Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

The public housing sector in Italy faces a generalized crisis, which does not spare the issue of architectural and urban quality, both in the (relatively few) new buildings realized over the last three decades, and in increasingly frequent regeneration actions. The latter – the subject of this essay – generally do not go beyond conventional maintenance and are typically limited to applying essential technical solutions for energy efficiency. They miss the opportunity to update the building stock to address current housing needs. Against this backdrop, the case of SINFONIA – a five-year project financed by the European Union – represents a relevant exception. The paper presents two recent housing renovation actions developed within SINFONIA and conceived by AREA Architetti after winning two design competitions. Both actions interpret conversion in the most inventive ways, demonstrating an aptitude for a real aesthetic rethinking that changed the appearance of the buildings experimenting with two profoundly different design approaches: reinterpretation and metamorphosis. In presenting the two actions, this essay reflects on the procedure and design lessons to be learned from this experience for transfer to other situations.

In the last three decades several innovative design solutions have emerged in most European countries for renewal of their public or social housing stock, upgrading it to current needs in terms of spatial, functional, aesthetic, and environmental requirements.1 Many experiences have been encouraged at European Union level, often supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). In parallel, the Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities (2007) and the Toledo Declaration (2010) established goals regarding urban regeneration issues, in which the public housing sector plays a relevant role. More recently, attention was revived by the New European Bauhaus project (2020), launched by the European Commission in close connection with the Horizon Europe work program (2021–27) and coherent with the Sustainable Development Goals listed by the United Nations (2019). Despite this encouraging framework, Italy is increasingly distanced from most European countries: the public housing sector is at the height of a lengthy generalized crisis that affects (also) architectural and urban quality, both in the (relatively few) new buildings realized in the last thirty years, and in renovations.2 The latter and the subject of this essay generally do not go beyond conventional maintenance and are typically limited to applying essential technical solutions for energy efficiency, adopting a conservative, purely technical, and uninspired design approach. They miss the opportunity to update building stock to current housing needs, responding to the spatial and aesthetic issues – along with energy-saving requirements – that strongly impact the lives of residents.

The results across the Italian peninsula are not remotely comparable to other European countries and their more exciting experimental housing regeneration projects.3 This lack of design vision is the result of years of disinvestment by central and local public administrations, which has triggered severe material and social issues. The combination of obsolete housing stock – in metropolitan areas, more than 38% predates the 1970s – and insufficient public housing supply 4 further highlights the unexpressed potential thus far. A lack of funding only partially explains this withdrawal: a crucial role derives from the conditions within which the interventions are conceived and designed – including the absence of a widespread design culture. Yet, the transformative potential would be high, as proven by the growing European actions and the echo they produce within the architectural debate. Mass-housing renovation projects have indeed come to influence the awarding of major international industry prizes. For example, in France, numerous building and city-scale realizations have been implemented in the last three decades – probably starting with the “Banlieues 89” experience.5

They include pioneer interventions like those by Atelier Castro Denissof in Villeneuve-la-Garenne or Lorient, and recent well-known projects such as those designed by Druot, Lacaton & Vassal 6 in Paris, Saint-Nazaire, and Bordeaux. The latter – the transformation of three social housing buildings of 530 dwellings – was awarded the Mies van der Rohe European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture. Lacaton & Vassal’s innovative approach to transformation was one of the main reasons for the accreditation that garnered them the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2021. Good practices are also prolific in The Netherlands. Among the widespread actions – often with above-average results – the Bijlmermeer district on the outskirts of Amsterdam is an emblematic case study. Over the past thirty years, multiple intervention strategies have been tested on the monumental buildings that form this Modernist complex. These include radical approaches, such as the transformation of the Florijn Block, remodeled through partial demolitions and the insertion of new low-rise blocks by Vanschagen Architecten, a firm specialized in innovative renovations, including a residential building in Klarenstraat, winner of the 2015 Amsterdam Architecture Prize.

Another building in the Bijlmermeer district has recently undergone a “light” transformation. In the DeFlat Kleiburg project, XVW Architectuur and NL Architects retained the entire existing volume, simply reconfiguring the ground floor and de-standardizing the layout of the dwellings. Again, this less radical strategy was awarded the Mies van der Rohe Prize in 2017. The issue of public housing stock renovation in Italy has become more topical than ever due to significant recent economic opportunities – supported mainly by the Piano Nazionale di Recupero e Resilienza (PNRR) [National Recovery and Resilience Plan] approved in June 2021; a local response to the Next Generation EU fund.

In particular, public housing authorities have been recently provided with:

(1) “super bonus” tax relief, consisting of a 110% deduction of costs for implementing specific interventions aimed at energy efficiency and static consolidation to reduce seismic risk,7

(2) the Programma Innovativo Nazionale per la Qualità dell’Abitare [National Innovative Programme for Quality Living] aimed at upgrading and increasing social housing stock, regenerating its socioeconomic context, improving its safety and accessibility, and supporting the reuse of marginal public spaces and buildings,8 and

(3) the Sicuro, verde e sociale: riqualificazione dell’edilizia residenziale pubblica [Safe, green, social: redevelopment of public housing] program, financed with resources made available by the PNRR Supplementary Fund.9

