read recommended texts without forming their own notes are likely to make them learn by rote and will be less likely to stimulate them to “globalized” learning—to learn about the implications and applications of their lessons outside the classroom and in the world at large. Figure 4 shows the teachers’ pedagogical preferences.

5.3. Learning Preferences among Students

Figure 5 shows the students’ pedagogical or learning preferences. As with the teachers, a greater distribution (47%) prefers to form their own notes by reading

![]()

Figure 3. Factors that motivate teachers to teach.

![]()

Figure 4. Teachers’ pedagogical preferences.

![]()

Figure 5. Students’ preference for teachers’ pedagogical styles.

widely from many sources. This further validates the fact that students possess the potential for globalized and integrated learning, to understand the wider implication and applications of their disciplines. Forty-three percent of students prefer to read notes, handouts, and textbooks rather than do research—these students may simply read the required materials only to pass their exams. Less than 5% of students are global in their learning preference. That is, they were the only ones who preferred to be far reaching in their interpretations of what the teachers teach. It can be implied, therefore, that it is more convenient for students to be narrower in their assimilation of the subject than to investigate the subject in a wider, far-reaching manner. Some factors responsible for this approach might be time constraints (too many lectures) or because they have not found the right motivation for globalized learning.

5.4. Interaction with Foreigners

This subsection describes how students and teachers can be potentially globalized. This is indicated by their frequency of travel abroad (for teachers) and level of interaction with foreign students for cross-fertilization of ideas. Section 5.4.1 discusses how traveling abroad will likely influence process pedagogy and process learning among teachers and students respectively. Section 5.4.2 presents the same issue for students, but in terms of their interaction with foreigners (either by traveling abroad or meeting with foreigners in Nigeria).

5.4.1. Frequency of Foreign Trips among Teachers

Figure 6 shows that almost 70% of the teachers had never traveled abroad. Most of their information about foreign issues may be gleaned from the media. Only about 8% of the teachers traveled often and interacted with the wider world. This may not hold much promise in stimulating students’ global or worldview. Nonetheless, interacting with the wider world may not be limited to just foreign trips. Listening to foreign news and media may also bring the world into one’s home. Nonetheless, it is uncertain what makes a student or teacher more globalized, frequent direct interaction with foreigners or listenership to local and foreign media.

5.4.2. Students’ Interaction with Foreigners

Like the teachers who have never traveled abroad, most of the students have not interacted with their counterparts abroad. Figure 7 shows that only 6% of them claimed they did so often; about 53% did interact infrequently and 40% have never met students from foreign countries before. Exchange programs are often a good means of getting students to interact across the globe, for ideas to cross-fertilize, and for increased collaboration. But there are little data on schools that have exchange programs although there is anecdotal evidence for private schools that go on foreign excursions (Agarwal, Bansal, & Maheshwari, 2010). In any case, it can be assumed that students’ infrequent interaction with their counterparts abroad limits their potential for globalized learning and global citizenship.

![]()

Figure 6. Frequency of teachers’ travel abroad.

![]()

Figure 7. Students’ frequency of foreign interaction.

5.5. Global Citizenship

Global citizenship of students and teachers is assessed based on their listenership to local and foreign news and a comparison of their beliefs in globalization, that is, if they believed that what happens in Nigeria has an impact or implications elsewhere in the world. The determinant of their perception of globalization is assessed to identify factors that significantly influence such beliefs.

5.5.1. Listenership to Local News

Figure 8 shows that 65% of the teachers listen to local news very often while half of this number of students did not listen to local news. Almost 20% of students rarely listened to local news and 45% of them sometimes did. The higher listenership among the teachers may be attributed to age difference. Older people listen more to local news, perhaps, because of the need to follow issues in politics and economics. Younger people listen more to local news for entertainment (Wekesa, 2016). This may be further collaborated because political issues dominate most of the discourse during this period because of the electioneering among politicians in preparation for the next general election in 2019. FM stations are the most common outlets for news broadcasts and often offer contents on politics and entertainment (Wekesa, 2016). Moreover, more youthful students may find social media a more beneficial source of entertainment and information.