The pressing deadlines for deployment of funds, dictated by the Next Generation EU rules, have meant that much of the design work has already been started or even completed – over a period of 12– 24 months. The design outcomes are not yet accessible,10 although the consensus among many in the industry is that too much has been rushed through, showering funds on a sector no longer used to handling such investments without time to plan properly for the best solution. Moreover, the tight schedule for accessing funds has often compressed timing of the design phase, with the risk of relegating the quality of architectural design to a subordinate role with respect to other issues. In any case, successes and failures caused by this unexpected contingency will be appreciated in the coming years and will likely become a research subject. However, it seems fair to say that the effects of this downpour of funding will open new scenarios for the public housing sector, offering a chance to discuss these issues at a higher level in the near future. These multiple issues have been explored in research developed by Politecnico di Milano’s Department of Architecture and Urban Studies within the Territorial Fragility project (2018–22). A specific partnership was established with Federcasa,11 the national association that brings together most Italian public housing agencies (ATER), to raise awareness for improving architectural and urban design quality.12

The above-mentioned aspects lay the foundations for a significant exception, the SINFONIA, a five-year project financed by the European Union to put in place large-scale, integrated, and scalable energy solutions in mid-sized European cities. It could be considered a pioneering case in Italy even if – and probably precisely because – it is in a border region with its own statute. The following paragraphs will present two projects of the five developed as part of this action. This essay will reflect on the lessons that can be learned from this experience as a contribution to the hoped-for development of an Italian way of architectural and urban regeneration.13

The success of this initiative is considered mainly from a disciplinary point of view here. Primarily, by considering the procedural premises detailed in the following pages which outline a partnership between various local stakeholders that obtained public funding on the basis of a successfully evaluated project, the selection of the design solution through an architectural competition, the implementation of the interventions on schedule, and achieving the expected results. Given these starting conditions, the success then extends to the ability of the designers who were able to move skilfully in the (little) space left by the many constraints, without leveling down to the fulfillment of a technical/performing service, nor even limiting themselves to an adaptation as close as possible to the original conditions and setting aside the expression of an architectural idea. Instead, the designers showed an inventive capacity in proposing their vision,14 overlapping the pattern of the original project and bringing into play their compositional skills in the process of reconquête du banal.15 Therefore, the emphasis here is not on the success of the formal outcomes – the evaluation of which would be too subjective – but on acknowledging a leading role attributed to the architectural design.16

SINFONIA PROJECT

SINFONIA (Smart INitiative of cities Fully cOmmitted to iNvest In Advanced large-scale energy solutions) 17 is a five-year EU-funded project launched in June 2014 to implement scalable energy-saving solutions in medium-sized European cities by developing integrated urban strategies to transition to a low-carbon economy. The project relied on cooperation between two pioneer cities, Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) and Innsbruck (Austria), and five “early adopters” who were interested in raising awareness reciprocally. The shared goal was to test strategies to achieve between 40% and 50% of primary energy savings and increase the renewables share by 20% within several demonstration sites selected in the two leading cities. A series of integrated measures was planned to achieve these goals, supported by an EU-funded investment covering 20% of the costs of:

(1) collective housing renovation,

(2) power grid optimization, and

(3) district heating network development.

Focusing on the Bolzano case, the actors involved were the City of Bolzano; the local electricity supplier SEL (South Tyrolean Electricity Company); Agenzia CasaClima – engaged in the definition and certification of energy requirements to be pursued in refurbishment projects; EURAC Research –in charge of monitoring energy consumption and occupant habits for at least one year after completion; and WOBI-IPES, the Autonomous Province of Bolzano’s Social Housing Institute, which played a crucial role in project implementation, considered the centrality given to public stock in fulfilling the goals. The project involved selected regions within the municipality where a significant development of the district heating network increased the share of renewable energy sources – together with the development of a series of urban mobility infrastructures. The renovation of social housing stock was parallel on five demonstration sites built between the 1950s and 1970s, comprising approximately 350 WOBI-IPES dwellings: Via Palermo 74, 76, 78, 80 (thirty-eight dwellings); Via Brescia 1, 3, 5 and Via Cagliari 10, 10A (106 dwellings + ten resulting from the attic floor elevation); Via Similaun 10, 12, 14 (fifty-nine dwellings); Via Aslago 25, 27, 29, 33, 35 (seventy dwellings + fourteen added by attic elevation); Via Passeggiata dei Castani 33 (seventy dwellings). Despite differences in size, age of construction, building type, and architectural features, all the actions shared two equally essential measures: the insulation of the building envelope and the integration of renewable energy sources – for the production of electricity, thermal energy, and domestic hot water. A third intervention, limited to two of the five sites, addressed the addition of an extra floor on the roof, increasing the number of public dwellings thanks to a local planning law that allows an additional 20% volume for such actions.

Completing the SINFONIA project brought significant benefits to tenants by improving dwelling comfort and ensuring cost savings thanks to noticeably reduced energy consumption – it is worth mentioning that the cost of utilities can often be far higher than the rent for the least affluent tenants, dramatically impacting housing affordability. Moreover, ensuring tenants do not have to leave their homes during renovation work is certainly a key condition, influencing design and execution choices as well as limiting design options, such as dwelling reconfiguration. None of the interventions put in place required tenants to move permanently or temporarily. This is particularly important in contexts where there is not enough public housing to allow turnover – and most Italian cities are in this situation. Keeping tenants in their homes also has advantages such as avoiding the disruption of solidarity networks in neighborhood communities. Given this choice (or condition), specific measures were applied to ensure minimum impact on residents during construction.