5.5.2. Listenership to Foreign News

Figure 9 shows that listenership to foreign news is about equal between students and teachers. Students’ regular listenership is marginally higher than the teachers’ (34% and 33%, respectively). Marginally higher listenership also exists for students among respondents who do not regularly listen to foreign media—about 49% of the students and 48% of the teachers. Among respondents who rarely listened to the foreign media, there were more teachers (19%).

![]()

Figure 8. Listenership to local news between students and teachers.

![]()

Figure 9. Listenership to foreign news between students and teachers.

With these findings, it is inconclusive to appraise a more globalized respondent category. However, identifying what factors may motivate either students’ or teachers’ listenership to foreign media will be crucial to assessing their potential for global citizenship.

5.6. Self-Perception as Global Citizens

This subsection is the most direct proxy measurement for absorbing Whitehead Process Philosophy. Figure 10 shows that 62% of the teachers are considered “global” in their teaching; teachers who believe and prefer to deliver their lessons in terms of their impact and implications in Nigeria and abroad. This implies that they relate current state of affairs in Nigeria to what is happening abroad to buttress the impact of their lessons. Thus, they may relate to local and foreign events to illustrate their lectures. Conversely, the distribution of students who believe that actions here have an impact outside Nigeria are fewer. About 40% of them claim they don’t know about possible effects on local actions abroad and 38% indicated they did. This may suggest that lecturers find it difficult to transmit their global awareness to the students; however, determinants of global citizenship among students and teachers are discussed in the next section.

5.7. Multinomial Logit Regression

In this section, the determinant of global citizenship among teachers and students is estimated with a discrete choice model—the multinomial logit model. Table 1 and Table 2 show estimates for students; estimates for teachers are in Table 3 and Table 4.

5.7.1. Multinomial Analysis for Students

Table 1 shows students who are knowledgeable about global current affairs and interact often with their international counterparts, relative to those who are not knowledgeable and do not interact, are more likely to be globalized in their perception of the world, and are more likely to believe that actions in Nigeria have impacts and implications abroad. However, students who interact more often with their counterparts abroad are more likely to possess a neutral perception on globalization than those who do not believe that what happens in Nigeria has effects abroad.

Because parameter estimates are not the most intuitively appealing for interpreting multinomial logit model, the probability of the respondents’ characteristics to influence their perception on globalization relative to not doing so is estimated in Table 2.

5.7.2. Relative Risk Ratio Estimates for Students

Table 2 shows the likelihood of students’ knowledge of global current affairs increased their belief in globalization—what happens in Nigeria influences or has an impact elsewhere in the world—by 34 times, and vice versa. Also, students who interacted more with foreigners are likely to believe what happens locally has an international impact 9 times more than those who did not. Nonetheless, by the same magnitude, students who interacted more with their foreign counterparts are more likely to be indifferent or neutral about the impacts and implications of local actions abroad than those who do not believe.

![]()

Figure 10. Global Citizenship: Student-Teacher beliefs on global effect of a local action.

![]()

Table 1. Parameter estimates for students. Dependent variable: Belief that what happens in Nigeria has an effect abroad [Base Reference: No].

[* = significant at 10%, ** = significant at 5%], No. of Observations = 47, LR χ2 = 17.48, Prob > χ2 = 0.064, Pseudo R2 = 0.175.

![]()

Table 2. Relative risk ratio. Dependent variable: Belief that what happens in Nigeria has an effect abroad [Base Reference: No].

[* = significant at 10%, ** = significant at 5%], No. of Observations = 47, LR χ2 = 17.48, Prob > χ2 = 0.064, Pseudo R2 = 0.175.

![]()

Table 3. Parameter estimates for teachers. Dependent variable: Belief that what happens in Nigeria has an effect abroad [Base Reference: No].

[* = significant at 10%, ** = significant at 5%], No. of Observations = 47, LR χ2 = 17.48, Prob > χ2 = 0.064, Pseudo R2 = 0.175.

![]()

Table 4. Relative risk ratio. Dependent variable: Belief that what happens in Nigeria has an effect abroad [Base Reference: No].

[* = significant at 10%, ** = significant at 5%], No. of Observations = 47, LR χ2 = 17.48, Prob > χ2 = 0.064, Pseudo R2 = 0.175.