A series of meetings were planned to accompany the renovation process, explaining goals and sharing doubts and needs; a dedicated mailbox was installed on the building site to collect requests and connect residents, contractor, and housing agency; to improve safety, every worker who had access to the building, stairs, and balconies, wore an ID number on their vest; TV antennas were repositioned in a very short time to avoid even minor inconveniences. The temporary removal of the lifts to be replaced required the installation of temporary devices along the scaffolding, operated by a contractor employee. In addition, demo dwellings were set up to illustrate interventions and explain how to use the new technologies.18 The European-funded project, the clarification of defined quantitative goals, the role played by the actors involved, data describing size, and the scale of interventions all provide a framework for a better understanding of the subject of this essay: the opportunity for architectural design to be proactive while fulfilling all the above-mentioned goals, promoting more than just maintenance or a technological update, adopting an inventive approach able to stimulate profound rethinking of existing conditions and impact the quality of the urban environment and building image.

INVENTIVE RENOVATION: TWO PROJECTS GENERATED BY DESIGN COMPETITIONS

Italian public housing agencies mainly award design assignments through procedures in which the role of architectural quality is marginal or absent, such as tenders or integrated contracts, or by managing the design phases internally through their engineering departments.19 By contrast, the WOBI-IPES philosophy leads to the selection of projects and professionals through architectural competitions with undoubted advantages in raising the average quality of the results, although these are complex and time-consuming procedures. Generally reserved for the design of new buildings, this thinking was extended to renovation projects – reductively defined as “energy upgrading with super elevation” tasks in the bid – at the time of the SINFONIA experience. By doing so, the new aspect introduced implies a cultural shift in design culture by attributing to renovation the same dignity and inventive approach usually assigned only to the design of purely new interventions. This took place in a context made particularly favorable by a specific regulation issued by the Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano to support institutions in launching competitions.

Indeed, the local government has approved a guideline document to support quality processes as a prerequisite for better design outcomes. The guidelines 20 give a wide range of instructions which include, for instance, careful preparation of specifications and related documentation; procedures structured in consecutive steps; remuneration for the winner; selection of the judging panel – notoriously one of the most delicate points in competition procedures since the panel and its composition contribute to the quality of the outcome to the point that a poor selection may affect the entire result. All five SINFONIA actions on public housing buildings in Bolzano came out of different design competitions – promoted according to a “restricted procedure” that implied an initial selection based on participant curriculum. Two of the actions – on which this text focuses – were designed by the same firm: AREA Architetti, founded by architects Roberto Pauro and Andrea Fregoni, based in Bolzano. Both projects interpret the task of “energy upgrading” in the most inventive ways, demonstrating a design ability to overlap new ideas onto existing buildings, leading to a profound aesthetic rethinking that changed their appearance. The two paragraphs that follow provide a detailed description of the projects. The texts are supported by photos and original drawings, general and detailed, from the designers’ digital archives. Besides enabling a full understanding of the architectural choices described in the text, the publication of these images aims to offer an operative contribution to the practice, making the solutions that were implemented accessible to technicians and scholars.