To gauge the ripple effect of local actions internationally may depend on the level of interactions among the students. Students who interact on a micro level—those who interact with very narrow concepts—may not see the likelihood of any consequence of a local action internationally. Also, those whose mentality is not “global” in nature also may not possess a mindset that translates local actions and international consequences. For instance, students who prefer to emigrate abroad because of their local societal vagaries may not relate or translate the consequence or effect of the actions that took place where they are to where they intend to emigrate. For example, of what consequence is the embezzlement of education funds Nigeria, which affects them directly, affect the quality of education they intend to pursue in Norway?

At the micro level, this may be difficult to determine directly or indirectly or in the short- or long-term, but one who possesses a “global” perspective may observe, through international relations, the meso- and macro-consequences of local actions internationally. An accumulated effect of embezzlement that leads to underdevelopment, which, in turn, may force students to (illegally) emigrate may elicit negative reactions from their host countries through anti-immigration policies. Immigrants are often vulnerable to violence, murder, racism, terrorism, and a host of other vices.

5.7.3. Multinomial Logit Estimate for Teachers

Table 3 parameter estimates for teachers suggest that the rationale for teaching and level of education did not influence their global outlook on life nor their pedagogy style. More teachers were unlikely to increase their global outlook by 1.2 units for every unit increase toward realizing their goals for teaching. Level of education did not influence teachers’ globalized outlook. Furthermore, teachers who were likely to be indifferent to issues of globalization relative to those who did not believe in it were likely to decrease by 4.5 units for every unit increase in their ranks for anyone with higher education. But as noted earlier, parameter estimates of multinomial logit model are limited in explaining the relationship between dependent and independent variables. The probability of teachers possessing a global outlook to life relative to not possessing it is estimated in the next section.

5.7.4. Relative Risk Ratio Estimates for Teachers

Estimates of the Relative Risk Ratio show, in Table 4, that motivation for teaching and level of education significantly influence globalization outlook and pedagogy among teachers in a paradoxical sense. Increased motivation to teach reduces the likely belief in “globalized” perspective to teaching. Motivation to teach reduces the probability that teachers would support a globalized approach to teaching by 0.3, rather than not support it. This implies that teachers who are more motivated to teach, although believing by default in process philosophy, are less likely to teach in the context of globalized learning than those who do not. Similarly, a higher level of education reduces the probability that teachers would support a globalized approach to teaching by 0.03, rather than not support it. In this regard, teachers with a higher level of education who implicitly adhere to process philosophy—and believe that a local action may have an effect elsewhere in the world—are less likely to teach in this manner than those who do not. Possible reasons could include insufficient interaction time between students and teachers. Mumtaz (2000) argues that insufficient time is a limitation to participatory learning and action. Thus, teachers are often constrained to deliver instructions on the content (cognitive) rather than expounding on the subject with global illustrations (affective).

6. Summary and Conclusion

Major findings of this paper concern globalized pedagogy and learning between teachers and students in Nigeria. The paper assesses the actual and potential beliefs about the effect of an action in situ elsewhere in the world and its implications for teaching and learning. First, teachers were assessed on the motivation to teach, and 34% of them did so to learn more about a subject. Forty percent of them taught to discover the wider world. This, however, does not suggest they knew or taught students about the effect of a local action abroad.

Then, both teachers and students were assessed on pedagogical preferences. Most of the teachers preferred their students to learn more about their subject by doing research and forming their notes. Most students, on the other hand, preferred to form and read their notes strictly for exams. Very few preferred to learn with illustrations of and applications to global issues.

Similarly, both categories of respondents were appraised on their levels of interaction with foreigners. Most of the teachers had never traveled abroad and likewise, very few students ever interacted with foreigners. On this note, it may be concluded that both teachers and students were not globalized and may not believe in the effect of a local action elsewhere in the world.

But traveling abroad or interacting with foreigners may not suffice for global citizenship. Thus, students and teachers were assessed on their listenership to local and foreign media—since they could not directly interact with the wider world, the paper also assesses how they did so indirectly via the media. Results show that teachers listened to more local media than students, but students marginally listened to more foreign media than teachers.

Last, students and teachers were assessed on their self-perception as global citizens—if they believed that an action at home may have impact abroad. This question is the most direct proxy measure of Whitehead Process Philosophy. Sixty-two percent of teachers and 38% of students did not believe they were global citizens. This result therefore suggests that teachers are more globalized than students. But whether this belief is reflected in their teaching is another matter. Moreover, it was necessary to identify the factors responsible for this belief.

Students and teachers were therefore examined on determinants of global citizenship. Knowledge of global current affairs and levels of interaction with foreigners were significant determinants among the students. For teachers, motivation for teaching and level of education were significant factors that did not influence their self-perception as global citizens. Only duration in the teaching profession was a factor, but it was not significant. Further, there was more likelihood for teachers that believe in globalization not to express this belief relative to those who did not. The rationale for this belief needs further examination. However, literature (for example, Appel, Buckingham, Jodoin, & Roth, 2012) suggests that insufficient contact time with teachers could be a factor that hindered “participatory” and global citizenship education.

Nonetheless, the results have shown the possibility of global pedagogy and learning. Teachers possess the potential to stimulate students about globalized thinking—that a harmful action in situ could be of global consequences in time and space—and, similarly, for beneficial actions. It is possible, therefore, from a philosophical standpoint, to persuade students toward altruistic and patriotic actions: toward environmental conservation and protection; improved and healed differences in race, religion, and region; toward less greed and corruption; and advancing further to restore human dignity with little or no cost to life and livelihood. Perhaps policymakers can be persuaded to integrate this idea into the school curriculum to help students gain better awareness of their connectedness. This consciousness would enhance students’ cognitive development and observational skills (Pyle, 2002), encourage future generations to start to live, not just simply exist in their environment, and is likely to reduce or eliminate bullying (Malone & Tranter, 2003). It would help students understand the world around them by shaping their behaviors to appreciate and preserve their surroundings (trees, animals, human beings, etc.) for what they are, rather than change them merely to meet their own needs. Such thinking, woven into a school curriculum, can become an integral element in communicating sustainability values. When people feel connected to someone or something, they are more likely to work hard to secure and preserve it.

This study concludes that, by default, teachers possess more potential than students to adopt and adapt Whitehead Process Philosophy and Pedagogy. Thus, it is possible for students and the rest of the society to be trained to understand the prehension and internal relatedness of the elements of global systems so the outcome of one’s action (and inaction), while not directly or immediately affecting the individual, could affect people and things elsewhere which they may be unaware of—a process way of thinking.

Process mentality—belief in global citizenship—enhances one’s ability to see the world and humanity as one interrelated unit. It is possible from the study’s findings that increased motivation to teach and higher level of education will stimulate process thinking.

Recommendations

The world is becoming increasingly globalized in a market-driven sense without any clear-cut underlying philosophy. In fact, the dominant philosophy, in the author’s opinion, is one of maximizing self-interest as the current global polity and economy demonstrate. Leading developed nations are striving for greater self-determination and influence as exemplified by the United Kingdom and the United States in the Brexit (Britain’s exit from the European Union [EU]) and MAGA (Make America Great Again slogan of the Trump Administration). Many influential political parties within the EU are clamoring for less immigration into their countries, which has produced more anti-immigration policies. These policies adversely affect legal migrants of these countries and the latter may react negatively (in severe cases, through terrorism) to new immigrants; the extent to which immigrants are safe may depend on their wealth and influence.

The push for immigration from developing countries is often a result of corrupt leadership and fear of criminal retribution. In addition, often political leaders in developed countries do not provide adequate infrastructure needed for development. Resources are often misallocated and public funds embezzled. Consequently, there is strife for scarce resources that culminates in extreme negative consequences. In all these scenarios, there is complete absence of Process Philosophy (the effect of a local action could be of global consequence), which hurts everyone.

The belief that the world is one, as humanity is one, is not universal. This study recommends that teachers should be further motivated and trained to impart the study of process philosophy. This philosophy should be a core rather than elective course in the colleges of education that train teachers. Teachers should be highly encouraged to interact directly with the wider world through foreign trips and exchange programs. Teaching should not be a mere job for the unemployed and the underserved. Ideally, students and the wider community will learn to understand, rather than to underestimate, their roles and contributions to a world that is constantly in a state of “becoming”.