VIA SIMILAUN

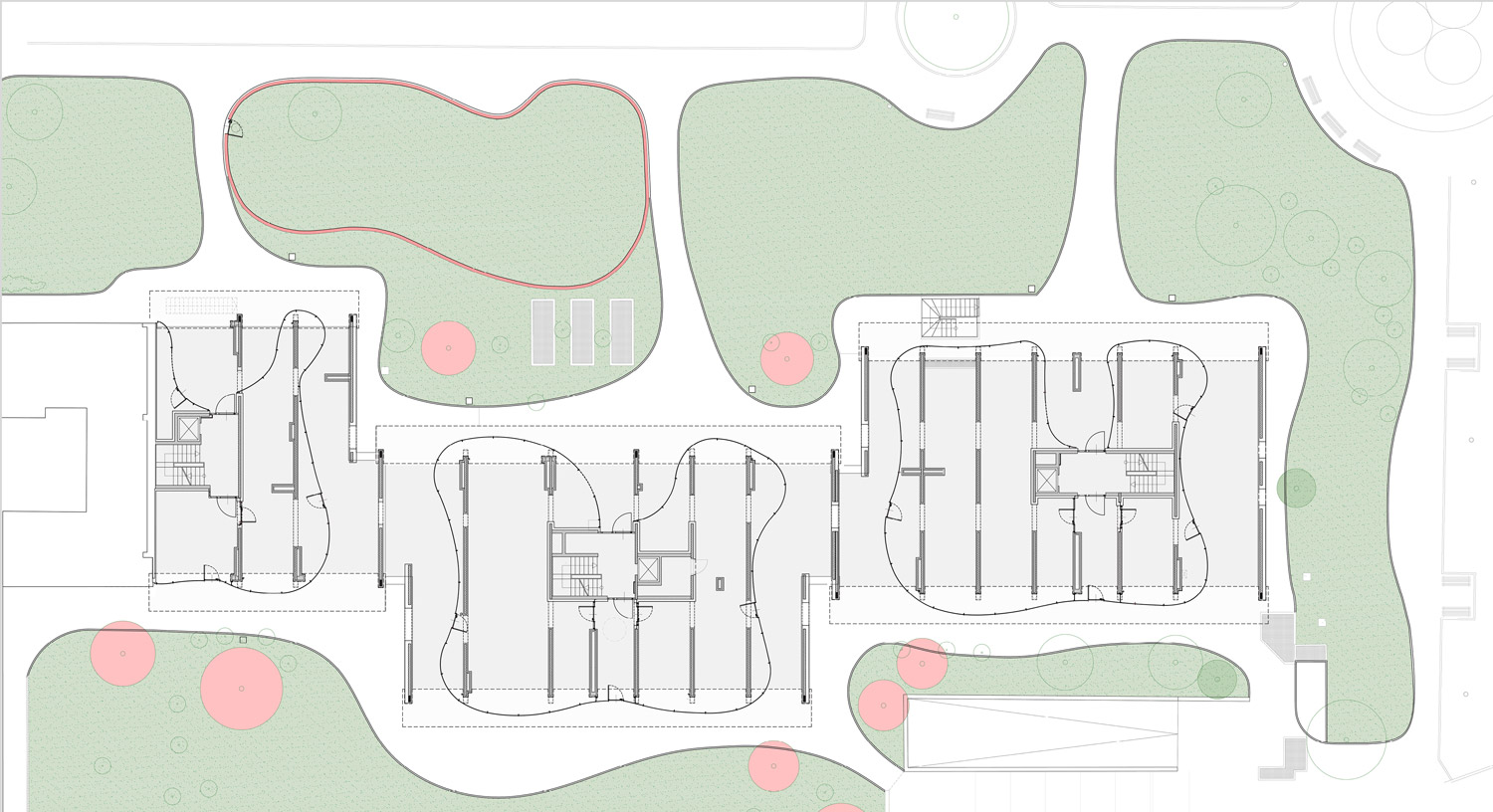

The Via Similaun 21 complex was built in 1978 and is part of a densely urbanized setting at the lower end of the Don Bosco district, in Bolzano’s southwestern outskirts. Although unrelated to the intervention, the proximity to the Casanova eco-district is emblematic. The latter is a leading example of European social housing experimenting with high energy performance – Class A requirements set by the ClimateHouse Agency 22 – combined with outstanding spatial and architectural quality. Unrelated but probably not accidental, the Casanova district is the result of a municipal action developed in the early 2000s with WOBI-IPES contribution, where masterplan and buildings were generated by the results of architectural competitions. The newly renovated Similaun building has fifty-nine dwellings and is barycenter to a large, pedestrian lot characterized by open-plan morphology defined by parallel buildings. The intermediate open spaces belong to each condominium, except for the central area, which is a linear public garden, with trees, paths, and leisure spaces. The volume is articulated as three contiguous but unaligned blocks and defines the eastern side of this public space, connecting its extremities: a sports area with a playground to the north, and a small square on the south – Piazzetta Anna Frank.

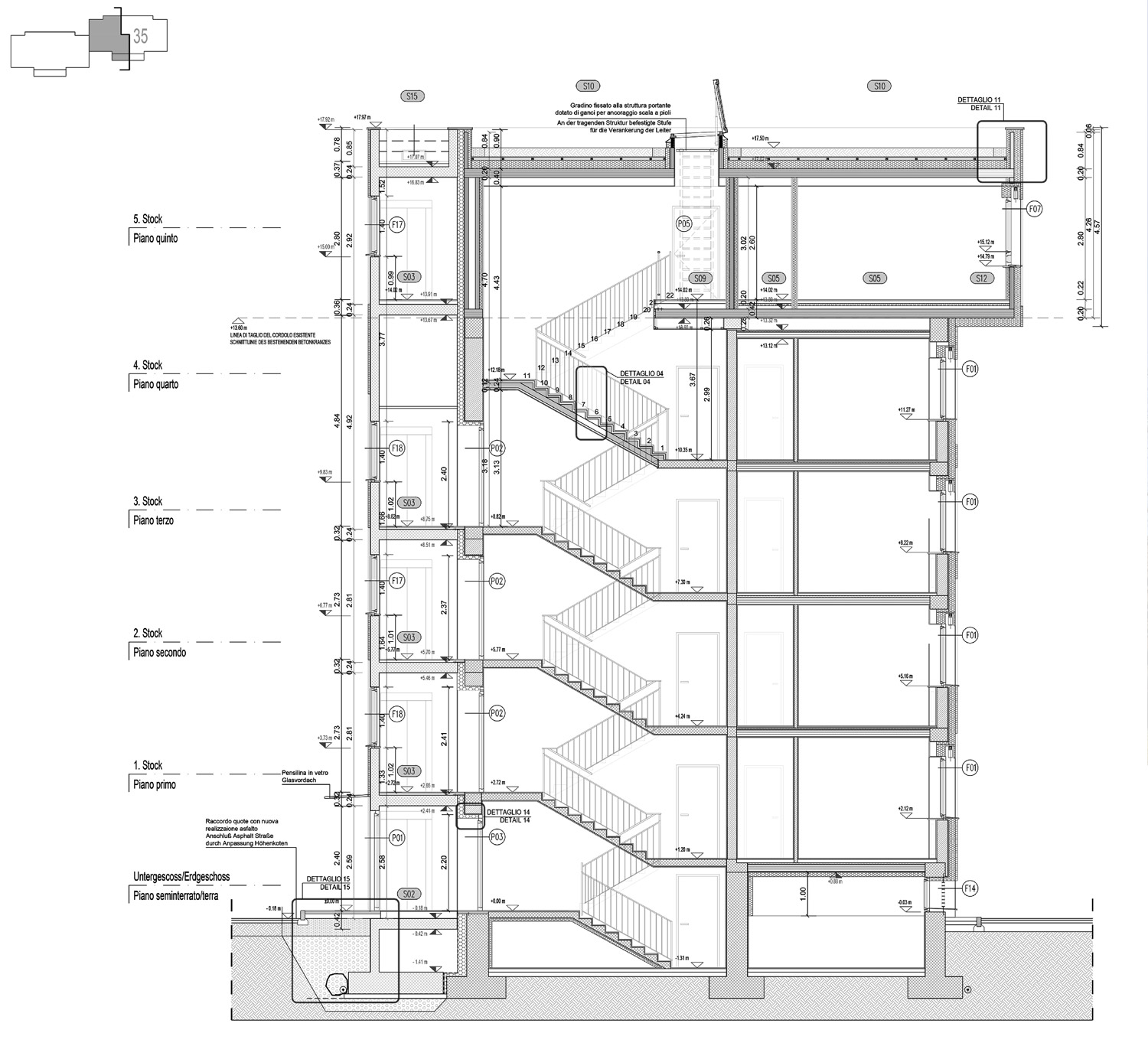

The building is supported by load-bearing reinforced concrete walls cast in situ, perpendicular to the façade arranged in a modular sequence which reflects two different dimensions. The load-bearing wall sides emerge perpendicular along the external envelope to support the continuous balconies on the main façades, originally characterized by concrete balustrades defining a series of linear planters. The continuity of horizontal and vertical structural elements between exterior and interior multiplies thermal bridges and is one of the main challenges the renovation project must address. The project was implemented without moving tenants out. Its aim was to reach the energy target while enhancing the existing building’s aesthetics, defining a coherent overlay inserted in its original textures, understanding its structure, and never contradicting its nature. A sub-module is recognized in the horizontal and vertical weave allowing a new regular grid to be established that can encompass all the irregular extant modules as a minimum common denominator, defining the base for a renewed architectural image.

The new plaster and metal façade is now totally white, as if to recall the Modernist character of the building. The primary intervention consists of preventing thermal bridges by covering the entire envelope – façades, floors, and ceilings – with an insulation rock wool layer finished in white plaster. This is in line with the exterior doors and windows being replaced with thermal-cut fixtures. The added layer geometrically aligns the extremities of all floors and bearing walls along the same outer vertical plane, so that the new metal grid façade can be installed on a coplanar structure. The metal frame serves, in turn, to anchor all elements composing the new façade, such as railings, panels, planters, and roller blinds.

Railings comprise a row of white metal tubes arranged horizontally and placed in the foreground against a perforated background panel. Planters provide each dwelling with a small green balcony corner, well integrated into the overall architectural concept. Their position along the façade is irregular, so as to increase the dynamic composition of the façade. Roller blinds run coplanar to the façade, ensuring a completely impervious result when lowered.

The set of elements mentioned above defines a three-dimensional membrane protecting the linear balconies, which can be regulated according to each resident’s need for protection from heat and light and need for privacy. The added frame defines the cresting of the building, raised by an extra floor, which enhances the vertical proportions while stopping plants positioned on the roof being seen from the public space. What has been described so far is not just the aesthetic aspect of an energy-saving intervention. The aim is rather to preserve and enhance the quality of each dwelling’s outdoor space: best use of balconies might actually have been reduced if 20 cm [7.87 in.] of thermal insulation had been added to the envelope. Taking out the current concrete planters and veneers and placing the new façade on the outer edge of the existing slab made it possible to recover lost space.

A second – equally important – design issue is the rethinking of the ground floor and its relationship with the open space. The positive role played by the building within its urban context is ultimately part of the design strategy. The building left spaces at urban level empty, permeable yet dark, and with no attributed function, resulting in an unpleasant sensation of perceived danger when crossing the ground level. The decision favored strengthening permeability in order to improve security, wagering on the opposite strategy to fencing. To do so, the layout of the front public garden was modified, creating paths that would come into direct contact with the building, making the link between the ground floor and open space fluid.

The new paths underneath the building are now coplanar and uniform to the exterior ones, using a continuous surface of washed concrete. In addition, a better hierarchy has been established: while crosswalks are strengthened, some areas are closed off and reserved for the building. Indeed, three organic volumes define common spaces used to store bicycles and strollers. Each volume is differentiated by color and shape; and the walls have been designed with the installation of a lightweight metal structure in micro-perforated aluminum panels. The transparency provided by the perforation allows what is happening on the other side to be seen, contributing to safety. For the same reason, night lighting is also essential in crossing areas.

The intervention acts in parallel at plant engineering level: the existing centralized heating system, which did not monitor individual consumption, has been modified to introduce a metering system. The project also involved modification of the existing thermal power plant, replacing the six gas-fired boilers with a sub-district heating plant connected to the district grid. The methane gas network was deactivated, and kitchens have been fitted with electric ovens and hobs. Solar thermal and photovoltaic panels have been installed on the roof, meeting domestic hot water needs in summer and contributing to district heating in winter.

VIA ASLAGO

Via Aslago 23 is located on Bolzano’s southeast side. The entire district morphology appears as an open-plan plot, where a group of linear apartment blocks creates a neat landscape. The residual open space is partly fenced, mainly paved, and allows for vehicle traffic, parking, and pedestrian access to individual buildings. The overall architectural quality is quite ordinary, even mundane, repeating a few building types with minimal floorplan, volume, or color variations, without striking features worth preserving. Although not memorable, the complex has a rather domestic feel with its pitched roofs, pastel façades and (mostly) exterior shutters.

The six buildings involved in the renovation (numbers 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35) house a total of seventy dwellings and date back to 1961 – except for number 27, built ten years earlier. They were originally four stories high, rising from a mezzanine above the semi-basement cellars. Except for the older building, they replicate the same type – occasionally mirrored – with the same features: concrete structure with perimeter walls in brick and stone; three dwellings per floor in a symmetrical layout; a central minimal stairwell, no lift; a light pink plaster façade with a repetitive window arrangement reflecting the typical floor layout and without balconies. This being the premise, the intervention tackled energy upgrading requirements and raised an extra floor to change the overall appearance radically by acting on façade composition and volume layout.

The new architectural image is characterized primarily by a skin that overlaps equally both the existing body and the added volumes. This new surface includes the introduction of a necessary exterior insulation layer, refined with plaster. It is patterned with dark-colored rectangular carvings, slightly set back along the light gray surface. Each rectangle is randomly positioned around the existing openings to make them look more extensive and varied on a frontage that becomes dynamic by detaching from the standard plan. This three-dimensional effect is made possible through slight variations in the insulation thickness, and through chromatic differences combined with variations in plaster grain. Within this new composition, all windows and doors were replaced, but with the same size fixture to avoid impacting the interior spaces and reducing inconvenience for tenants during installation. For windows, the aesthetic variation was limited to the proportions of single sashes, which now have larger sash and asymmetrical divisions, with external dark-colored sliding flat slats, which fold in their insulated casings.

Cadenced volumes further support architectural transformation thanks to localized façade thickening and super elevation. The façade thickening is located beside each distribution core, allowing for the installation of new lifts and landings for all stairwell mezzanines. This addition was implemented with an external and statically autonomous reinforced concrete structure, properly anchored to the building and clad with the same façade pattern. These volumes also include new balconies on both sides of the lifts, directly connected to two of the three dwellings on each existing floor. The super elevation comprises a total of fourteen extra units on the top floor of five of the six buildings, using innovative timber construction technologies (number 27 was not raised for static reasons). After demolishing the existing concrete and brick structure, and cutting the perimeter curb, an X-lam separating structure was positioned on the top of the building, holding new walls and floors.

The added dwellings follow a different layout from the lower ones. The new volumes – in part coplanar to the extant, in part projecting beyond the façade line, in part set back to define balconies – redesign the top of the buildings, breaking up symmetry and overcoming the previous static image. The renovation led to a massive reduction in energy consumption, which fell below 25%. The new façade and roof insulation interventions were completed by a pellet system producing energy for heating and domestic hot water (DHW), which contributed to energy saving, lowering CO2 emissions, and the use of renewable and locally available sources. Moreover, indoor comfort is enhanced through a decentralized mechanical ventilation system installed in the perimeter wall of each apartment, allowing air exchange in the apartments and recovery of heat from expelled air.

CONCLUSIONS

The described projects, in all their diversity, can be seen as pioneers in the debate on how to intervene in Italian public housing heritage through regeneration actions that combine a reduction of environmental impact with architectural rethinking. Several lessons can be learned – in keeping with the SINFONIA project’s mission to share results 24 – not only from the relevant architectural outcomes, but also by expanding on the process through which these outcomes were achieved. The final paragraphs sum up with a few concluding remarks: the first, about design approach, emerges from a synthetic comparison between the two interventions. The second, concerning the process, addresses the crucial role played in the way the design tasks are assigned.

Via Similaun and Via Aslago: Different Outcome, Same Attitude to Contemporary Design

Despite being by the same firm, a swift glance at compositional choices and the relationship with the preexisting buildings indicates that the two interventions appear to have extremely different design outcomes. The first, located in Via Similaun, focuses on the thickness of the façade, giving a new design to the existing balconies that reinterpret, not delete, the Modernist identity. On the contrary, the renovation of the Via Aslago buildings can be defined as a complete metamorphosis, which strongly impacts the former architectural image by overwriting existing façades with a layer of purely contemporary language. Moreover, the first action remodels the ground floor, improving its relationship with its surroundings, while the second does not address this issue, instead concentrating on the roof, adding new flats in an extra volume. However, both actions share a creative approach that brings them out of their anonymity, rendering them more recognizable, more authorial architectures, perhaps at the price of losing some of their own domestic reassurance – at least in the case of Via Aslago.

Envelope Image and Energy Upgrading

The projects offer two possible alternatives for rethinking the appearance of many ordinary buildings lacking in architectural value while implementing energy upgrading. The façade, probably the most identifiable part of a structure, is notoriously the main cause of energy-consuming behavior. Intervention on it is rather inevitable and raises the issue of the building image, which cannot withstand the addition of a continuous layer of insulation as if nothing had happened. Two options are available: the former resorts as far as possible to a mimetic intervention, limiting differences from the original and giving the designer a predominantly technical role. The latter, which we see in Bolzano, acts in a reinterpretative key, transforming a refurbishment into an architectural opportunity. Inventive skills prove essential, especially when seeking an architectural image update (or change) that public housing contexts often require. It is equally essential to improve, or at least not diminish, the quality of inhabited spaces, as is the case in Via Aslago, thanks to the addition of balconies on the two sides of the new lift, or in Via Similaun by relocating the railings toward the outside perimeter of the existing balconies, so as to recover the thickness lost with the addition of thermal insulation.

Design with Constraints

Both projects highlight the importance of being able to implement design solutions in highly constrained conditions. Typical budget constraints inherent to public housing led to design limitations generated by energy-saving goals overlapping with the need to develop technical solutions that can be put in place without moving tenants out of their homes during construction work. Both interventions speak of the need to overcome architectural design difficulties so as to adapt to extremely controlled conditions, seeking space and opportunities instead of falling back on outcomes that prefer a problem-solving quantitative approach to a quality solution.

Missing Issues

Although they are presented here as good practices, neither example covers all aspects and themes of public housing renovation. For instance, they do not experiment with housing types or introduce functions or uses other than the extant. They take no action against typological seriality, nor do they address the issue of new housing needs linked to the changing structure of households or variable home–work link. And they do not tackle the issue of functional mixité [diversity] by accommodation other than housing. However, they probably do represent the first significant results in Italy that are on a par with some of the best projects we are used to seeing around Europe, reaping the benefits of being in a border area with important influences on architectural culture.

The Architecture Competition as a Tool for Promoting Design Quality

In Italy, design assignments for public construction works above a certain financial limit are required by law to be awarded by public tender. This is only rarely achieved by means of an architectural competition. Instead, it is more common to assign the contract through tenders to subjects ranked on the basis of certain access criteria, a technical offer – including a methodological report explaining how the tenderer intends to carry out the service and listing a selection of similar works previously completed – and a financial offer where the lowest wins. Bidder evaluation, generally carried out by the contracting authority’s in-house experts, is necessarily based on performance criteria, objectively measurable, thus encouraging an exclusive interpretation of architecture as a technical service, while neglecting aspects related to design quality. Instead, the role of procedures that give greater centrality to design outcomes must be relaunched. Architecture competitions are certainly one of the most reliable alternatives as they allow the best proposals to be selected from those submitted. Despite their long duration, complex organization, and unpredictable outcomes, they are one of the few options available for improving the quality of design. However, successful design competitions require a certain level of caution to avoid damaging efforts.

A crucial element is to entrust the proposal evaluation to a qualified panel, possibly including professionals and experts distinguished in the fields relevant to the call, combining local context experts with representative members who are up to speed on the contemporary architectural debate referable to the competition. Transparency in the evaluation process is also a step that needs to be strengthened, for example by establishing an open digital archive of the results making them accessible to the public, and displaying the work of all participants, also with a view to stimulating an open debate. The panel members must understand in advance the actual feasibility of the projects examined without giving in to superficial allure that would put a great distance between what is chosen and what is realized. A good panel evaluates drawings and images with development, construction, and future maintenance stages in mind. Compliance between what was simulated – in drawings and renderings – and the actual result is also an example of a successful choice.

The Bolzano cases described above show significant coherence between the renderings through which AREA Architetti won the commission and the photos after realization – this also demonstrates the credibility of the designers in using the graphic representation as reliable anticipation and not misleading communication aimed at winning the favors of a judging panel. This paper is certainly not the place to examine all the recommendations that should be applied to design competitions, but rather for reiterating the importance of this tool, which should be extended not only to all new public buildings but also to renovation projects. This should be ensured by a national law for architecture, which has been under discussion for over thirty years, and whose absence is increasingly problematic.25 Experimenting, introducing, or multiplying these opportunities would allow Italy’s currently struggling architectural culture to develop its skills through tangible experience.

Several studies on this subject have been developed over the last twenty years. Among them, two academic journals significantly contributed to the debate by publishing two special issues: Dash Delft Architectural Studies on Housing 14 – From Dwelling to Dwelling: Radical Housing Transformation (Rotterdam: Nai010 publishers, 2018). ZARCH: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Architecture and Urbanism 5 – El legato de la vivienda masiva moderna (2015).

Italian architecture’s withdrawal from the contemporary housing debate can be proved by considering the very few projects published in the last twenty years in the most renowned books on collective housing (e.g., the “density” series published by a+t or other books published by Actar or Birkhäuser well known to housing researchers and practitioners). Another proof: the Baffa-Rivolta European Social Housing award, promoted by Milan Chamber of Architects, has never been awarded an Italian project in fifteen years – http://premiobaffarivolta.ordinearchitetti.mi.it. There are a few exceptions, such as the two editions of the “Abitare a Milano” design competition launched by the City of Milan in 2005. Nicola Braghieri, “Milano: i concorsi e l’architettura sociale,” Casabella 789, (May 2010): 74–77.

Fabio Lepratto, “Housing Bricolage, Tools for Manipulating the Post-war Collective Housing,” in Dash Delft Architectural Studies on Housing 14 – From Dwelling to Dwelling: Radical Housing Transformation (Rotterdam: Nai010 publishers, 2018): 14–32. Available at https://journals.open.tudelft.nl/dash/article/view/5062.

Federcasa, L’edilizia residenziale pubblica. Elemento centrale della risposta al disagio abitativo e all’abitazione sociale (Roma: Sintesi delle proposte Federcasa, n.p., 2015). Nomisma, Federcasa, Dimensione e caratteristiche del disagio abitativo in Italia e ruolo delle aziende per la casa (Roma: Sintesi, 2016).

“Banlieues 89” is an association created in 1981 under the direction of architect Roland Castro and urban planner Michel Cantal-Dupart. The goal was to improve the quality of the suburbs in France through innovative urban and architectural projects.

Fréderic Druot, Anne Lacaton, and Jean-Philippe Vassal, Plus (Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2007).

Regulated by Article 119 of Decree-Law No. 34/2020 (“Rilancio” decree). Initiative valid from July 1, 2020 for a limited time.

Regulated by Law No. 160/2019 (Art. 437 ff.).

In coherence with Mission 2 (Green Revolution and Ecological Transition) and Component 3 (Energy Efficiency and Building Renewal) of the PNRR.

For PINQuA only, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Sustainable Mobility issued a dossier presenting the first project results on April 13, 2022. Available at: https://www.mit.gov.it/nfsmitgov/files/media/notizia/2022-06/Report%20PI....

In cooperation with Luca Talluri (Federcasa president from 2014 to 2020) and Alessandro Almadori (Federcasa Lab).

The ongoing initiative, named “Luoghi in attesa di progetti” and coordinated by the author in cooperation with Massimo Bricocoli and Stefano Guidarini (DAStU - Politecnico di Milano), includes training seminars and involvement of public housing agencies in research-by-design and teaching activities at Politecnico di Milano’s School of Architecture Urban Planning Construction Engineering.

The information in this essay is partly based on a presentation given by engineer Gianfranco Minotti (WOBI-IPES) and architects Roberto Pauro and Andrea Fregoni (AREA Architetti) at the seminar “Tor Bella Assai! Riflessioni sulla rigenerazione dei quartieri pubblici a partire da un progetto per Tor Bella Monaca” held on January 12, 2021 at the Politecnico di Milano.

Fabio Lepratto, Trasformare case e quartieri (Santarcangelo di Romagna, It.: Maggioli, 2021).

Francis Rambert, Martine Colombet and Christine Carboni, Un bâtiment, combien de vies?: la transformation comme acte de création (Milan: Silvana, 2015).

The information in this essay makes extensive use of direct sources through interviews with actors involved in the processes, carried out with the support of Federcasa, and addressed directly to some of the actors involved in the SINFONIA project.

These insights were presented by engineer Gianfranco Minotti (WOBI-IPES) at the above-mentioned seminar held on January 12, 2021 at the Politecnico di Milano, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies.

This information is derived from interviews the author conducted with technicians and managers of Italian public housing agencies as part of a university collaboration with Federcasa (the National Association of Italian Social Housing Agencies).

Guidelines on urban planning, architecture, and engineering competitions, issued under Article 40 of Provincial Law 16/2015 “Dispositions on public procurement” –

www.ausschreibungen-suedtirol.it/pleiade/comune/bolzano/documenti/Link_0....

This paragraph was completed thanks to information collected from a presentation by architect Andrea Fregoni (co-founder and partner of AREA Architetti) held on January 12, 2021, at the Politecnico di Milano, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies.

CasaClima Agency is a public and independent certification agency providing evidence of buildings’ energy performance, sustainability, and quality, in line with the European Parliament Directive (2010/31/EU) – www.agenziacasaclima.it.

This paragraph was completed thanks to information collected from a presentation by architect Roberto Pauro (co-founder and partner of AREA Architetti) held on January 12, 2021, at the Politecnico di Milano, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies.

The transferability and scalability of the solutions implemented were considered essential outcomes of the project. SINFONIA cities – including “early adopter” Seville (ES), La Rochelle (FR), Rosenheim (DE), Borås (SV), and Paphos (CY) – are indeed sharing their experience through the “Replication Cluster,” a joint initiative with a simultaneous project called EU-GUGLE (www.eu-gugle.eu). This network aims to share cumulative experiences through peer-to-peer support offered to other cities and communities interested in implementing similar district-scale refurbishment strategies.

For the ongoing debate on a law for architecture, we refer to the initiative put in place by MAXXI – National Museum of 21st Century Arts to reopen the discussion. The website sums up progress since 1994 – www.versounaleggeperlarchitettura.it.

Figures 1, 4, 5, 7-9, 12, 13: © AREA Architetti Associati.

Figure 2: Images © 2022 Google; images © 2022 CNES / Airbus, Maxar Technologies, cartographic data © 2022

Figures 3, 10, 14: © AREA Architetti Associati and Andrea Zanchi.

Figures 6, 11, 15: © Andrea Zanchi.

Fabio Lepratto studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano and at the Delft University of Technology, from where he obtained his Ph.D. in 2017. His research thesis dealt with the contemporary transformation of post-war mass housing. After a three-year research grant at the Department of Architecture and Urban Studies, he is currently a researcher and lecturer in Architecture and Urban Design at the same university. Since 2010 he has been involved as a freelancer or consultant in various housing and urban design projects in Milan.

E-mail: fabio.lepratto@polimi.it